Cover illustration and all other artwork by Dan Wong and Kimberly Teo of A Good Citizen, except where otherwise stated.

In a field as dicey and subjective as emotions, crying in public draws a rare unanimous response: nobody likes it.

To be clear, not all tears are created equal. There are a handful of situations where crying openly is socially acceptable, or at the very least, less mortifying—usually because tears are expected to begin with, or the trigger for them is evident. For instance, bereaved weeping virtually never invites judgement, while crying into your popcorn in a darkened cinema hall is sometimes a communal experience.

This piece is not about those kinds of public crying. If tears don’t seem out of place in a situation, and you can anticipate or arm yourself against them, it doesn’t count.

I’m talking about those moments of impromptu sobbing we’ve all encountered, whether as the person doing the crying or the person who stumbles across the crier: welling up in the loo during an intensely stressful day at work, or the time that song came on the radio and sent memories of your ex gushing to the surface.

It happens. We’ve all been there or know someone who has. So why are we still so flustered by it?

According to Dr. Ad Vingerhoets, a professor of Social and Behavioural Sciences at Tilburg University who studies crying, emotional tears (as opposed to basal or physical tears) are a result of various biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors.

In theory, anything could set us off: the first 10 minutes of Up, a bad performance review, or coming home after a 12-hour day to realise you left your keys at work. According to Dr. Vingerhoets, however, the two most consistent triggers for adult tears are a) feelings of helplessness and powerlessness, and b) separation and loss.

Moreover, we take issue with crying in public because it violates ‘display rules’, implicit or explicit rules that all cultures have governing expression and behaviour. In other words, there are situations where expressiveness is expected, and others where it’s expected to be moderated.

In a local context, our discomfort with crying in public is part of our greater cultural aversion to displays of strong emotion. Like any social norm, the parameters of this are hard to pin down; emoting to a certain degree is generally acceptable (even expected) in certain situations. But crying in public—showing ‘too much’ emotion—spills over into ‘inappropriate’ territory.

First, it’s an open display of weakness (ie. it breaks the display rule about conducting oneself with a certain degree of dignity, or keeping ‘face’). Second, to cry in public suggests a loss of self-control, a failure of mind over body. Together, these contribute to a third failing—that of the crier to stay in sync with the communal mood of their surroundings.

It’s not an issue if everyone is in tears; it’s a problem if only one person is.

These can lead to crying in public being viewed unfavourably, either as attention-seeking behaviour (it’s not enough that you couldn’t get a grip, but now you want everyone to know?!), or, more cynically, as downright manipulative—a calculated move by someone looking to gain sympathy points.

Both are strange conclusions. Accusations of crocodile tears only make sense when the crier has an interest in managing their public image (e.g. politicians and celebrities crying on camera), or where we have reason to believe they want something from us. The stranger quietly weeping into her phone on the MRT, however, has no reason to massage your opinion of her. Public criers ask nothing of those who come across them; they would rather not be seen in the first place.

That last point, broadly speaking, informed my original view: that we don’t want to be seen crying in public because it shows us in a state of vulnerability—arguably, at our most unguarded.

Most people I spoke with felt similarly. After all, being caught with your guard down and feelings on full display is a sight usually reserved only for our closest friends and family (if they even get to see this at all). To this end, some online literature about crying in public casts it as a radical act of vulnerability; an empowering one, even.

But on further reflection, I’m not sure I agree, and not just because there are better ways of getting comfortable with ~feelings~ than blubbering openly.

Of the countless times I’ve cried in public, none were pleasant (though many were funny in hindsight). But equally, none of them made me feel as raw and exposed as I did in some private moments: having the ‘what are we’ conversation with someone I was seeing; telling my parents I didn’t want to pursue the career they’d hoped for; even the first real fight of any relationship, when you are convinced your partner has finally seen the crazy person you are and is going to make a run for it.

All these felt like dragging sandpaper across my heart, over and over again, and then rubbing salt in the gashes. No time I cried in public, not even the epic post-breakup meltdown when I curled up in a ball and sobbed in the middle of the pavement, came remotely close.

