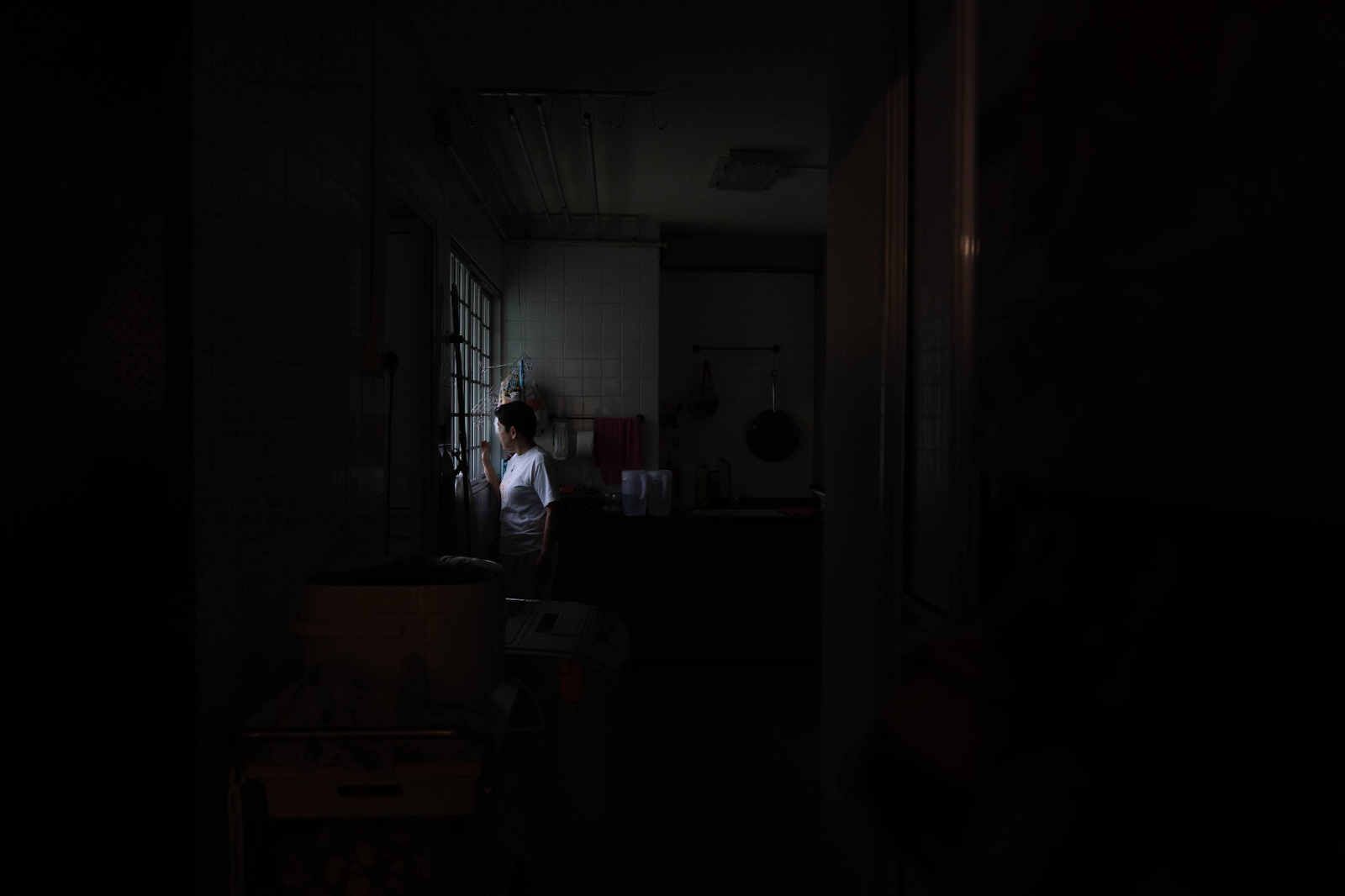

Top image: Nicholas Chang / RICE File Photo

To the families who don’t argue but also don’t really know each other: I see you.

In my case, I don’t know if my siblings are dating anyone. The family hardly eats dinner together. My weekends are a mystery to them, and theirs to me.

But I guess you could say we’re on good terms. Then again, can there really be tension when there’s hardly any conversation?

Going by the statistics, most Singaporean families are resilient and close-knit. And they’re everywhere you look: enjoying picnics in parks, going to the movies together, taking up whole rows on the MRT. Some of my friends speak of “family meetings”, where they update each other on their lives and table discussions on family matters.

The idea that families are warm, happy, and close-knit is entrenched in our society—it’s the default way families should be. Being family-oriented is supposed to be a green flag. In the national narrative of our social compact, families are the first line of support.

