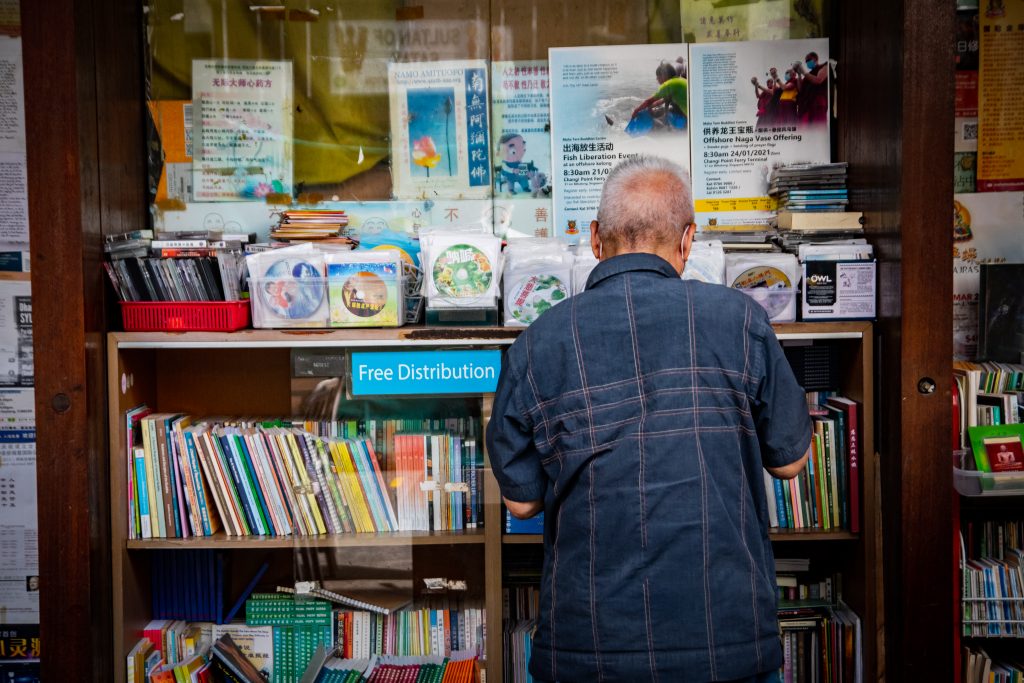

All photography by Liang Jin Tey.

“I don’t mind giving my parents an allowance,” said one RICE producer. “What I dislike is the expectation that I must give them an allowance in order to be considered a good daughter.”

“I wouldn’t want my future children to deal with the same pressure.”

“For me, it’s very simple lah,” said another RICE colleague. “The parental allowance isn’t just an expectation, but a duty. Honouring our filial duties towards parents is the only thing separating humans from beasts.”

This was followed by an awkward silence as they glared at each other from across the conference table. Then, in unison, they turned and looked at me.

“So obviously, Singaporeans feel very strongly about this issue,” I offered.

What else could I say? It was none of my business.

In Taiwan, the parental obligation is quite straightforward. If you live at home, you’re supposed to give your parents a monthly allowance to help cover expenses—whether they need the money or not. If you rent or live abroad (like me), it’s standard to overcompensate with a fat ang bao on CNY. For most 9-to-5 workers, this is roughly one month’s salary, or the bulk of their year-end bonuses.

Sure, we all grumble about it. But the whole ‘old people are too entitled’ argument has never made its way into mainstream discourse.

In fact, I can’t recall ever coming across this argument … until I moved to Singapore.

Have Chinese Family Relationships Become Too Transactional?

Like clockwork, the issue of parental allowance and filial piety once again made recent headlines. Some young Singaporeans argue that norms are changing, and that future parents shouldn’t rely on their children for their own retirement needs. Others, like Bertha Henson, believe that the parental allowance should be further ‘ingrained and hardened’, as it is an ‘emotional tie’ between the parent and child.

The State seems to agree with this traditional viewpoint. In Singapore, providing financial support for parents isn’t just a cultural expectation, but the law. The Maintenance of Parents Act enables parents who cannot sustain themselves to take their children to court to demand a monthly allowance if it’s not done willingly.

But for many of the young Singaporeans that RICE interviewed for its recent video on filial piety, this combination of emotional and legal blackmail are the last straws in a long list of pressures that have been heaped on the young — in an economy where they can barely keep their own heads above water.

These rules are also too restrictive. What’s a child’s ‘filial duty’ in an abusive or toxic relationship? How should we handle the issues of care-taking and long-term illness in a rapidly ageing society? What about mental health and dementia?

Finally, is it healthy for the parental allowance to become a shorthand for a child’s love? What impact will this have on family relationships?

To make sense of this debate, maybe we first need to unpack how filial piety has traditionally been understood (or misunderstood) by the average Singaporean.

Let’s Ask Uncle Confucius

There’s a certain demographic of Chinese-Singaporean Boomer who have become self-anointed defenders of ‘conservative Asian values’, taking it upon themselves to protect Singapore from the threat of ‘Western liberal ideologies’ that would ‘never work in Singapore.’