Vulnerability isn’t just about opening up; its cornerstone is the real possibility of loss. We risk much less shedding a few tears in front of strangers, than lowering our defences before those we trust.

So is our discomfort with weeping in public—whether as crier or observer—really so warranted? As someone who’s done it more times than I can remember, I honestly don’t think so.

Of course, you could argue that I’m just trying to make myself feel better about my hyperabundant feelings. But one thing that stands out to me about crying in public, despite the fear and discomfort we feel towards it, is how ordinary an experience it is.

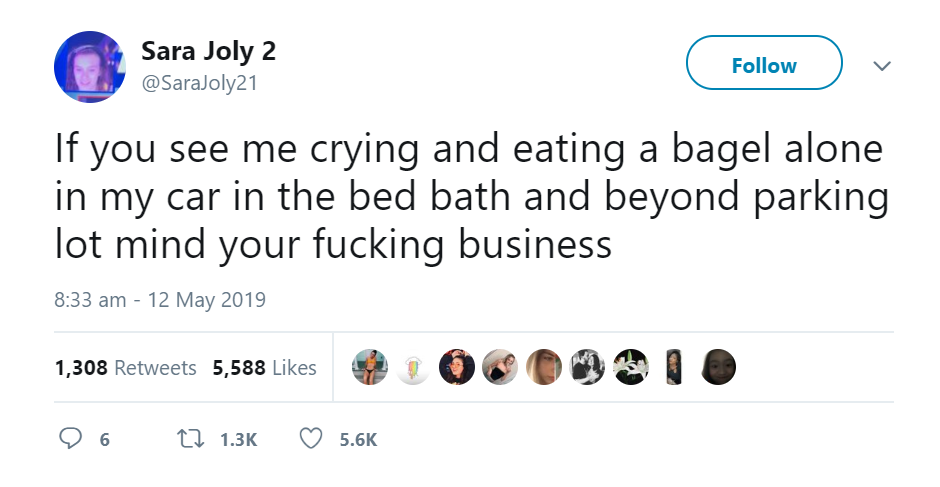

We don’t like to acknowledge it, but getting teary in public happens quite a bit, and for all sorts of reasons. While crowd-sourcing anecdotes off social media, several people ‘fessed up to their own experiences with weeping in public. A schoolmate wrote in about tearing up while reading a book on the MRT; another friend told me about a fight with her girlfriend over dinner which spiralled very dramatically. One guy sent me a link to a song with a time-stamp for the exact point which makes him tear up.

Over at Rice HQ, Grace gamely spilled (pun not intended) about crying into her cai fan during a fraught period at work. And I’ve wept in public for all sorts of reasons, from run-of-the-mill work stress to absurdly minor ones (like reading about the last words of NASA’s Opportunity Rover).

Crying, in essence, is a coping mechanism. Life happened, and we just happened to have a human response to it while around other human beings.

Viewed this way, it’s odd that our mortification often ends up superseding our original reason for crying (or the cathartic power of letting it out). We will ourselves to get it together, not because we’ve addressed the issue that made us so upset, but because we don’t want to make fools of ourselves. And long after we’ve stopped shedding tears, it’s the embarrassment that stays, and ends up defining our memory of the incident.

This is pretty backwards, whichever way you look at it. If you’re crying because something significant happened, surely that reason should have the greater impact. And if you’ve welled up for a relatively trivial reason, why exacerbate things with unnecessary shame?

We think of crying in public as unnecessarily, excessively emotional. But the same could be said about our attitudes towards it.

Returning to Dr. Vingerhoerts for a moment, his hypothesis is that humans developed emotional tears as a social trigger for empathy. According to him, welling up is a cognitive and physiological response, a signal to say we need support or encourage the de-escalation of conflict.

In my inexpert opinion, however, this gets complicated where crying in public is concerned. First, public criers generally don’t want to be seen crying in public (or to be crying to begin with). Depending on the intensity of your weeping, your eyes swell up, and your nose gets sore and stuffy; you become red and blotchy and desperately unattractive. Crying never looks good unless you are a woman in a Renaissance painting.