But it’s also this expectation of familial closeness that can lead to shame and guilt when people feel distant from their own parents and siblings.

There’s this unspoken fear that something is wrong with them—that they’re some sort of emotionless robot or broken on the inside.

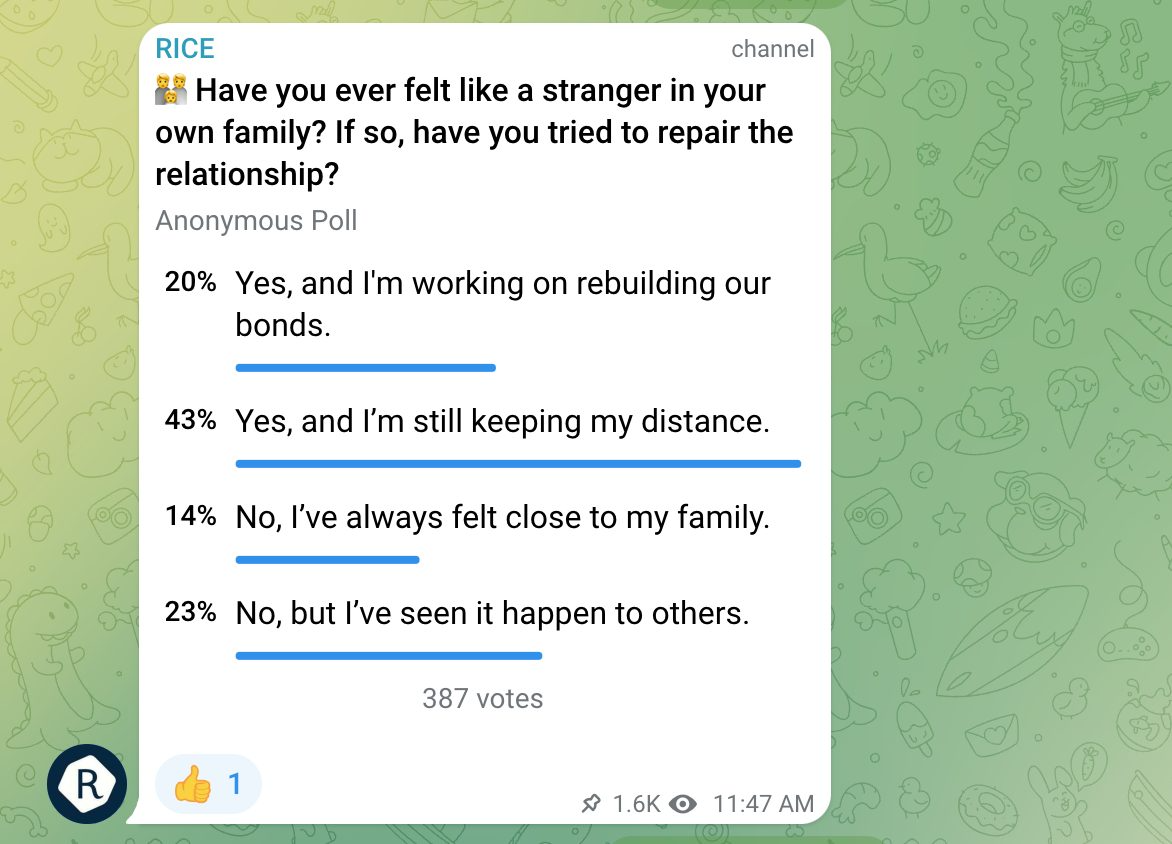

63 percent of 387 respondents in an informal RICE Telegram poll said they do feel estranged from their family. Only 20 percent said they were working on rebuilding their relationship with their family. Others said they would continue keeping their family at arm’s length.

What gives?

This disconnect, particularly prevalent in Singapore, might be attributed to our cultural tendency towards stoicism. As a 2012 Gallup survey suggests, we’re among the least emotionally expressive people globally.

While these surveys that reduce complex emotions to simple data points should typically be taken with a pinch of salt, Gallup’s not far off from reality. For those who value civility over intimacy, a superficial, hi-bye relationship may seem less emotionally taxing than confronting deeper, more vulnerable feelings.

To be clear, we are not talking about families that have drifted apart due to trauma, abuse, or toxicity. Instead, we’re focusing on families whose once-strong bonds have somehow faded over time.

If you, too, feel a strange, unspoken distance in your family and want to bridge it, Anusha Balasingham, a professional counsellor on end-to-end therapy platform Talk Your Heart Out, shares her insights.

Is it normal to just not be close to your family?

Every family’s situation is different. Just because you aren’t close to your family doesn’t mean you’re damaged beyond repair, according to Anusha.

If you are all still talking occasionally, there isn’t much cause for concern, she says. After all, everyone’s busy with their own lives, and we tend to be more connected with friends than family.

