Rice is the official media partner of Singapore International Film Festival 2019.

From time to time, I return to this particular quote by local playwright Alfian Sa’at: “If you care too much about Singapore, first it breaks your spirit, then it breaks your heart”.

From Singapore’s steadfast refusal to demolish the colonial statute of 377A and the continued discrimination of LGBTQ+ members, to the tacit acceptance of casual racism with the brownface saga amongst many more incidents—it can be incredibly disillusioning to be a part of Singapore. In a country that constantly emphasises its economic vulnerability during national day rallies and parliamentary sittings, Singapore’s urban landscape and its people are constantly subjected to the rhetoric of upgrading, change and improvement. Notions of cosmopolitanism, inclusivity and belonging are pegged to specific caveats and inhibitions, where equitable treatment is anything but the truth.

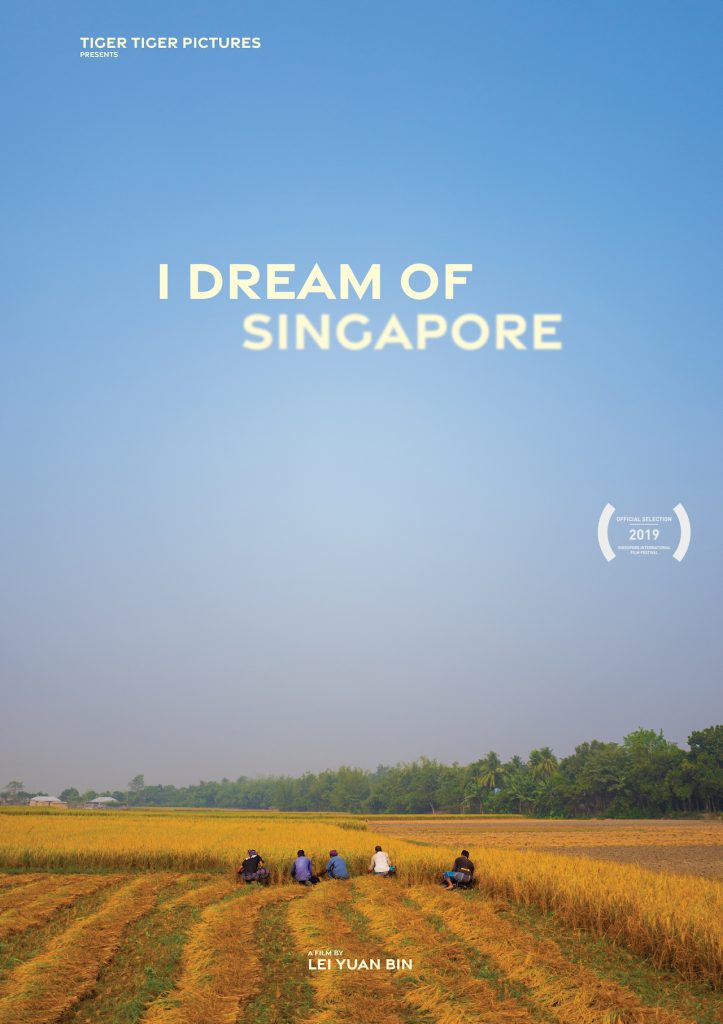

The stories of two such marginalised groups, migrant workers and Normal (Technical) students, are highlighted in Lei Yuan Bin’s I Dream of Singapore, and Yong Shu Ling’s and Lisa Teh’s Unteachable in the SGIFF Singapore Panorama Programme.

A migrant worker leaps over the green fence by the side of the road, only to immediately face the brunt of another security personnel shouting directly in his face. Cornered by another security personnel, the same worker is shoved back into the sidewalk carelessly, as if he weren’t a decent human-being like themselves. Overlooked and othered, migrant workers are only valued for their ability to take up “undesirable jobs” that Singaporeans are unwilling to partake in at low (and unfair) wages, dispensing their hard labour to build landmarks on extreme ends of the spectrum: dispensable and easily demolished, as well as the next jewels of Singapore.

