“All the reliable sources you can lay your hands on are here. Name them.”

Cheong had been chief editor for nineteen years, but instead of going gently into that good night, he penned a book. In it, Cheong spilled the beans on the rumoured threats, dreaded intimidations, and softer touches employed by founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to ‘handle’ the press during his reign. Why?

“…[Cheong] did not want to leave behind the legacy of being a government lacky,” speculates PN Balji, six years later, in his own book on Singapore’s early media history, titled Reluctant Editor.

In fact, it was Cheong’s memoir that inspired Balji to write Reluctant Editor, which he insists is ‘not a memoir’.

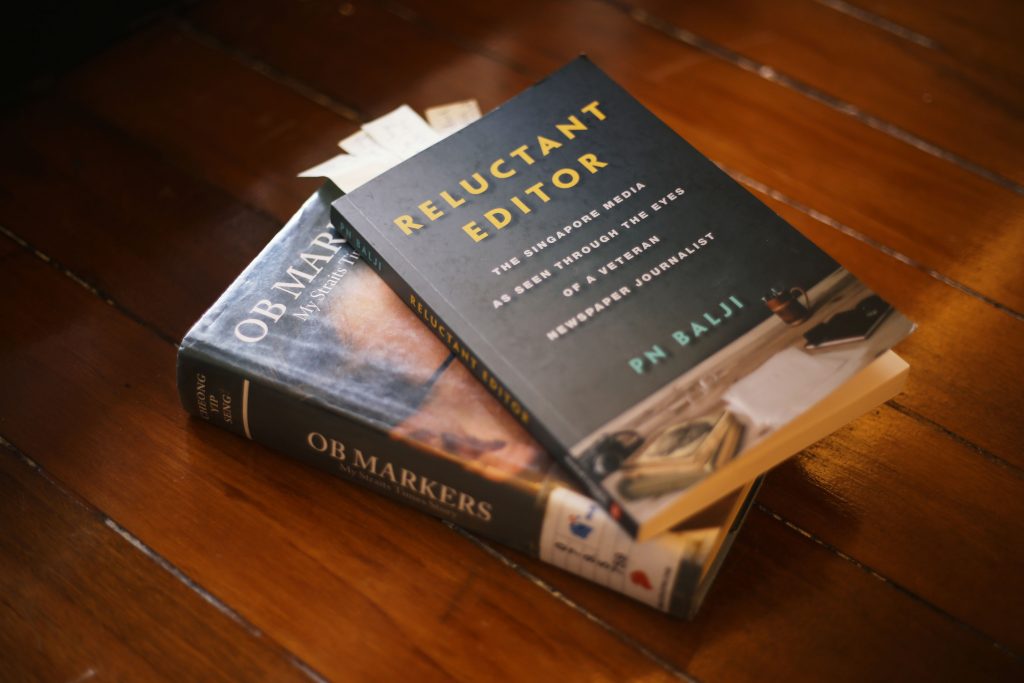

The two tell similar stories: of plucky journalists and stressed editors, fierce competition and government pressure, early warnings and last-minute ‘stop-the-presses’. But that’s where the resemblance ends.

Cheong’s memoirs are long, laborious, and rich with detail. Sometimes, they’re a little too rich. OB Markers had two purposes: to educate the public on LKY’s legacy of media controls, and to provide a resource for future historians. That’s all well and good, but it renders OB Markers somewhat inaccessible to the everyman.

The answer? Reluctant Editor.

While OB Markers is the story of a career groomed wholly within the establishment, Balji’s career is strikingly different though no less impressive.

From the get-go, Balji describes his early years as a journalist at Malay Mail and New Nation, followed by editorial and management positions at The New Paper and TODAY. Besides a brief stint at ST, Balji’s story is practically the inverse of Cheong’s.

In later chapters, Balji leads us through the twists and turns of brand-new media endeavours, from the launch of The New Paper in 1988 to the release of TODAY in 2000.

Some stories, like business meetings with advertisers and printers, are a yawn. Others, like retellings of ST’s devious tactics to undermine their competition, and descriptions of its fearful newsroom culture, offer pointed criticism of the corporate and government-minded monopoly that used to exist in Singapore media.

But we’re not here for the particulars of newspaper formatting and media business deals. To the seasoned media hawk, these chapters provide some added garnish—but most readers are, quite understandably, reading for the meat, or as Balji puts it, ‘Living Dangerously’.

Back in the Wild West days of the ‘60s, crime reporters mounted all kinds of (thoroughly illegal) hijinks to pull their stories. In one instance, Balji recalls how a group of reporters, including himself, ‘rewarded’ 999 telephone operators for tip-offs on crime stories.

It didn’t last very long.

Balji and his colleagues pleaded guilty and were fined $1,000 for corruption. The telephone operators were all fired.

“We were packed off to the CPIB office in Stamford Road, isolated in separate cold rooms and interrogated for nearly 20 hours.”

Inevitably, Reluctant Editor will be measured opposite its predecessor, OB Markers.

While the latter is something of a history book, Reluctant Editor is far more readable. The language employed is clear, concise, and simple to a fault. On several occasions, I found myself wishing Balji had injected some spicy drama into his prose, purely for my reading pleasure. Without it, the text is sometimes bland. Then again, perhaps that’s the point.

My major gripe with Reluctant Editor is how Balji chose to structure his story. The book is composed of ten chapters, but rather than being organised chronologically, the content is grouped thematically within a loose timeline.

As a result, the book may bewilder some readers, depending on their tolerance for alternative narratives. Some events surface repeatedly in different forms across different chapters, leading to not a little confusion. While I appreciate Balji’s efforts to foreground its themes, I wonder if this stab at ‘simplifying’ the book instead made things a tad more complicated.

Despite this, for the many casual readers who baulked at the prospect of perusing OB Marker’s 400 pages, Reluctant Editor is an absolute must-read.

For forty years, Singapore’s media appeared to be a tightly-managed organisation, in lockstep with the ruling party. With books like these, an alternative tale is coming to light: how some journalists, editors, and media-persons ‘walked the tightrope’ over the Powers That Be in the service of better papers and a better country.

In today’s media landscape, with deliberate falsehoods running wild, social media wrecking the game, and government controls back in the spotlight, we must look to the past to inform our present. Reluctant Editor is a story that must be told—and a story that must be read.