But if you’re in a situation where you constantly eat meals alone, go about life alone, and feel that talking to your siblings is weird, then maybe therapy is necessary to help you rebuild your relationship with your family, says Anusha.

When you’re talking it out amongst yourselves, there’s no neutral third-party viewpoint, she explains. Any third party you bring in would most likely be someone in your circle. A neutral third party like a therapist would be able to hear both sides of the story and help you to process the entire situation.

While we typically struggle to pinpoint exactly why we feel emotionally detached from our families, Anusha points out that it can actually be a protective mechanism.

A lot of times, your body knows what it wants.

“So if I feel that, if I talk to my parent, I’m going to be very distressed, then the body will come up with signs like, say, stomach pain,” Anusha explains. “Your body is already telling you that it doesn’t feel comfortable.”

“To answer the question, can it be salvaged? Yes, it can be salvaged. You need to be honest. Having the first conversation is always going to be odd.”

Anusha’s pro tip is to divide and conquer. Instead of meeting as a family, meet each member individually. Tell them what you miss in the relationship and why you want the relationship.

“Use the term ‘I’. Instead of saying, ‘Why did you do this, that’s why I cry’, try saying ‘I felt upset’.”

How can I let go of the expectations I had of my parents when growing up?

We all have expectations for all our relationships, be it friends, family, or our romantic partners.

With parents, we often tend to expect a bit more because they are our main caregivers the moment we’re born.

“And let’s face it, the norm is that the main caregivers, who are the parents, naturally, are supposed to give love and affection to the child,” Anusha adds.

Issues, however, arise when parents do not know what their child’s love language is.

“So we always say, ‘I’m doing this for you. I love you. That’s why I’m scolding you.’ But it may not be the love language for the child to receive it.”

This conjures memories of my parents striking my siblings and me with rattan canes when we misbehaved. When we cried, they’d often say it was for our own good.

Anusha emphasises that you have to acknowledge and validate your feelings. For example, this could mean telling yourself: “I am not feeling the love because this is not my love language.“

Another thing to remember is your parents are human and have their limitations. They are from a generation where talking about love languages and emotions is considered taboo even today. Meanwhile, you’re in a generation where talking about your feelings is considered the norm.

When I think back to the canings I endured as a kid, I still don’t see it as love; using corporal force instead of clarifying our mistakes to us was the easy way out. But did our parents’ generation really have the emotional tools to gently parent us? Probably not.

The third thing to remember is to separate your identity from your family’s actions. Know that what your parents might have done to you has nothing to do with you as a person. Just because they’re angry does not mean they don’t love you. Nor does it mean that you aren’t worthy of love.

The fourth point: grieve.

“We don’t actually give ourselves time to grieve that this is not the relationship we expected to have with my parents. It’s okay to feel sad and to accept it,” Anusha assures.

The next step is to forgive them for your own peace. It’s not about excusing their actions. Rather it’s more about allowing yourself to release all that anger and resentment you have in you.

And, unsurprisingly, Anusha’s last tip is to seek therapy so you don’t inadvertently let your trauma affect your other relationships.

“A lot of us in Singapore are not compassionate for ourselves. There’s a lot of self-blame. Sometimes, we pass it on to our children without realising it, so it becomes an intergenerational trauma.”

I feel that I am carrying out my responsibilities as a child because of obligation and not out of familial love.

Besides laws that compel us to support our parents, there are other unspoken rules of filial piety. We might find ourselves going through the motions, for example, visiting our parents just to “show face”.

In Singapore, we do many things out of obligation rather than love. Some people even stay in marriages out of obligation, says Anusha.

But you need to accept that sometimes, there’s nothing you can do to change your family dynamics. You can still do your part if you feel obliged to but do be cognisant of boundaries.

“A lot of people think, ‘If I step aside, if I set the boundary, that means my parents are going to think I’m a bad child’. No. Actually, it helps both of you. Setting healthy boundaries is very, very important.”

As much as they are your parents, if they’re still hurting you, there’s no point allowing yourself to get hurt. Boundaries could look like limiting the amount of information you share with them, or even limiting contact, Anusha advises.

We’re sometimes too focused on what society is going to say. But we need to understand it’s okay to be detached. It’s a form of self-protection, and that’s fine.

Is it wrong to be completely okay that I will always feel detached from my family?

Distance doesn’t just happen. It likely has always been there, but you may not have realised it.

There’s a reason it happens, according to Anusha. When we’re growing up, our pre-frontal cortex—the thinking portion of our brains—isn’t fully developed yet. We tend to create narratives based on our parents’ actions, with the emotional part of our brains.

The narratives we latch on to can stem from innocuous things.

“The mum or dad could be joking, ‘This just looks so tight on you.’ But the narrative the child may create is that they’re fat. That seed is enough for distance to grow.”

