RICE is the official media partner of Singapore International Film Festival 2019.

Popular narratives about sexual violence tend to neglect the problems with our institutions for reporting and justice. These are the narratives we read in mainstream news, which are then reproduced in our culture, shaping how we understand violence as a society.

For instance, we hear about a few bad eggs—troubled, confused individuals who are reported and duly punished. We learn that they are contrite. Their victims will get therapy and recover soon enough.

In reality, the processes by which perpetrators are brought to justice is never linear or straightforward. Breaking the silence has its costs, and survivors are always having to ask themselves if it was worth it.

In Singapore, we’ve heard many stories from survivors that have been met with backlash, skepticism, victim-blaming, and inaction. People who report sexual assault or rape to the police may be asked to take a lie detector test, which can cause more trauma for survivors, despite the fact that polygraph test results are not admissible evidence in court. Even after NUS set out to review its sexual misconduct policies, it will not re-open past cases, including that of Monica Baey. Sharan V Kaur highlighted on a Twitter thread that the annual number of reported sexual assault cases has increased, from 180 in 2011-2013 to 250 in 2014-2018. About half of these cases were met with inaction because no offence was found.

Ultimately, the structures in place to protect us have tried to silence, appease, and justify themselves. While perpetrators have been named and shamed in mainstream news media, we need to question: to what end?

Then-PM Lee said that Singapore’s culture was based on a “Chinese-based Confucianist culture of dominance” where women had a defined role.

A few examples of how this manifests: men are still not expected to do domestic work; male policymakers still get to make decisions about female autonomy; and male perpetrators of sexual violence can have their dignity and future prospects protected. When men who experience sexual assault are doubted and shamed, that’s also a result of a patriarchal society where we assume men can never be victims.

One popular belief is that we can resolve this patriarchy by aiming for equality. And by “equality”, we usually mean that women get all the same opportunities as men, such as workplace promotion and political representation. This is important, but it is ultimately pointless if we don’t also acknowledge and address how women are still expected to have successful careers that they must then sacrifice by leaving the workforce early to become mothers and caretakers. Ever since women started to enter the workforce in the 1970s, we have been treated as a flexible pool of labour for the economy; in 1983, Lee Kuan Yew made a National Day Rally speech that rebuked female university graduates for causing Singapore’s declining birth rate.

Because this pressure is not unique to Singaporean women, art and media representations of female liberation can be powerful because they give us the space to think beyond strict ‘equality’ as the end goal.

“We don’t have another choice.”

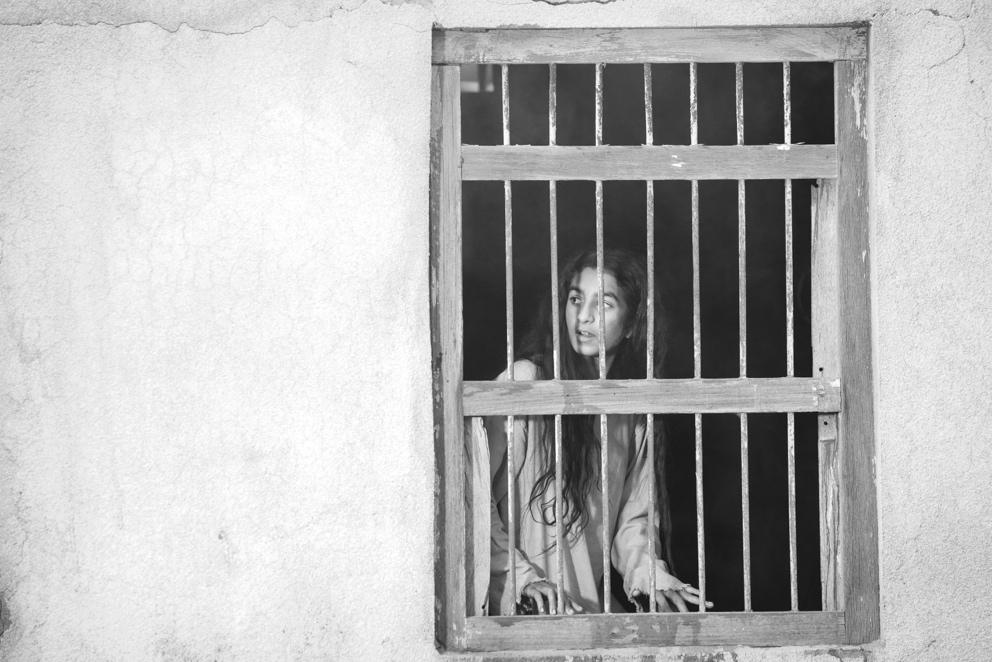

The village in the film can be read as an extreme analogy for a patriarchal society that survives through a perverse ritual (no spoilers). The village women are always cloistered indoors, and serve only to make more babies while the men go out to sea.

Hayat, the film’s protagonist, survives the above mentioned ritual and is initiated among the men as a hunter. Yet she is bullied, abused, and overworked, further alienated by the women of her village. Shahad Ameen has spoken about the film as a personal story about expectations of women and girls in Saudi Arabia, but she chose to leave its setting ambiguous: “I wanted to tell a timeless story because it could happen anytime and, really, any place.”

Hayat eventually realises that liberation is not in taking up the man’s role in society. She rejects Amer’s argument that things have “always been this way.”

“Maybe there was another choice,” she says.

In Something Old, New, Borrowed, and Blue (dir. Mouly Surya), a mother gently and playfully instructs her daughter in how to serve her soon-to-be husband. In A Girl Missing (dir. Kōji Fukada), a nurse grows close to the family of her elderly patient, but this relationship inadvertently develops into a tragic incident for her patient’s granddaughter. Misunderstandings and betrayals result from the family’s silences around love, sexuality, and trauma; throughout the film, media sensationalism feeds on their tragedy and makes it near impossible for them to recover.

Let’s not forget that the people who are most vulnerable to sexual violence are also the ones with the least access to legal recourse or a public platform, a fact that these film narratives also emphasise. In Singapore, for instance, domestic workers are vulnerable to sexual harassment and abuse, but could have their passports impounded during investigation. LGBTQ individuals face a greater risk of sexual violence, but are less likely to report for fear of social and legal repercussions in Singapore (read: 377A).

In that same 1983 speech, then-PM Lee said that Singapore’s culture was based on a “Chinese-based Confucianist culture of dominance” where women had a defined role.

It’s a reminder from the past that even today, patriarchal cultures and institutions are the very foundation of Singapore society. Before things can change, we need to recognise this fact.

Recently, the alleged administrators of this Telegram group were arrested, but what about everyone else who was complicit? What about our friends and peers who might be in similar groups? How and why have reported cases of sexual assault and rape increased since 2014 (to say nothing of those that go unreported)?

I remember when rape seemed like a horror story, a nightmare used to scare us into good behaviour and conservative attire. Today, I am heartbroken, angry, and afraid, but no longer surprised. How have we, collectively, allowed this to happen?

Where institutions fail, social media offers one way to share one’s experiences and find community. AWARE runs a sexual assault responder training workshop that focuses on care and support for survivors, but the onus cannot rest on a few. Responsibility involves making sure those around us feel safe enough to share their experiences, and that every incident is taken seriously.

Things will never shift without us pushing against the status quo. And by this, I mean all of us holding one another accountable.

All Rice readers enjoy S$2 off the opening film and S$1 off all other titles with the promo code SGIFFxRICE.