But the people of New Zealand are more impressive than their mountains, a friend insists.

I am sceptical, because New Zealand has been on my bucket list precisely for her mountains, valleys, rivers, and lakes. As a teenager, I’d right-click and save dreamy Tumblr landscapes of the country, waiting for the day I finally got to go.

In some ways, I want to go because it is the furthest thing from my five-room HDB where I live with my mother and sister, separated from our neighbour’s unit by a distance of two metres and the vague promise of kampung spirit. Nowhere does the world feel smaller than in Singapore, where six degrees of separation shrink to three. I’ve grown up knowing only the cramped and crowded, and I want the vast open spaces of a country whose population in its largest city is a quarter of our little red dot’s. (At 1,086km2, Auckland boasts a population of about 1.4 million. In comparison, Singapore has approximately 5.8 million people, with a land size of 721.5km2.)

It is a fool’s errand to convince a Singaporean like me that they should visit New Zealand for her people, when people are mostly exactly why they’re escaping their own country. Describe the allure of mountains, however, and you have a winning sales pitch.

Mountains are immovable, unchanging, and majestic. Their mere outline is enough to render any city dweller slack-jawed, as they briefly entertain the dream of retiring on a farm in the New Zealand countryside.

A mountain’s immeasurable and tangible beauty lines the postcards in souvenir stores, overwhelms WhatsApp group chats as the signature of a sublime holiday adventure, and takes up a bulk of the 500-odd photos in the Facebook photo dump of any trigger-happy Singaporean returning from conventionally scenic countries. You can’t take a bad photo of a mountain, although it is just as impossible to accurately capture its grandeur.

People, in comparison, are painfully ordinary. If you’re lucky, a couple leave you with the same wide-eyed wonder from standing next to a cerulean lake that’s framed by an endless silhouette of the mountains. But expecting every person to surprise you as such is a recipe for disappointment.

Unlike mountains, it takes awhile to uncover the beauty of a country’s people. Even after you do, genuine connection and camaraderie aren’t instant. But unless you’re relocating or living in one place for an extended duration, you don’t have to love—or even like—the people of the place you’re visiting to enjoy your holiday. A tourist is a passer-by, not a permanent resident.

I don’t expect to fall in love with the people of New Zealand. But at the start of this year, I spend 14 days in the country and I am no longer the same.

Love for a partner, friends, or family is expected—but love for a complete stranger, whom you might never see again, is not something Singaporeans encounter or practise with seasoned regularity as the Kiwis do.

In their culture, this inclusive closeness manifests in whānau: the Māori-language word for extended family, often used to describe the style of hospitality that is apparently unique to New Zealand. Regardless of blood ties, everyone is treated like family, so there is no obvious distinction between someone’s cousin, friend, and one-hour-old acquaintance. To the Kiwis, whānau isn’t just a social currency that’s priceless, but also an intrinsic way of life.

In theory, the concept sounds awkward to my middle-class Singaporean Chinese upbringing. Growing up in a family who wasn’t expressive meant that family was associated with duty and obligation, not emotional intimacy. Even the oft-evangelised ‘kampung spirit’ (i.e. a sense of social cohesion in a community where there is understanding and compromise among neighbours) has always felt contrived, more aspirational rhetoric than actual culture.

The cynic in me naturally expects this from New Zealand’s whānau culture too.

But my three colleagues and I haven’t even set foot in the country when we’re already shown this grace by the staff onboard the Air New Zealand flight. They approach me with frequent “kia ora” greetings, engaging conversation, and even more care and concern. It might be standard protocol, but even so, I don’t feel like they’re purely going through the motions.

After all, where hospitality is concerned, the outcome might look the same, but the intent makes all the difference in how the recipient feels.

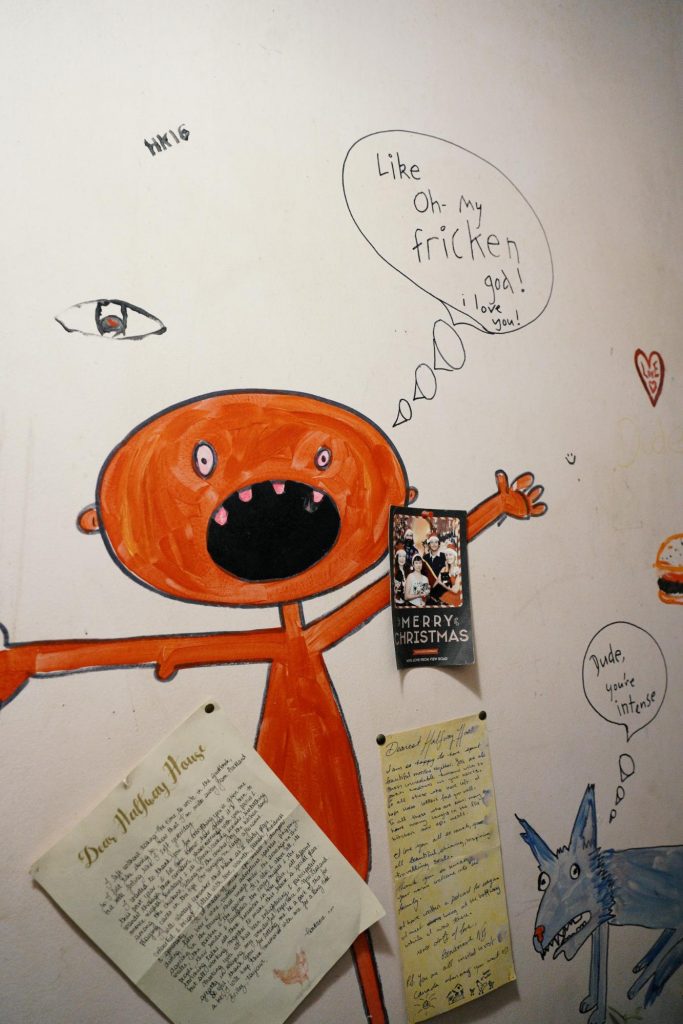

After landing in Auckland, I receive the same friendliness from Sam, the manager of Otautahi Tattoo (featured in the cover image). I might be in New Zealand’s largest city, which anyone might stereotype as cold and clinical, but my conversation with him about the country’s tattoo culture is instantly comfortable that I forget we’ve only just met. For two days, I hang out in his tattoo parlour and watch his customers get inked, most of whom are surprisingly open to letting this random Asian woman look in on a personal moment.