You may not realise it, because there are a lot of positive experiences as well. But that one negative thought might be so strong that you don’t feel a connection with your parents.

Again, Anusha prescribes therapy if you want to untangle that knot and find the root cause.

How should kids navigate emotional immaturity in their parents?

There are two likely scenarios. The first is one where the parents have been emotionally immature and they don’t realise it. If they are the kind of people who are willing to recognise it and change themselves, then by all means, go and tell them off, Anusha says, half-joking.

The second scenario is where parents manipulate. They’ll tell their kids things like “It’s because of you that I am behaving like that.”

“Don’t even try to tell them off because a manipulator will find ways to continue manipulating,” Anusha affirms.

It can be tempting to compartmentalise your emotions, but that’s unhealthy. Talking to someone about it can actually help to regulate the emotions you’re feeling. A therapist can help you figure out the next steps, as well as short-term and long-term goals.

It’s also always good to write down what you are feeling or what happened. You could keep a diary, draw it out, or even write a poem. This helps you process what happened.

Why does it feel so hard to open up to my parents about my life? It’s so much easier to open up to friends.

This is perfectly normal, Anusha assures. One of the major root causes is the different perspectives and belief systems of different generations. You might find it much easier to relate to your friends.

Broaching sensitive topics with parents can also come with a fear of judgment or disapproval. You might think: “If I tell them I’m struggling with this, what are they going to say? Are they going to accept me?”

In a nutshell, you don’t feel safe in your relationship with your parents. Like feelings of detachment, this, too can stem from small instances.

Say if a child fails an exam, the first question a parent might ask is, “Why did you fail?” They don’t explore what made the child fail. This is enough for children to build their own narrative that they can’t talk to their parents.

The parent has to be the one to make the first step because the child has already concluded they don’t feel safe.

For parents who want to create a safe space for their kids to open up, Anusha suggests winding down together in the evening. Finish all the schoolwork before dinner. After dinner, have your family time where you can sit down and talk to your child.

As a parent, always start by talking about small, minor details and sharing about your day. You can talk about how you feel at work. Find something that interests the child like, say, maybe some movies or music.

You should also set boundaries. Allow your children to call you out if they find that you might be overstepping. For example, they can say, “Hey, Mum, you shouldn’t say that!”

If you are an adult who is taking the initiative to try to connect more with your parents, the approach is similar. But you have to be aware of whether you’re approaching your parents as a fellow adult or if it’s your inner child.

“There’s an inner child in all of us. Every time I see my parents, even though I’m an adult, I’m seeing my parents as if I’m a little girl. My expectation is I want my parents to sayang me,” Anusha remarks candidly.

This is where working on yourself comes into play. If you can relate to them adult-to-adult, then you can have a constructive conversation.

But if you’re approaching things child-to-adult, your emotions may come out. You may get angry, and you’re going to start raising voices, saying things like, “Why didn’t you do this? This happened because of you.”

Trying to speak to family after a long while can feel immensely awkward. That’s completely okay.

When you’re trying to speak more with your parents, just go out with them. Ask them how their life is going. What was their life like? Everyone has a past, and every past contains a lot of baggage. Their generation chooses not to talk about it. The current generation does.

How can people improve their relationship with their families if family counselling isn’t an option?

If everyone who needed therapy went for it, the world would probably be a better place. Alas.

“We do have clients whose parents are not willing to come, so we can’t force them. Sometimes, it does help if they see the difference therapy makes,” Anusha concedes.

If you can’t get through to your parents, go to therapy as an individual first. Get yourself the tools you need to work on your emotions, and who knows, there could be a domino effect.

What Makes a Family

There’s this incredibly cheesy saying among primary school kids: Family stands for ‘father and mother I love you’.

These days, though, the changing ideas of what ‘family’ is have made it less taboo to cut off toxic relatives. Simply sharing genetic material with someone else doesn’t mean you’re automatically bound together for life.

There’s also more acceptance of non-traditional family structures. A single couple with a dog can be family. A commune of friends renting a home together can be a family. Platonic life partners can be a family.

You don’t need to have a traditional family if you don’t want to. And you should never feel compelled to stay in contact or rebuild connections with toxic family members.

For the people who do want to bridge the unspoken gap with their family but feel terribly awkward about making the first move, I get it. It can be tempting to let your familial relationship dry up if there are other more rewarding, uncomplicated relationships in your life like, say, your friendships.

But Anusha’s explanation left me with a realisation: it’s the things left unspoken that fester and drive people apart. Glossing over messy emotions is quintessential Asian and Singaporean culture.

We often think of keeping quiet about things as keeping the peace. But why should we let the temporary discomfort of a candid conversation rob us of what could be a rewarding relationship?

And if that conversation goes south, then well, can you really say you’re worse off?

Editor’s note: Article has been updated for further clarification.