All images by Edoardo Liotta for Rice Media

Growing up, I remember a period in which my mum temporarily collected Barbies. She started with an array of nondescript dolls—beach Barbie, athlete Barbie, and a few celebrity dolls. But her most prized collection was the Dolls of The World series. Tucked away in a drawer away from children’s reach—these were for collectors only—was a Barbie in a kimono, a Native American donned with feathers, a Russian in her traditional poneva, and… a Singapore Airline Girl.

At the time, I thought little of it. While the SIA Barbie was not created as a part of the Dolls of the World collection, it only made sense to collect her as a part of it. The SIA girl was, after all, seen as a Singaporean icon internationally.

Now, decades later, it doesn’t sit as well in my memories. I wonder why Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines all got national dolls made by Mattel, while Singapore only got one for its national airline.

To find out how the SIA doll became the unofficial Singapore Barbie, I spoke to Asia’s biggest Barbie collector, who tells me it’s rooted in the nation-building of a post-independent Singapore.

The birth of the Singapore Girl

In 1972, Malaysia-Singapore Airlines transitioned into being known solely as Singapore Airlines—an expected move with the country’s newfound independence.

From the outset, Singapore Airlines was faced with a particular challenge. Without domestic routes to serve, it had to compete with other airlines for an international customer base.

At the time, many airline marketing campaigns advertised the idea that customers would get a slice of the source country onboard.

“Have you ever done it the French way?” a French Airlines advertisement asked, above an illustration of a couple enjoying Champagne, the country’s celebrated beverage.

American Airlines posters featured the Manhattan skyline and the Golden Gate bridge. A Geisha for Japan Airlines, the Amalfi Coast for Alitalia, the Alps for Swiss Air, a golden beach for Qantas.

But what icon would Singapore Airlines proudly exhibit? What slice of Singapore would travellers get onboard SQ?

The Singapore Girl Barbie

Since SIA was established in 1972, it has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the Singapore Girl advertising campaign alone —100 million of which were spent in 1993 (the year the third SIA doll was released, but we’ll get to that later).

Batey Advertising, the agency infamous for being entrusted with the Singapore Airlines account for decades, crafted the Singapore Girl. And within the first few years of the Singapore Girl marketing campaign’s launch in the 70s, the first SIA doll was made.

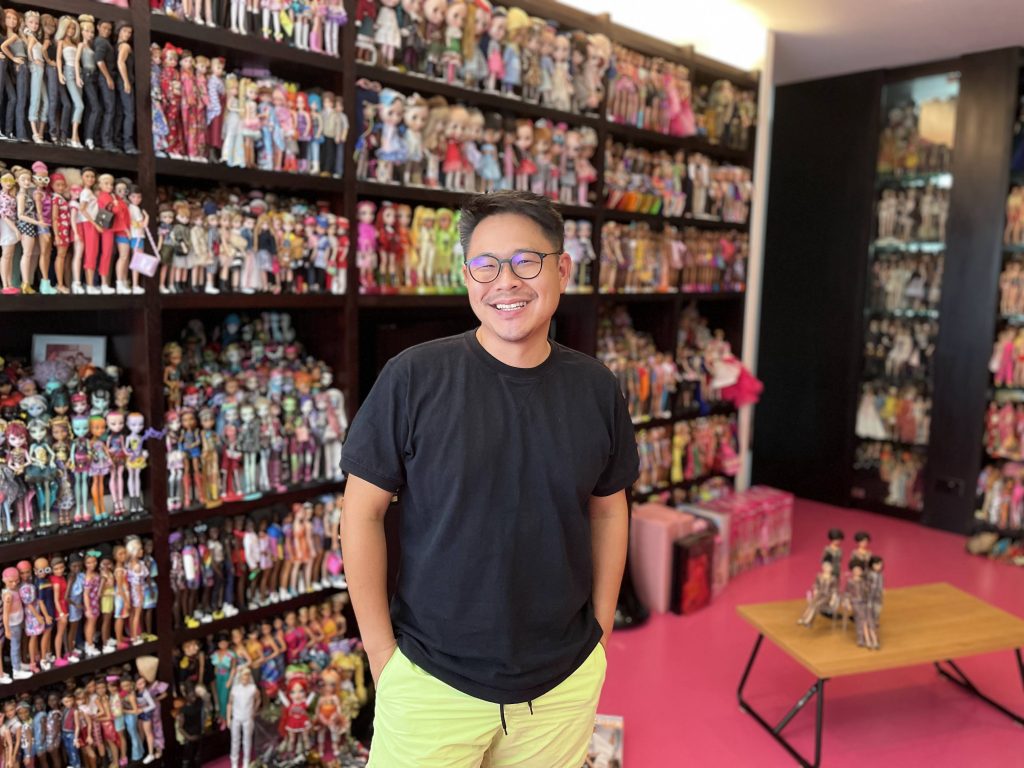

“I found the first 1970s SIA doll in an antique shop,” said 42-year-old Jian Yang, the world’s second-largest Barbie collector. “I have googled, I have asked around, and no one knows anything about her.”

Jian suspects that beyond existing as a marketing tool for SIA alone, the Singapore Girl was fabricated to market Singapore as a hub in general.

