Save for my neighbour’s pesky Pomeranian that has yapped at me every day that I’ve stepped out of my house for the last decade, my neighbours and I aren’t well-acquainted.

On regular days, we don’t exchange pleasantries nor ask how each other is doing, even though we share the same lift. We merely smile at each other in the few seconds it takes for us to get from the fourth storey to the ground floor, satisfied with existing on the periphery of each other’s lives.

I certainly couldn’t find them online if my life depended on it, because, well, I don’t really know their names, okay???

Apparently, however, this non-relationship with my neighbours seems to be the norm. In 2014, the Straits Times reported that there were few displays of trust among HDB residents. Three years later, another poll said Singaporeans preferred privacy to mingling with neighbours. Then, earlier this year, the Singapore Kindness Movement asked if Singaporeans were too “scared” to befriend our neighbours.

Obviously then, I was taken aback to discover that some people actually want to talk to their neighbours, but only on social media. Even then, it’s contained to hyperlocal Facebook groups about their own BTO block.

Earlier this year, a friend (let’s call her X) moved into her BTO flat and became the ‘victim’ of a neighbourly dispute. X’s neighbours were unhappy that she and her husband had left the corridor dusty from their renovation works. This ‘complaint’ was ‘lodged’ on their BTO’s Facebook group, where she was a member, with the goal of shaming X and her husband.

Over the next few weeks, she was met with stony silence when these neighbours took the same lift as her, reinforcing the pointlessness of their BTO’s Facebook group—the singular thing I took away from that anecdote.

Essentially, the BTO Facebook group seemed to be a bizarre concept that represents an entirely novel aspect of the lives of newly-wed Singaporean millennial couples.

However, the purpose of the BTO Facebook group leaves me wondering whether, perhaps, one loses one’s mind after getting married. Surely the groups exist for a good reason, but that reason remains beyond my human comprehension.

Firstly, its very concept goes against the reality of Singaporeans preferring our privacy and choosing to treat our neighbours with stoicism as per reports. As a self-confessed anti-social Singaporean who falls among this demographic of similarly unfriendly citizens, I just want to be able to zone out and live in my own head when I’m walking around in my estate. I’d rather not run into any neighbours if I had a choice.

Unfortunately, consenting to this degree of privacy intrusion and having practically zero separation between one’s personal sharing online and who one is in real life is something I will never understand.