We might technically desire support, in the broader scheme of things, but few public criers actually want to be disturbed in the act of shedding tears itself. As Melissa Febos succinctly described in her own essay about crying in public, “…[I]t’s not that I want apathy, just privacy. To be noticed, but not interrupted.”

Second, crying in public rarely elicits a sympathetic response. In fact, most of us would probably back away slowly, unsure of how to deal with the situation. Sometimes, it even draws criticism and judgement.

Why are we so bad at dealing with something so human? Absent any context, are we less upset about seeing another person in distress, than upset with them for making us feel uncomfortable? Do we accuse people crying in public of narcissism while making it entirely about us?

How we respond to someone crying in public says much more about us than it does about the crier. In this, amidst my many public meltdowns, one memory stands out.

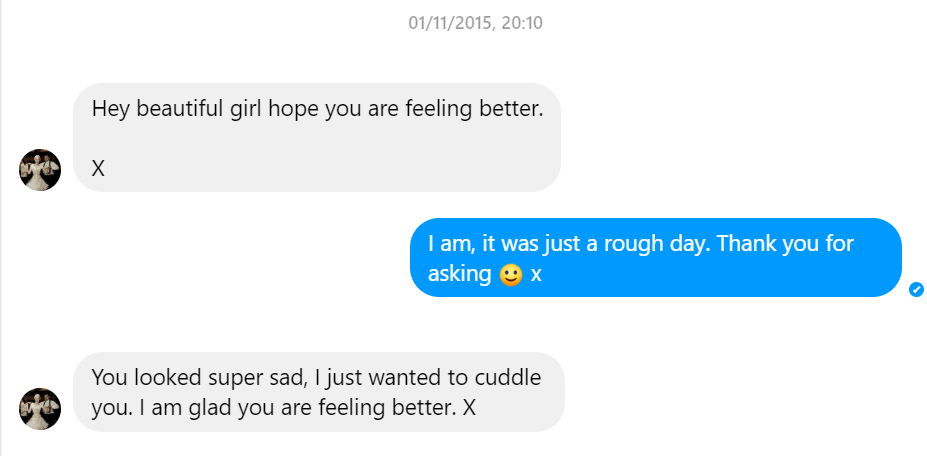

A few years ago, I found myself in tears on the staircase of a club at 1:00 AM, tipsy and overwrought after a fight with my boyfriend. Naturally, this had to be over the phone and while I was dressed up as a cat for Halloween.

As my whiskers melted off my face, a man I knew—not particularly well, just as a casual acquaintance—passed me on the steps. There was no way I could hide my face, and I was too far past caring to try to. He didn’t ask if I was okay, but his features twisted in a grimace of sympathy as he met my gaze. And then he walked on and out and left me to it.

The next day, I received a message from him:

Speaking personally, this is as ideal a response as it gets.

I’ve mellowed a lot in the last couple of years—I didn’t even well up at Avengers: Endgame, or Tyrion and Jaime’s emotional goodbye during Game of Thrones—but the one thing that undoes me is tenderness. Unexpected kindness is dangerously disarming; even if I’m not acutely upset, just low-level blue, an innocent question like “Are you all right?” will generate instant waterworks.

Had my friend stopped me on the stairs, I would probably have sobbed harder, and we would both have been more distressed for it. But he somehow sensed that the wisest course of action—and what I really wanted—was to leave me to my own devices, despite his impulse to intervene. Respecting my wishes, and taking the time and thought to check in afterwards, was as good as an example of empathy as it comes.

Crying in public doesn’t have to be fraught with embarrassment and awkwardness. It doesn’t have to invite scepticism or fear or judgement. The roots of that magic word, empathy, literally mean to travel into feeling; someone else’s, mainly, but the metaphor applies just as well to our own.

Sometimes we undertake this trip in the open. Sometimes we stay there briefly. But life is full of detours, and none of them, however damp, ever stopped it from going on.

Writing this made me want to weep with frustration. How did it make you feel? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.