Names of practising Jehovah’s Witnesses have been changed out of respect for their privacy.

When Alvin Phua was 10, his mother opened the door to strangers who spoke fluent English, thinking they could be tuition teachers for her son’s weak command of the language.

They were, in fact, Jehovah’s Witnesses (JW), and that was the day mother and son joined the community.

For the next eight years, Alvin was a devout JW. Not only was he unconcerned that the Singapore government had de-registered and banned the activities of the religion since 1972, he was also pleased that they did.

“You feel like part of a secret gang. Isn’t that fun? Everybody takes pride in some kind of identity. Knowing the main reason for the ban was because JWs refuse to bear arms in military service made their pitch even more attractive. As a kid, you want to be a superhero and save the world.”

JWs also refuse to salute the flag or swear oaths of allegiance to the state, a practice linked to respecting Jehovah (their term for God) as the utmost power.

But Alvin, who is 43 this year, always knew there was someone more important: his mother. At the time of his enlistment, she was no longer a JW and threatened to disown him if he refused to serve.

“I told God: ‘I know I’m supposed to love you more than mom but I cannot lah. I’m supposed to be honest about it. If that makes me lose my ticket to paradise, so be it’,” he shrugs. His easygoing charm made him a good preacher once upon a time.

Though the first seeds of doubt were already sown, it would take him six more years to fully leave his religion. He was 26 when he finally embraced atheism.

Today, he talks about his former religion as a matter of fact, “Usually, JWs are incredibly nice and peaceful people, which helps their cause. You won’t see megachurch kind of people there.”

Then, his voice softens: “I still love the notion of not bearing arms, but I’m not against national service. I’m just against the JW principle for not doing it.”

This cynicism means that JWs usually have their work cut out for them. Most of us only know JWs from their door-to-door preaching, or from rumours we hear from friends and family. Our experiences with JWs rarely stray beyond these confines, and we often associate them with cult-like behaviour in an attempt to form our own understanding of the religion.

All the same, I speak with practising JWs to discover if they do indeed subscribe to strange and extreme ideas.

While she’s a typical 20-something in Singapore, she is also a Jehovah’s Witness.

Michelle admits that she may not be able to provide me with the answers I want, because she doesn’t feel “worthy or ready” to dedicate her life to Jehovah yet.

“I agree with the values, but sometimes it’s hard to believe in something you don’t see. I’ve been questioning a lot of things, and haven’t been going to church as much as I should. Life happens.”

There are also many grey areas that she struggles with. For one, she doesn’t want to limit herself to dating only within the JW community but understands that her wishes contradict her religion’s teachings.

We touch on the LGBT community and I expect her to avoid the controversial topic. But she cautiously broaches her subsequent questions: “Actually, what do you think of Pink Dot? It’s easy for me because I’m straight. But what about a gay person? How do they manage if they want to be in a religion?”

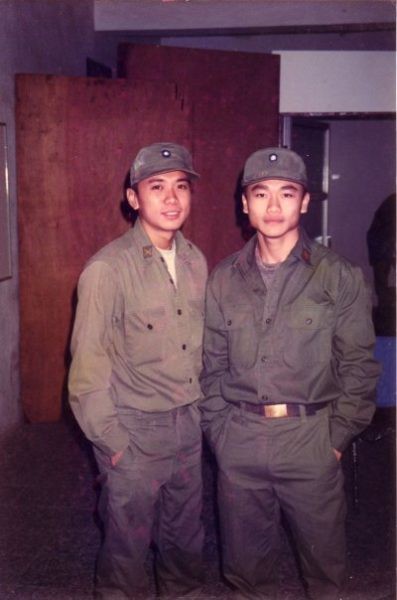

Because the government does not recognise conscientious objection as a legal reason for refusing National Service (NS), they are sentenced to three years in the SAF detention barracks, albeit separate from other conscription offenders.

A military prosecutor shares: “During Court Martials (the military equivalent of a criminal trial), I would ask the accused fixed questions, such as, ‘Are you aware that it is an offence not to swear allegiance to Singapore?’ They would reply with bible verses. After a guilty verdict is entered, his family and church members, who usually come to show support, clap for him. This is like a rite of passage for JWs.”

He also admires their conviction, though he wonders how much of it comes from the pressure JWs receive from their community. “After all, if every male JW goes through this, that puts pressure on the young boys to do the same, whether they want to or not.”

Speaking to him, I get the sense that most who have interacted with the JW community are respectful yet apprehensive of their practices. It doesn’t help that the lack of public information only perpetuates urban legends about the religion.

For example, a friend’s dad shared that, before JWs were sent to detention barracks, those who objected to carrying arms would be forced to march carrying broomsticks instead. Nobody can confirm this myth, but stories like this involuntarily form a caricature of JWs in our minds.