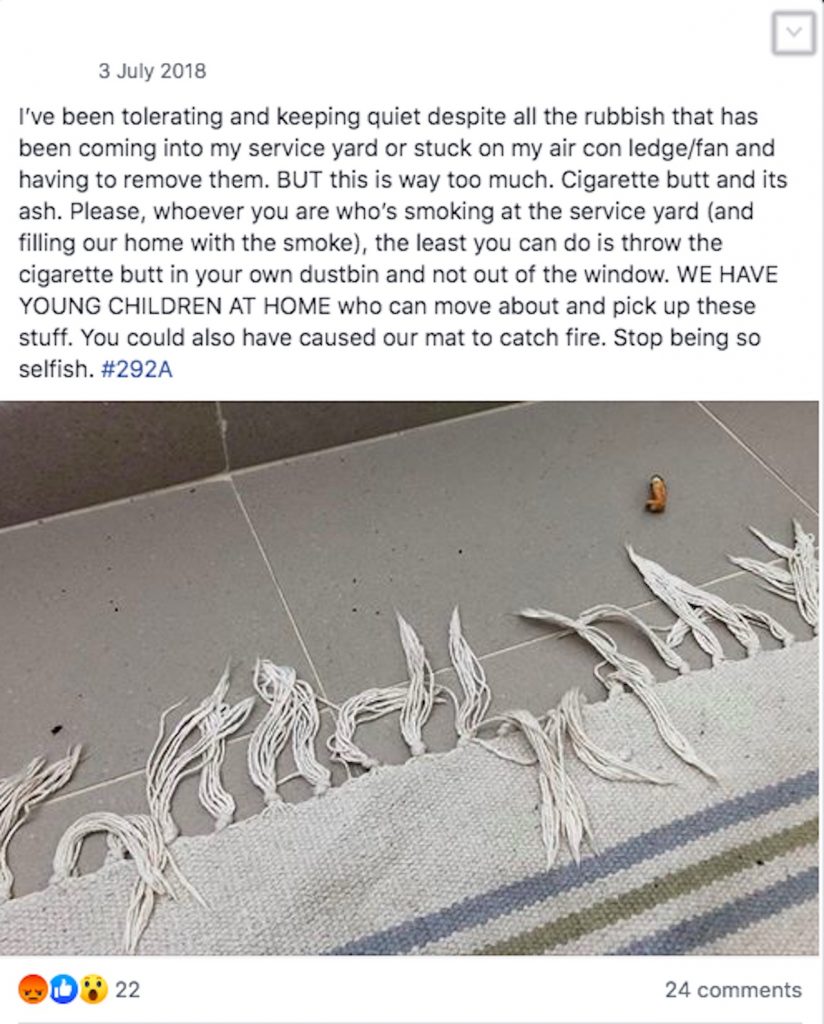

Second, the BTO Facebook group appears like a thinly-veiled attempt to establish some sort of social hierarchy. As my friend X’s story has shown, it can quickly get political simply because human relationships are involved, even if the group might not have begun as such.

In the long run, these petty politics foster resentment and contempt for neighbours—the direct opposite of what was presumably the objective of the Facebook group in the first place.