At the same time, Feroz has a 15 cm wound on his belly, a souvenir from his day job at the construction site. Denied “proper medical treatment” by his employer, the country Singaporeans proudly call home is built on the back-breaking labour and efforts of Feroz and many others. Yet, they are still treated with a lack of human-rights and derision—not even deserving of proper food necessary to nourish their labouring bodies. Recently, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted how the Changi Jewel epitomized “dream[ing] boldly” for Singapore, being a symbol of bold dreams. But these very dreams of a nation are supported by the individual dreams of migrant workers to attain a better future for themselves and their families back home.

During an internal meeting within the department of mathematics, the head of department states how the prospect of sacrificing “family time” to put in the extra effort to help out these Normal technical students is simply “not worth it”, thurs preferring traditional teaching methods. Embedded within such a statement is an almost quantitative application of a cost-benefit analysis, with the students being deemed as dispensable units as opposed to actual living beings with futures ahead of them. There also seems to be a thinly veiled insinuation that the children of these teachers are perhaps more important, warranting greater attention as opposed to their own students.

Shuqun secondary school subscribes to different mantras: from “Touching Hearts, Inspiring Learning” to “Dare to Soar to Greater Heights” and “An inviting school that brings out the Best in everyone” that are splayed across the school building. Yet, perhaps such mantras are less aspirational than perfunctory and performative in masking over the realities within the physical school compound.

At the same time, whilst schools seem reluctant to help out students in need, messages of high achievement are still continuously drilled into the students’ heads as they are constantly pressured to achieve good grades. Prior to the end-of-year mathematics examination, a teacher proclaims to the class “I expect nothing less than a distinction from everyone”. Another exchange, rather amusing, goes along the lines of:

Teacher: “You will do well right?”

Student: “No.”

Teacher: “Well, you’ll try your best right?”

Student: “Yes.”

The main character, Damian, expresses his earnest desire to be a chef. An understanding of surds and indices will not teach him to master cooking a bowl of say, prawn noodles. And yet, he valiantly struggles to grasp these mathematical concepts of basic algebra.

These fixations, however, gloss over the humanness of these individuals. Both films delineate the day to day lives of their subjects outside of their associated traditional spaces (work and school) all over Singapore. In Unteachable, Damian celebrates his birthday with his family by barbecuing at the BBQ pit, growing excited as he is gifted a bicycle as a birthday present. Jamie and Tenisha, two of Damian’s classmates, express a desire to become singers, with Tenisha exclaiming that “music is [her] everything”

Meanwhile in Lei’s film, migrant workers are seen visiting and taking photos of the Gardens by the Bay and Marina Bay Sands, two landmarks built on their very backs for everyone (i.e local Singaporeans and tourists) but themselves. In the Dayspace of Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), a non-profit organisation pushing for improved conditions for low-income workers, a small group of migrant workers have their eyes fixated on an LCD TV, watching the FIFA World Cup together.

In a secondary school, a migrant worker delivers a talk to a class of Singaporean students. Holding a Bachelor of Arts from the Bangladesh National University, he is also a poet back home. And yet migrant workers are subject to an odd flattening of identities as he is asked—“You are migrant worker right … How come migrant workers can write poetry?”—as if migrant workers can only be one or the other. Singapore can only see migrant workers for the cheap labour they provide, forgetting how these are human beings with families back home and identities outside of work.

In a country that chooses to celebrate past figures that had literally stolen and pillaged our lands for self-gain and opts to marginalise and push down on members of our community that very much made what Singapore is today, Singapore is a country full of contradictions. And whilst active steps have indeed been taken to deal with such issues, such as the introduction of the weekly rest day for migrant workers and the phasing out of streaming by 2024, more has to be done by the state. Greater structural change and the shifting of mindsets has to occur, where migrant workers are not thought of as bodies to extract labour power from and that academic results are not seen as the metric to gauging achievement.

If we truly believe that art can be used to incite social change, perhaps SGIFF’s 30th anniversary can be twofold in both commemorating the occasion and taking active steps to push for systemic change in the issues surfaced. We, as audience members, also share a larger collective responsibility in doing more. For as we are watching these films in the cinema, outside the screen, there are migrant workers and Singaporean students who are experiencing these lived realities at the very same moment.

All Rice readers enjoy S$2 off the opening film and S$1 off all other titles with the promo code SGIFFxRICE.

Update: The SGIFF screening for ‘I Dream of Singapore’ has sold out, but there will be a special charity screening in aid of TWC2. More information can be found here.