Understandably, JWs are also notoriously private and wary individuals.

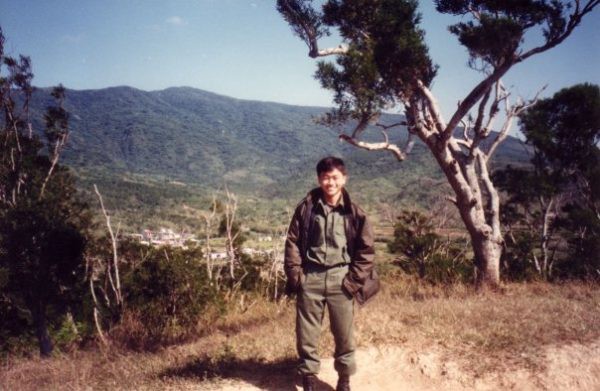

On first impression, he is open, mild-mannered and earnest. It only takes a few minutes for him to reveal an infectious brand of self-awareness and humour.

“We are normal humans,” he deadpans. “My wife and I fight, like any couple. We also want to have fun like you do. You want to watch the latest movie? We also want.”

He is also surprisingly empathetic towards a body that denies him the freedom to worship his God. When he needed to enlist, Jonathan didn’t want to “run away from services that [he] felt citizens should perform”, so he asked for “alternative services.” This meant gardening, doing laundry and cleaning offices.

“Singapore is a small nation. You need men to fight for the country. Authorities don’t have it easy either. They can’t please everyone. We need to be understanding to them too.”

So at 17, he chose to be a JW – but not before undergoing his own baptism of fire.

“When I was studying the bible, my parents forbid me from playing basketball with my friends, who were more rowdy, as they were afraid I would be led astray. I love basketball so I felt left out. But I suppose that’s normal when you’re a teenager. If you’ve never felt that way, then you are really weird.”

As Jonathan tells me about the unspoken, unconditional brotherhood that exists within the JW community, the deep irony isn’t lost on me. He has found his place in a community that isn’t afforded its own place in Singaporean society.

To understand the general sentiment of the mainstream Christian community towards JWs, I speak to Reverend Aloysius Tan. He shares, “We embrace JWs with mutual respect, loving them as humans, but we will never agree with their strange and extreme teachings that contradict the Christian faith. Unfortunately we can’t debunk the myth that JW is a cult.”

I can’t help but wonder: how is the criticism towards JWs any different from those directed at equally divisive beliefs, such as the prosperity gospel? Can we ever fully accept those whose fundamental beliefs and values are starkly different from ours? Or does empathy have a limit?

Perhaps the perceived differences between humans are less about which God one prays to than about a far simpler truth: we use our own behaviour as the basis of how we judge others. In the process of researching this story, I find myself almost ashamed that I had arrogantly assumed my idea of normalcy was the ‘right’ one.