Except in every case where it has.

To this end, Confucius is often invoked as the vanguard to this ‘culture war’ for Singapore’s soul. Confucian concepts like filial piety, devotion, and respect for authority have long been used to justify the status quo, dating back to the early imperial dynasties of China.

But I’ve actually read Confucius. Who knew that my lost childhood spent tearfully copying the Analects by hand could one day be harvested for Singaporean content?

One of the biggest misconceptions is that Confucianism somehow encourages a blind obedience to authority. While there’s definitely an element of hierarchy involved, this is arguably a moral hierarchy rather than a suggested org chart. More importantly, this hierarchy confers responsibilities on all parties, from parent to child, ruler to ruled. It is very much a two-way street—something that Chinese Emperors in each successive dynasty conveniently ‘forgot.’

I want to highlight three relevant sections from the Confucian Analects (論語) on filial piety and explain what it means in the Singaporean context.

All translations are mine:

1. On Dogs and Horses:

Original Text: 子游問孝。子曰:「今之孝者,是謂能養。至於犬馬,皆能有養;不敬,何以別乎?」

Translation: “What is filial piety?” asked a disciple.

“These days, filial piety means to be well provided for,’ said Confucius. “But one can also provide for dogs and horses. Without respect, what’s the difference?”

Commentary: According to Confucius, money should not serve as the basis for any parent-child relationship. Providing for our parents’ material comforts may give off the illusion of filial piety, but it can’t replace the core values of respect and gratitude.

To think otherwise would be to suggest that richer families in Singapore have more love to give. When in fact, there are other ways of showing love besides money, like taking your parents to the doctor, exercising together, cooking for them, or calling to check in on them every couple of days.

Parents must also ask themselves: do I actually need an allowance, or is it simply a ‘face’ thing so that I can brag to my relatives and friends? When I complain about how little my child gives, do I prefer the ‘show’ of filial piety over the substance?

2. On a Child’s Duty

Original Text: 孟武伯問孝。子曰:「父母唯其疾之憂。」

Translation: “What is filial piety?” asked a disciple.

“Conduct yourself in such a way that your parents only need to worry about your health,” said Confucius.

Commentary: This is where the two-way street comes in. The lesson here is that COMMUNICATION with our parents and family is critical in any working relationship—to the point where your health becomes their only concern. This means patiently explaining your thought process and life choices to them—and not immediately getting defensive and closing yourself off. It may be unpleasant or fall on deaf’s ears, but nevertheless, this is a child’s duty.

There may be things our parents’ generation may never completely accept or understand, but they need to trust that you’re working towards something. That you have a plan, and are accountable for your own life and livelihood.

3. On Effective Governance

Original Text: 子曰:「道之以政,齊之以刑,民免而無恥;道之以德,齊之以禮,有恥且格。」

Translation: “If you rule your people with politics and check them with punishment, then they will naturally become unruly. If you rule them with virtue (de) and check them with propriety (li), then your people will learn to self-regulate.”

Commentary: I’ve been thinking about this passage a lot ever since moving to Singapore. Why are Singaporeans so kiasu? Why do sinkies pwn sinkies? Why is it that despite the abundance of fines and regulations, this hasn’t stopped the average Singaporean from finding creative ways to skirt these restrictions?

Compare this to a society like Japan, where despite having few explicit rules governing daily behaviour, the Japanese abide by unspoken rules and etiquette, driven mainly by peer and social pressures.

While there are certainly pros and cons to each approach, I can’t help but notice the diminishing returns of Singapore’s top-down model. This is why I’m against the Maintenance of Parents Act, not because I disagree with the sentiment of wanting to take care of our elderly, but because it sets a litigious climate that pits siblings against each other, and parents against their own children.

A parent may win the judgement, but they will have lost the relationship.

So What?

At the risk of playing the politician, I can see both sides of Singapore’s filial piety debate.

Family dynamics are such a complicated and emotionally fraught subject that it’s almost impossible to prescribe a one-size-fits-all solution. This is further complicated by increased cost of living, a pandemic-driven recession, and demographic realities like an ageing population, as well as fewer children to shoulder the load of care-giving and medical expenses.

The pressures that young Singaporeans face are real. They’ve already experienced two Great Recessions, while digital disruption has upended traditional career paths and notions of financial stability.

Yet, if young people were being truthful, we also have not shown our parents as much time, love and attention as they perhaps deserve. Even as we assert that “money isn’t everything.”

So to take a page from Uncle Confucius, here are a few pieces of advice that generally apply:

Dear Parents, to expect a monetary return for selfless acts of love is neither selfless nor love. And if you treat your children like a retirement plan, they will treat you like a financial burden.

Dear Kids, you’ve only got one set of parents. They are imperfect. Just like you and me. We are also entering the last 10% of our days with them. And insofar as time and money can express our priorities, invest those resources accordingly.

Don’t come to regret it when it’s too late.

Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.