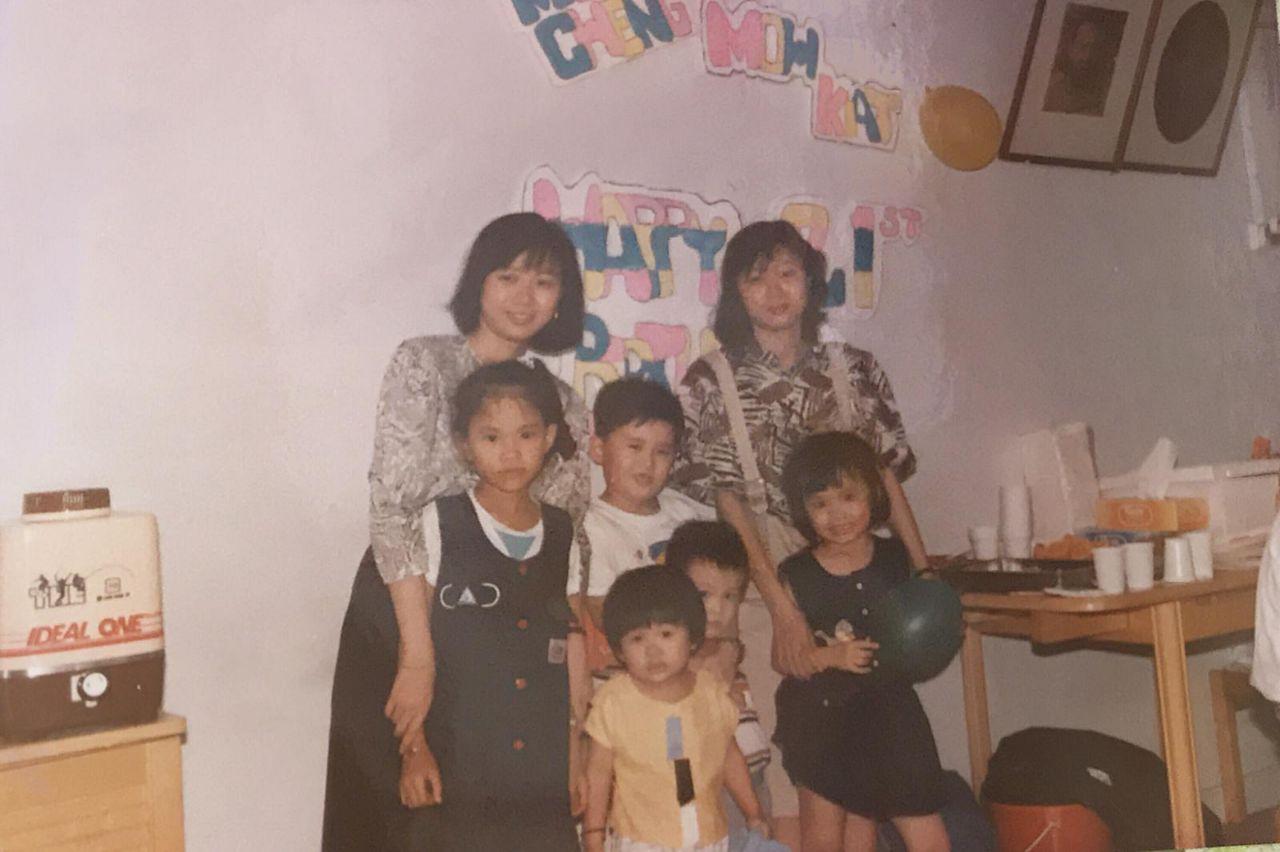

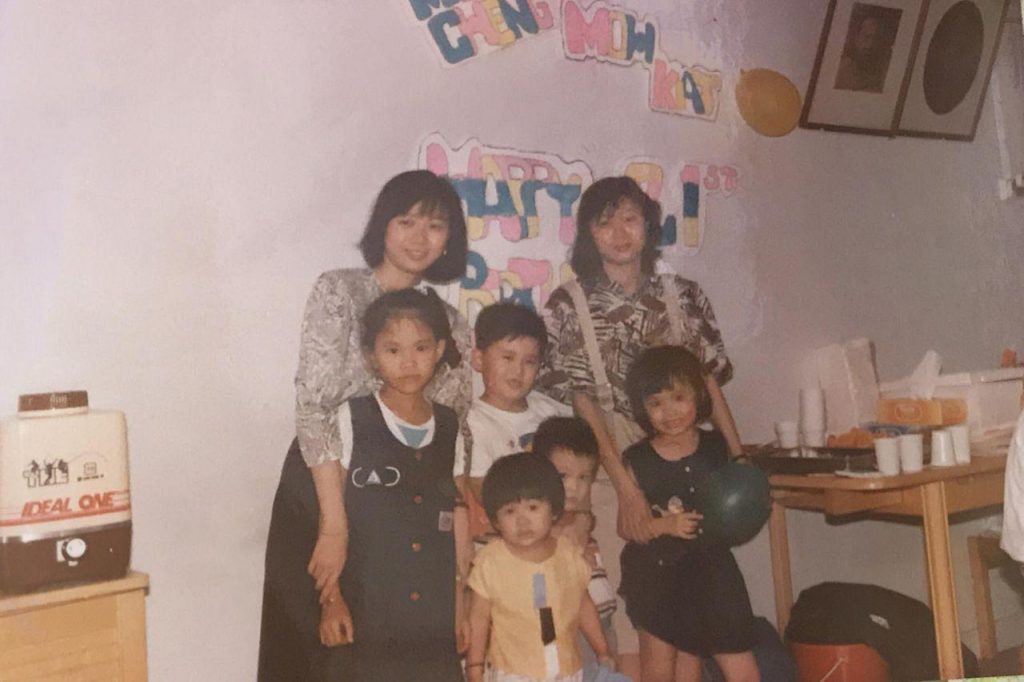

For as long as I can remember, my mother has been dyeing her hair once or twice a month. It has gone through phases: dark brown, brown, reddish-brown, all kinds of brown. She always kept her hair short; a thin, layered bob with white roots fading into box dye-brown. That her greying hair was kept out of sight meant that the idea of her actually growing older was, for the most part, out of mind.

The first time I fully understood the fact that my mother was ageing was when my aunt’s arthritis started to worsen. And, since they were twins with the same illness, my mother’s condition soon followed.

This year, there are no celebratory dinners at Lei Garden, only listicles of bakeries that will deliver Mother’s Day cakes to your doorstep.

The pain was something she mostly mentioned offhand. We never saw her cringing because her joints were swelling up or complaining about how she could barely move her fingers. And so it was something I often dismissed. We never spoke much to begin with, and we weren’t about to start with the topic of a chronic autoimmune disorder that might leave her bedridden a couple of decades down the road.

Her health did not deteriorate drastically. In fact, she’s still moving about, going to work, doing the usual stuff. But, over the years, each time I saw her on the weekend back from campus, the wrinkles on her face seemed to deepen and the air around her carried a little more weight. These realisations left me with a vague sense of confusion. How was I, an emotionally distant daughter to an emotionally distant mother, supposed to feel about the very real fact that my mother was getting older?

For those whose parents are older, in their 70s or 80s, the idea of mortality might seem that much more real. In 1981, social worker Dorothy Miller described the “sandwich” generation as those who had to simultaneously take care of both their children and elderly parents. Stress then comes from multiple places: anxiety about ageing, avoidance as a coping mechanism, worries about whether your mother has decent health insurance, what if they need to move to a nursing home, and so on.

In Singapore, where the median age of mothers giving birth for the first time is relatively high—30.3-years-old, compared to 26.3-years-old in the United States—the reality of that our parents are ageing will hit us much earlier in life.