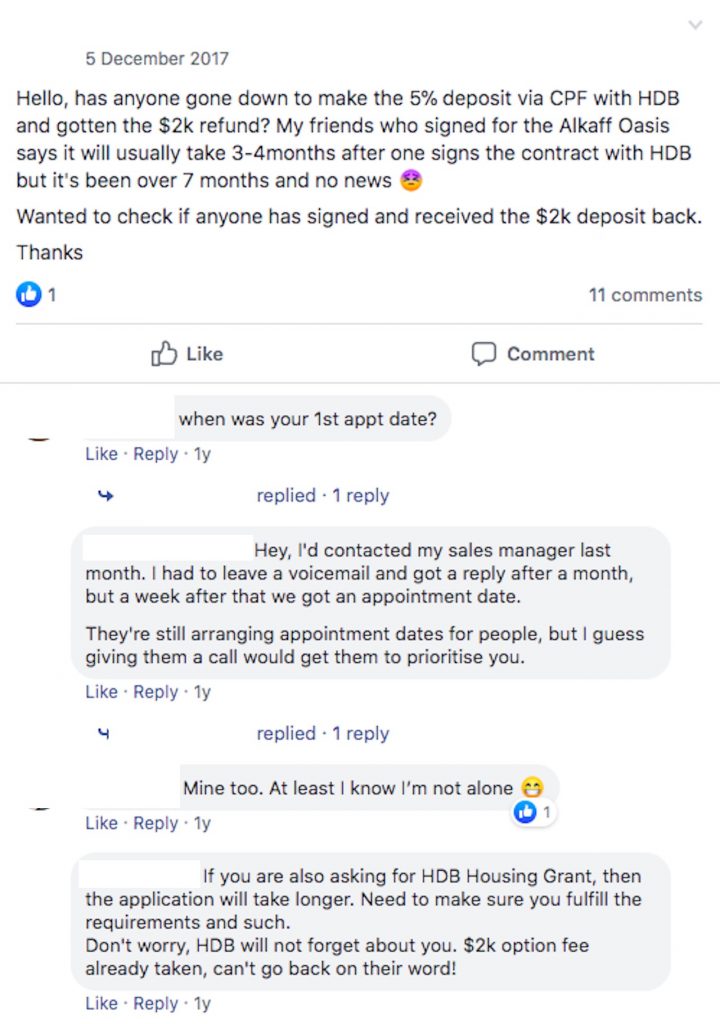

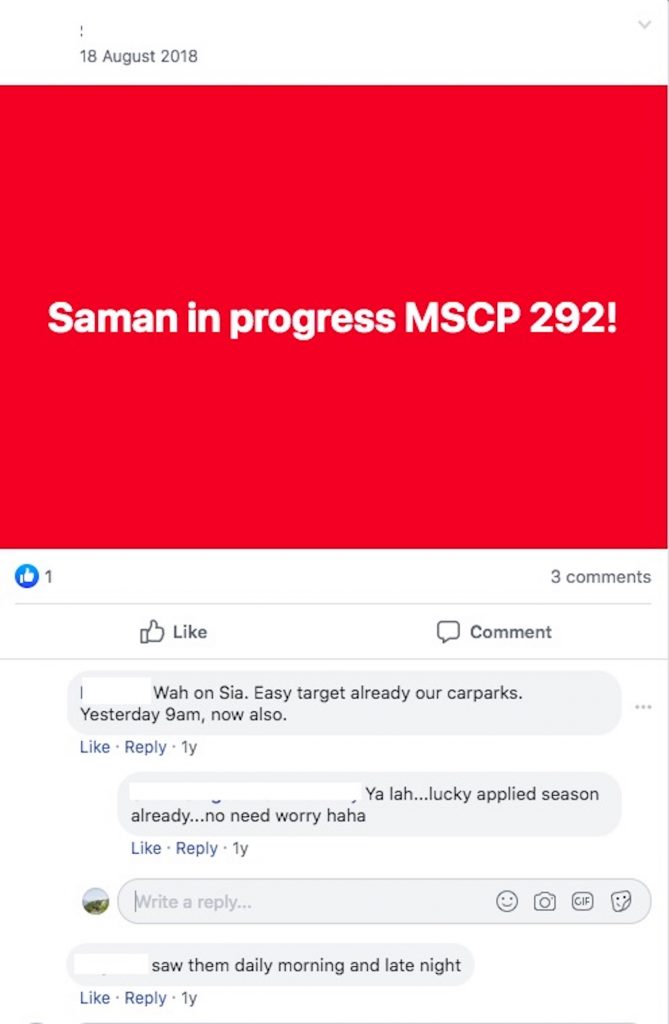

Finally, living in a BTO project that has a BTO Facebook group seems to necessitate being on your best behaviour all the time, lest you get called out for not adhering to living according to someone else’s standards. In the few screenshots that I’ve received from friends who are part of their BTO Facebook groups, you could get put on blast for anything, from parking at the loading bay to having your kids taking another resident’s e-scooter at the coffee shop.

To this effect, a BTO Facebook group is the realisation of STOMP’s nightmare surveillance state.

Nonetheless, journalism is about keeping an open mind. To find out what exactly draws residents to join these Facebook groups without a gun to their heads, I get myself accepted into a few private BTO Facebook groups that are supposedly open to residents only. (I can only hope they have tighter security around their estate.)

Residents provide each other with the best deals for renovation and interior design, highlighting the occasional helpfulness in these BTO Facebook groups.

Still, I am thoroughly drained by the utter banality, and now even more determined never to live in a BTO estate.

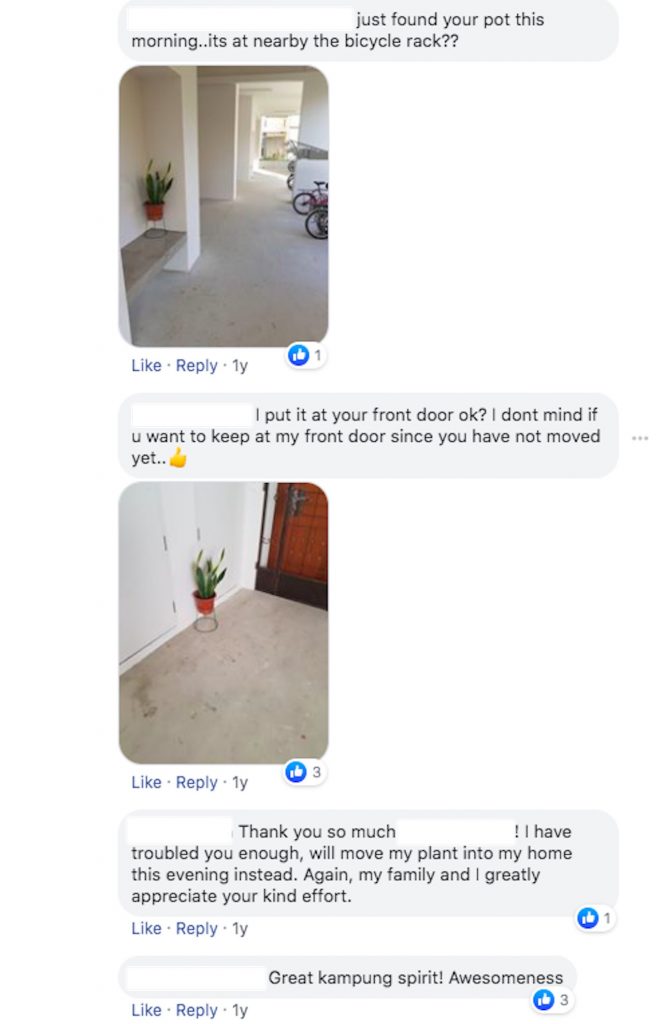

But beneath the blatant advertisements for renovation and interior design services, the human element shines through.

Just when I think my unbridled excitement from being a fly on the wall to curious neighbourly relations has been misplaced, my friends living in BTOs ‘reassure’ me that drama does exist. But this mostly crops up in the Telegram and WhatsApp chats created by members of the Facebook group.

Yes, on top of Facebook groups, these housing estates have also created personal chat groups.