“Singapore is one of those countries where our history isn’t long enough, unlike Europe. Since independence, we’ve been trying to create an image for ourselves that erases pre-independence times,” he explained.

“To this day, I think we struggle to identify what is so unique about Singapore. That is why for a while, our tagline was ‘Uniquely Singapore.’ It’s like we couldn’t find what to say about our own country, so we just went generic and called it unique.”

“The SIA doll, as an extension of the Singapore girl, was trying to make an icon for the country.”

What other countries use their airline as a national symbol is a question both Jian and I pondered. You’ve never heard of the Qantas Girl or the Pan-Am Girl—likely because these countries never had to use these.

Diversity and… inclusion?

About 20 years after the first SIA doll in the 1970s, Mattel acquired the license to make the Singapore Girl into a Barbie in 1991.

“She was fucking hideous,” Jian yelled as he pulled the Barbie out of a box. “At the time, there were very few Asian barbies in the first place. So they tried to further Asianize the face of the original Asian Barbie.”

Jian confessed that he always found the first SIA Barbie dull in colour, on top of having features he found borderline problematic. According to Jian, the 1993 revamped and improved version of the SIA Barbie was at least more vivacious.

The Singapore Girl wasn’t the first Asian Barbie to exist—in 1981, Mattel released an “oriental Barbie” alongside the Hispanic and Black Barbie. She was, however, the first Barbie in Mattel’s history to have her head pushed into her neck.

“At the time, they must have thought that the original long neck was unnatural or non-Asian,” he explained.

Like the hyper Asian features of the Barbie doll, the Singapore Girl image has long been criticized for reinforcing sexist stereotypes of the subservient Asian woman.

Ironically, however, the success of the Singapore Girl also helped push boundaries for Asian representation in the West. In 1993, she was added to Madame Tussaud’s waxworks museum in London. Before her, only six other Asian figures were featured in the museum. Only one of these—Benazir Bhutto, a former prime minister of Pakistan—was still active as a personality at the time.

On the global front, the Singapore Girl was a hit—she was featured in the New York Times, made it to museums, and was blasted in advertisements across the globe.

But domestically, whether the Singapore Girl did much for representation is a different question entirely. She was, for instance depicted as Chinese when Singapore has three majority races.

But realistically, could she have been crafted any better?

“Even as a Singaporean and Barbie collector, if you asked me what a Singaporean Barbie should look like, I wouldn’t know what to tell you,” Jian sighed. “What should she wear? A kebaya? That’s a Malaysian thing. Cheongsam’s are Chinese. Sari’s are Indian.”

“If you really want to make a local doll, she would have to wear a Love Bonito outfit in shorts and slippers.”

Maybe, just maybe, the Chinese girl in a Malay kebaya was the best presentation of the Singapore identity given the time.

How far have we come now?

50 years later, Singapore has made a name for itself far beyond the Singapore Girl. But Jian still finds the Singapore advertising campaign a struggling pursuit.

“On one hand, there is what the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) pushes—the Merlion, Marina Bay Sands, the Night Safari, and so on,” he said. “This is largely targeted at foreigners.”

“Then, there is the agenda of ‘local made,’ which is pushed to both foreigners and locals. We have a launchpad at Biopolis where SMEs are encouraged to develop Singapore-first products and solutions. Then there’s Design Orchard for local design. But how many locals have you seen actively shopping there?”

Design Orchard, in itself, illuminates the dilemma, according to Jian. “There are so many Batik shirts for men, but Batik is not our thing. It’s Indonesian or Malaysian, and it’s been imported.”

“That is our issue. Our culture is appropriated from the four races—of which one is literally called ‘other.’ So, it’s hard to say what ‘Singaporean’ is.”

Since independence, Jian and I discussed how Singapore has been so focused on putting the majority three races into boxes that it has disincentivized the evolution of a single Singaporean culture. That’s why the Singapore Girl Barbie had to have a hyper Chinese face and wear a hyper Malay outfit—it features both cultures, but it doesn’t display what happens when those cultures mix.

“I hate that we’re having this conversation over a doll,” Jian laughed. “Because Barbie is an American icon. So why did we, Singapore, try to further our icon using an American icon?”

“You could argue that they are leveraging an American icon to create a Singaporean one,” I responded.

Now, SIA has moved on from Barbie, who has passed her prime in the 90s and early 2000s. In 1999, when Jian was helping with Mattel’s PR, he saw a green kebaya Singapore Girl Barbie. She never got released to the public, but he still has her prototype at home. Eventually, they released ‘Kristie,’ a non-branded green Kebaya SIA doll a few years later.

Now, instead of a Barbie, there’s a Funko POP SIA girl and an SIA Precious Moments girl. Evidently, toys are still working in furthering the Singapore Girl image.

Looking back at the short-lived SIA Barbie, Jian maintains that she must have been a commercial success.

“The businessman traveller is always going to need a last-minute gift to buy on board to bring to his kids,” Jian proclaimed.

But the contribution she made to the Singapore identity remains indefinable.

“I only realised Singapore had a brand name and uniqueness when I moved to the Middle East from 2007 to 2011. We were known as hard-workers, pclever, and a country that developed fast. We were a shining example.”

I would argue that the Singapore Girl represents that. But to Jian, she just represents how Singaporeans “are all struggling but taught to maintain poise and composure.”