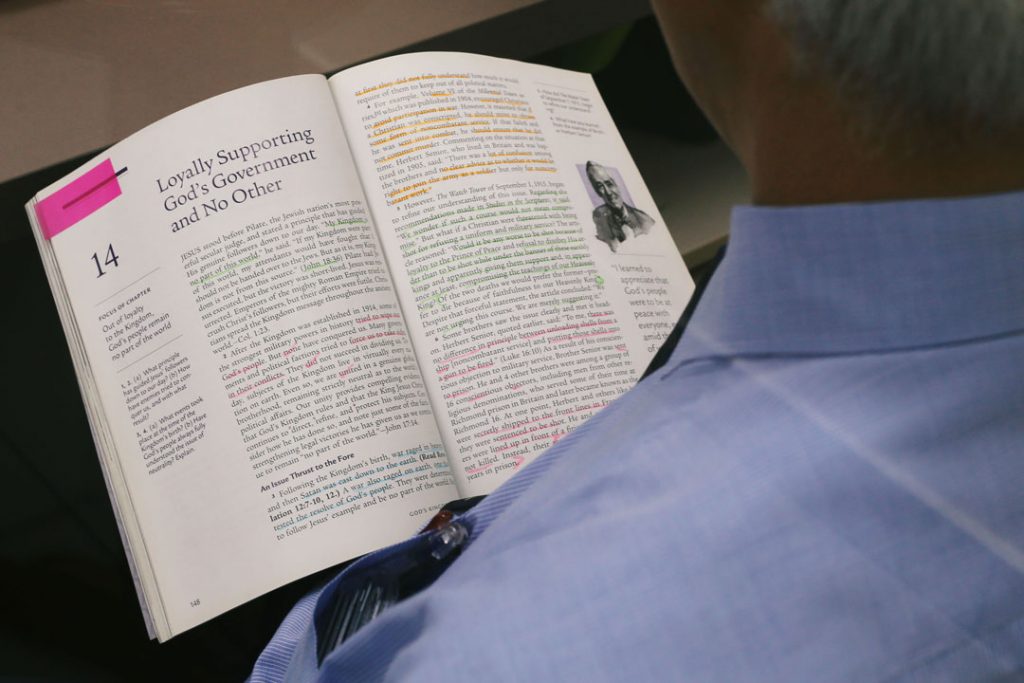

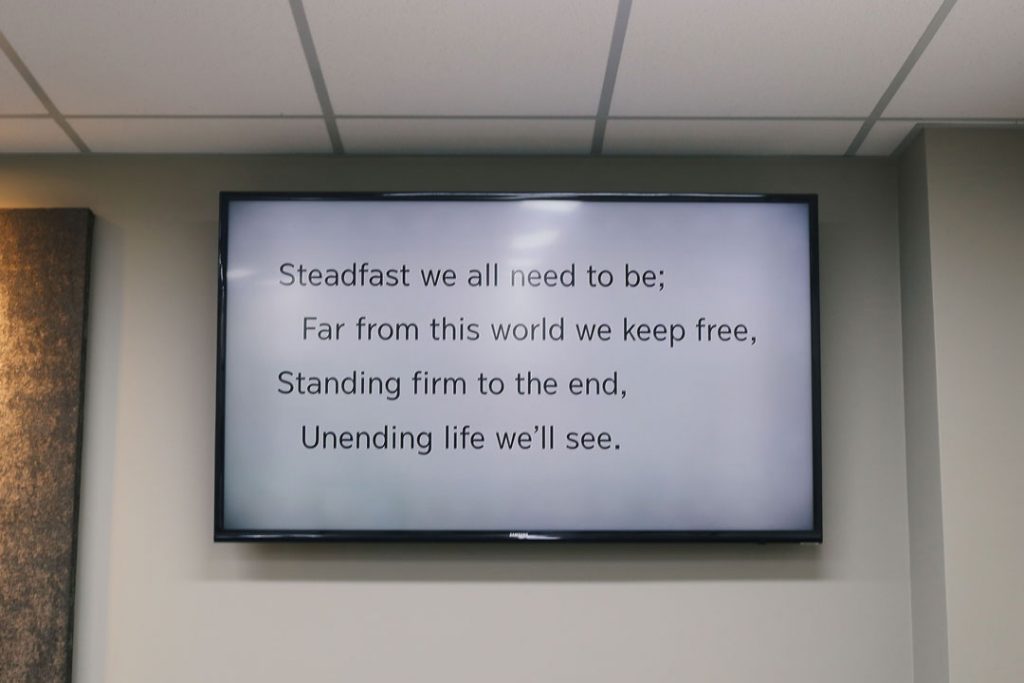

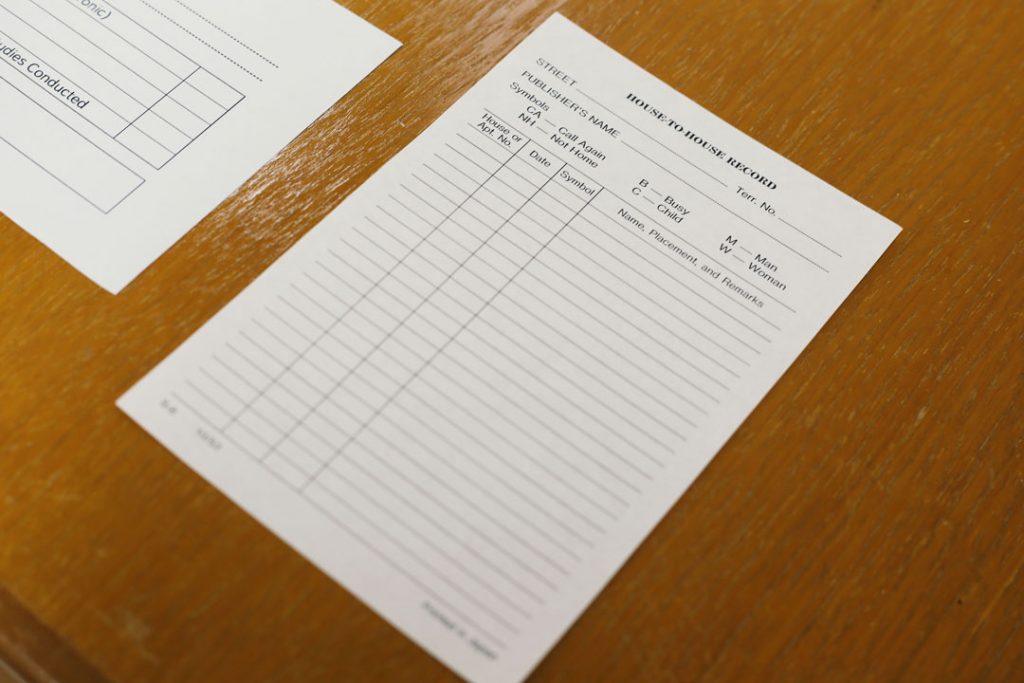

One such place is the newly built Kingdom Hall in Bukit Indah, which I visit for a Thursday night meeting. Each meeting typically lasts 1 hour and 45 minutes, and comprises about 50 members. They tell me several Singaporean JWs regularly make the trip across the causeway. There were also a few who moved to Malaysia for a few months to help with the construction of this Kingdom Hall.

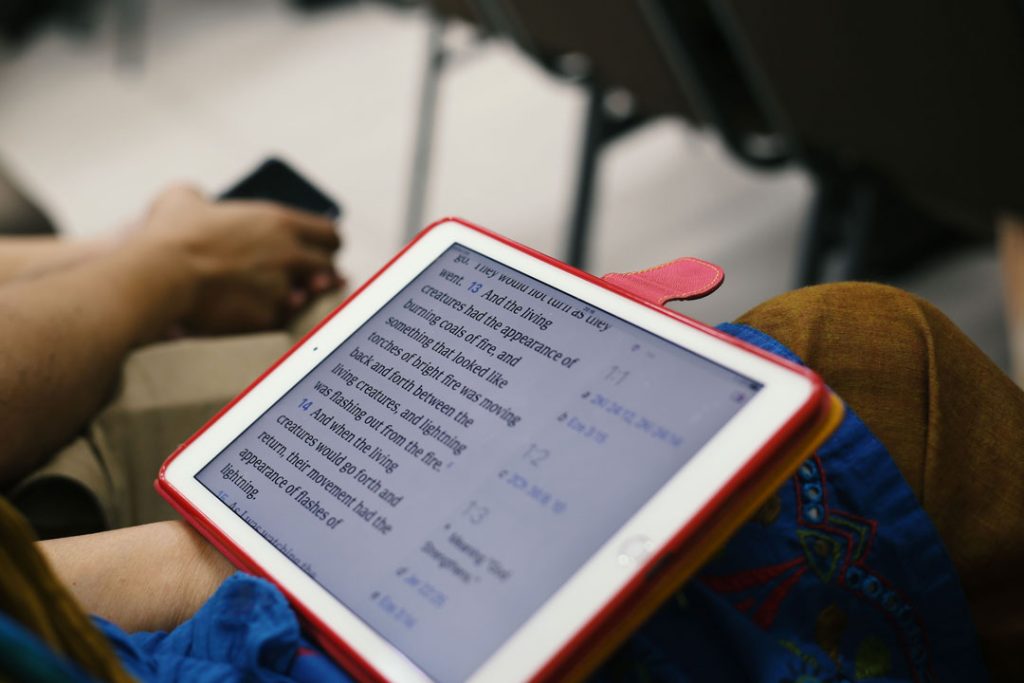

What strikes me most is how remarkably friendly and warm everyone is, an observation that echoes the sentiments of Alvin and Jonathan. Everyone who notices my unfamiliar face approaches to say hi. I have never felt so welcomed.

Meetings function like a university tutorial – members share their thoughts on real-world scenarios, tackling them from Jehovah’s point of view. At the end, I am pleasantly surprised by how intellectually stretched I feel.

“There are a lot of misconceptions that we don’t have the opportunity to clear. Some people even tell us to go to hell. But we are only human. Even if you don’t appreciate a message, you don’t have to be sarcastic, right? Luckily we’ve seen more open-minded people over the years,” Jonathan says.

More importantly, doesn’t subscribing to a religion you know is banned only welcome trouble and criticism?

He explains his stance simply: “People assume something that is banned is automatically dangerous and wrong. By that logic, gambling at a casino is not banned, but does it mean it’s okay to do that?”

Yet I was suitably underwhelmed to eventually find Jonathan, an ordinary man, sitting in my living room.

Now I think about how we fear what we don’t know, how the unfamiliar is usually scarier in our minds than in reality, and how the best way to dispel unfounded fear is to confront it head on. In this political climate, my realisation feels exceptionally relevant.

Just before we part ways, I jokingly ask if Jehovah would smite me for writing something terrible about their religion.

“To be honest, whatever you write won’t bother us. If we were so easily bothered, we’d have stopped practising over 40 years ago. Don’t worry, we won’t go ‘hope this woman get it ah!’ We won’t curse and swear,” Jonathan laughs.

“We can’t use vulgarities anyway.”