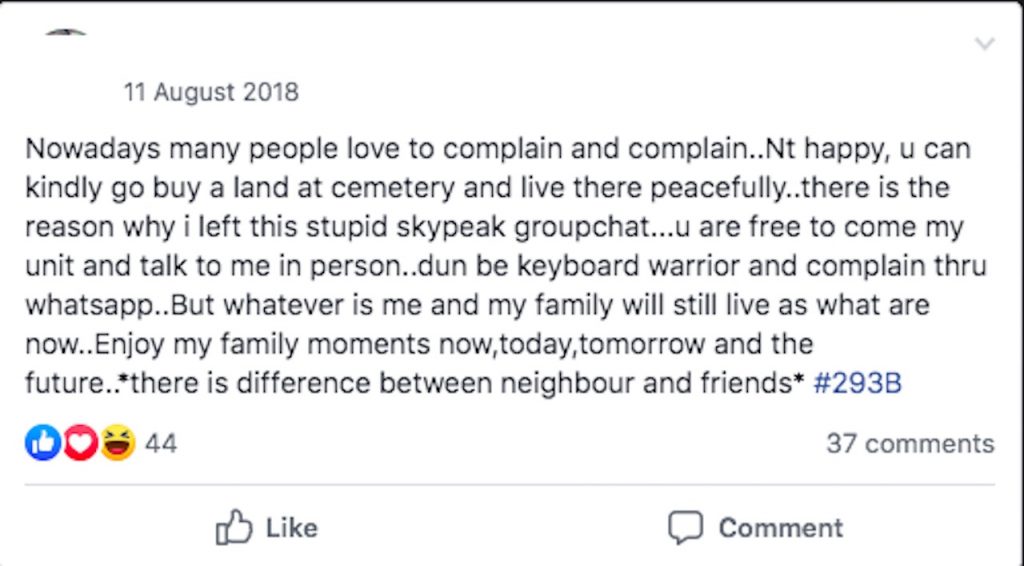

Then I chance upon the single BTO Facebook group that manages to entertain me to no end: Skypeak @ Bukit Batok (For Residents ONLY). The estate is within walking distance from my home, so I figure I should check out its corresponding Facebook group. Frankly, I don’t expect anything because my fellow Bukit Batok residents are not known for melodrama.

But after 29 years of living in Bukit Batok, I realise this batch of ‘new residents’ could single-handedly rejuvenate my sleepy estate after all.

“There is the reason why I left this stupid Skypeak groupchat… U are free to come my unit and talk to me in person.. Dun be keyboard warrior and complain thru whatsapp.. But whatever is me and my family will still live as what are now,” he writes.

“There is difference between neighbour and friends.”

His thread receives a sizeable number of reactions and supporters in the comments section, making my day with the exact degree of snark I’d been hoping to see when I first started researching this story.

Finally pleased with my haul, like an auntie at the wet market who’s gotten her fair share of gossip, I leave these groups just as quietly as I’d entered.

After the last few weeks, I’m convinced the BTO Facebook group essentially encapsulates what kampung spirit used to be.

According to our current idealised state narrative, kampung spirit is understood as “camaraderie, community spirit, social cohesion, a willingness to help others, and above all, neighbourliness”. The idea of this intangible Singaporean value “harkens back to a golden age in our history when every door was open, our neighbours more neighbourly, and the average Singaporean a kinder, more generous soul”.

This, however, is not the kind of kampung spirit that’s present in BTO Facebook groups. Neither would it be realistic to expect the romanticised version of kampung spirit to exist at all.

In all the BTO Facebook groups where I am a ‘resident’ for a few weeks, I experience the kind of solidarity that would only be possible among strangers; that requires little to no knowledge about each other. Once you know someone well enough to realise their flaws, it’s hard to accept them wholeheartedly, never mind if they are merely neighbours.

In these groups, it’s common to see strangers chatting as if they’ve known each other for years, when they might be discussing something as trivial as an activity organised by the Residents Corner.

Yet, there is also the sense that these BTO communities understand kampung spirit is not about singing kumbaya and pretending that living in such close proximity with people of different backgrounds, races, nationalities, and upbringings will be rainbows and butterflies.

The truth is neighbourly relations are inherently messy. Often, these relationships toe the fine line between tolerance and acceptance; one can be petty and helpful at the same time. Not everyone will love everyone else—and it’s completely normal.

If anything, the politics of BTO Facebook groups are a reminder that kampung spirit is not about ignoring the imperfections or sidestepping the disputes. It’s about confronting these quarrels—even if it lands you in the courts—and realising that the most underrated and precious part of a neighbourhood are its people and their relationships with each other.