I even convince one student from Sweden, who’s in New Zealand for a personal holiday, to go through with his tattoo. It’s his first ink, so he gets cold feet just before going under the needle.

You’ll be alright, I reassure the dude, as if he’s not about to make a permanent decision based on a total stranger’s advice. The whole process is pretty underwhelming, including the pain.

Call me a believer. Back home, I would probably have kept to myself, and tried to fit in with the average aloof Singaporean. But it hasn’t been 72 hours, and I’ve already demonstrated whānau with someone who’s not even Kiwi himself, as though merely being in this country has made me want to be friendlier and less guarded.

Whānau operates from a rooted sense of trust and faith—the kind that many Singaporeans mistake for gullibility—and stems from believing that it is inherently worthwhile to keep one’s heart open. As someone who’s used to fundamental distrust and cynicism in my countrymen, whānau is refreshing and, like the chilling winds in New Zealand’s summer, its absolute warmth is unexpected.

After five days in Auckland, I head to Rotorua, a smaller city on New Zealand’s North Island that’s famed for its geothermal activity and Māori culture. At its more intimate size, I expect its locals to be more tight-knit, and for whānau to be more apparent.

Even so, it’s nearly impossible to be prepared to feel like family when you are a foreigner.

In another instance, Serene Leong, who heads the sales in Asia for Te Puia, opens up to me about her life story after dinner one night. Having fallen in love with Rotorua on holiday when she was 30, the Kuala Lumpur native never went home. But as we lapse into a mix of Singlish, Mandarin, and Bahasa Melayu, I am home.

A large part of experiencing whānau’s full effect is knowing how to be open to receiving it. After all, far more people know how to give love than to receive it. As far as I know, the key to doing the latter well is wholehearted gratitude.

When I eventually leave Rotorua after being showered with unconditional care and compassion, I am reminded that the absence of a good thing can ironically leave one feeling full.

In my last few days in a country that I’ve grown to love, I usually develop an unbearable urge to be fully present. I become obsessed with savouring and memorising every insignificant detail, from the way the supermarkets are stocked to the specific angle of the bend in the road leading to the beach. I want to take everything with me.

Of course, this is impossible, because in the months after I return to Singapore, I will eventually forget the narrow road I drive to Lake Kaniere, where my colleagues and I play tag with two young boys. I will forget how the kind welcome I receive from the Jamaican owner of Bonz ‘N’ Stonz (a jade-carving store in Hokitika’s city centre) floors me, despite already being familiar with whānau, that I end up spending the entire day in his store. I will forget that I devour piping hot fish and chips at the benches near the entrance to the city centre, as the frigid winds whip through my thin pullover.

In this sense, experiencing whānau makes me believe in kampung spirit again. I can retain the same sense of belonging simply by displaying the exact warmth that I’ve received to the people I meet back home. Whether it’s more consistently checking in with friends, making conversation with a neighbour I see every day, or helping out an industry peer when convention dictates that we should be competitive, whānau is mine to embrace however I wish.

Most importantly, it’s about being more intentional and sincere with my actions. Anyone can open their doors to a stranger, but doing so without expectation for reciprocity is true whānau.

As the Kiwis have shown, paying it forward is the most effective way to receive.

When the pilot welcomes me home, it feels like I’ve never left.

Even though something in me has irrevocably shifted, how much can a person change in 14 days?

As I wait at the baggage carousel, I realise the answer is … a lot. I scroll through my photo album from the trip, and one photo catches my eye. It’s nothing outstanding, just a deep blue lake with an accidental crop of someone’s head in the foreground. But it reminds me of Denise and Howard, an elderly retiree couple I meet on this boat ride to Mokoia Island.

In the brief one-hour journey back to main land, I learn that the island tour is Howard’s Christmas gift to Denise. They’ve come to the island in hopes of spotting a unique bird species. Prior to spending their golden years traipsing the world for birds, the two Kiwis worked at a supermarket, where they fell in love decades ago.

All it takes is one hour, but as Denise and I embrace as we part ways, I damn near choke up. I pass them my number, and ask them to look for me in Singapore if they decide to visit, fully aware that part of the beauty of falling in love with strangers on holiday is knowing you can never see them again.

No hardened and world-weary Singaporean will admit this, but whānau works precisely because it teaches you to stay soft in the face of everything that threatens to get your guard up: betrayal, hurt, and pain. With strangers, it encourages you to approach them with openness, not hostility.

The truth is, though it might feel counterintuitive to many, soft things are harder to break.

And instead of moving mountains

Let the mountains move you

It takes me 14 days to stand corrected: people are mountains. Both are forces of nature, each with the power to destroy, but also the resplendence to inspire. Both are overwhelming and intense; their magnitude often leaves you wanting.

And just like how a sheer glimpse of the mountains can spoil your travel expectations forever, all sorts of people will come into your life. A few will try to change you.

If it’s love, the best thing you can do is to let them.

Visit newzealand.com to act on your wanderlust, and singaporeair.com and airnewzealand.com.sg to book your flights.