For some people, it might come in the form of a sudden incident like a hospitalisation. For others, it might be more gradual. You watch your elderly parents slow down both physically and mentally, and the steady way in which this happens is almost cruel in how it forces you to accept mortality—both your parents’ and your own—and anticipate loss.

It is a bit too early for me, I think, but I am anticipating this loss. Each time my mother goes on a juice diet to relieve the pain in her fingers, elbows, and knees—the only time I ever see her slice fruit is when she chops up two whole bags of celery to jam down the Hurom—I am reminded of the fact that her body is not what it used to be. Each time she speaks with my grandmother, who has grown quieter as she has grown older, I ready myself for the day that I have to start thinking about health insurance and life insurance and wills, as morbid and overwhelming as these thoughts might be.

I count myself lucky. I acknowledged very early on that this loss will happen eventually; hopefully, it will come many, many years down the road. This means that I have that much more time to understand what exactly my relationship with my mother is.

Stereotypical unaffectionate Asian parent-child connection? Check. Pressure to do well academically throughout my formal education? Check.

But, in motherhood and daughterhood, there must be more than just a series of distant, transactional interactions. The knowledge that, someday, she might be too bedridden or senile to articulate to me who she really was, what her life was like, or what shaped her as a person, ignites in me an urgency to figure these things out as soon as possible. Juliet Nicolson wrote of tracing her maternal family history, but only after her mother passed away: “Daughterhood is the one state that every woman on the planet has in common.”

And I agree. I want to know who my mother is. Maybe, if I can grasp that, I can understand who I, a daughter, am supposed to be.

Four years on, I have grown older too. Perhaps when I head home, her hair will be streaked with white again. Maybe her pain is finally subsiding because it’s been a month since the juice cleanse. These few weeks of the circuit breaker have granted me more time to navigate my daughterhood, so that I can celebrate her motherhood. We will have meals at the dining table, go on morning walks at the nature reserve, and try in vain to clean the juicer. I will make sure of that. No matter what happens, I am certain that I will be reminded of the very real fact that as she is growing older, and so am I.