I’ve never entered Tong Mern Sern Antiques Arts & Crafts, despite passing it and photographing its famous sign countless times. Located at 51 Craig Road, the yellow banner at its storefront boldly states: “We buy junk and sell antiques. Some fools buy, some fools sell.”

The store had always struck me as woefully intimidating, because I didn’t know whether I’d feel satisfied indulging my curiosity or if it would leave me wanting more, like sneaking a glance at a partner’s text messages—a thought that attracted and repelled me at once.

But I am lucky that I get paid to be a busybody.

In my 29th year, I finally visited Tong Mern Sern one morning while taking a walk around the Tanjong Pagar neighbourhood before work. The owner, Keng Ah Wong (more affectionately known as Keng), is brusque at first. He asks what I’m looking for. I smile sheepishly: nothing, Uncle, just looking.

We end up chatting for 15 minutes since there’s no one else in his store, during which my attention is frequently broken by a thingamabob that catches my eye, and then another, and then another. Before I leave, he gives me a silver antique police whistle for free. I promise him I’ll be back to hear more stories, and he nods, as though he’s heard this commitment before.

But life gets in the way, and two months pass before I return. This time, however, I dedicate two days to perusing his knick-knacks and listening to his stories.

His daughter, Clara Keng, whom I meet on my second day in the store, shares that when her father recently fell ill, his main concern was Tong Mern Sern, having spent decades building up.

In order to give her father peace of mind, along with the time and space to recover properly, she quit the corporate job that she’d held for six years to work for the family business.

As a full-time employee of the antique store, she sees all sorts of customers, from regular collectors to people looking for event props and those opening themed bars and restaurants. But the problem arises when customers don’t know what they want, such as broadly requesting “anything from the ’70s or ‘80s” without specifying the purpose of their purchase.

For example, a stool could cost $50—an amount that might get you five stools from IKEA for the entire family, while an ornate Peranakan table could fetch $3,000 to $5,000.

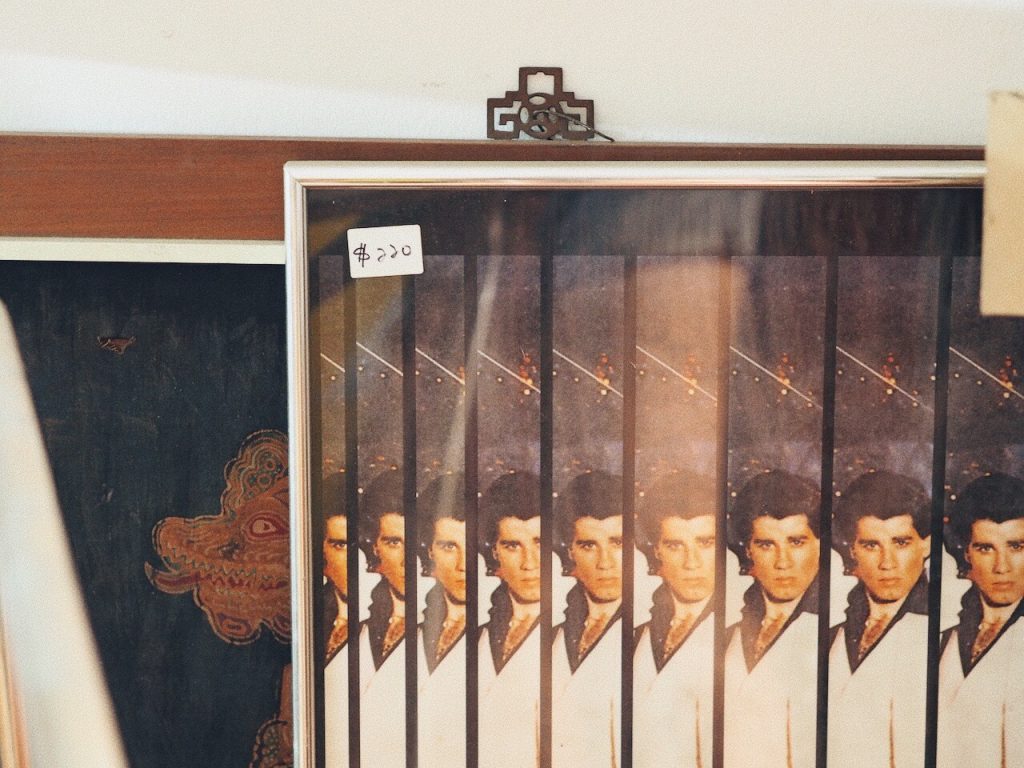

It’s easy to get caught up in the never-ending hodgepodge of curios that line the walls, floors, and even ceilings, but if my memory serves me right, I also notice a collection of porcelain spoons that cost at least $20 each.

Clara admits that the relatively high prices on antique items often make people believe this business is “easy money”. They don’t see the hidden costs involved in making things work, such as building lifelong relationships with customers-turned-friends, and repairing broken items that long-term customers might donate for free.

In the case of the latter, Clara says that people only see the final mark-up when the item is ready for sale. For instance, if the Kengs have bought an item at $50 and sell it at $200, people might not realise this extra cost comes from refurbishing it.

What’s the most memorable item in the store? I ask, not expecting an answer. After all, I certainly couldn’t pick my favourite from among the thousands of bric-a-brac.

But there is one, Clara recalls. Her father spent three years fully restoring an old music box that he’d bought from Malaysia. Every night, he’d tinker with its spare parts, changing its corroded metal disk.

Such spare parts are hard to find these days, resulting in a waning ‘repair’ mindset among the present generation, including her own friends. People are inclined to throw away broken or damaged goods rather than fix them—an unfortunate metaphor for our relationships with people and objects.

I ask several times if he’s thought about selling off his store to a wealthy customer, or living out his golden years without working.

“If you love your job, you will work. I enjoy my job. I don’t need to worry about rent also. Today no business, very quiet, but it’s okay,” he shares every time.

Part of this passion stems from being an honest businessman. He “doesn’t like to cheat customers”. When an object is chipped, he would alert the customer to its defects before selling the item so they are aware of its faults. This transparency allows both parties to remain satisfied with the transaction.

Keng’s candour seems to have been inherited by his daughter. Clara admits that there might not be “CPF” or “child subsidies” in this job, but she does this because no one will do it otherwise.

“Do I hate it? Do I love it? No and no. I take it one day at a time until this store really has to close,” she says, matter-of-factly.

Having grown up around antiques her whole life, you could say that quitting the corporate world for the store was like coming home. When she was younger, the pieces of furniture at home, such as the study table, often comprised antique items from the store. Anytime a customer wanted to purchase an item from her home, her dad would sell it off, leaving the family with entirely new furniture every few months.

For all the impermanence of her childhood, there is a sense of resolute duty in her voice regarding her desire to continue her father’s business.

“As a child, you see that not many people, like my friends, understand what my family does. Only when you get older do you understand,” she smiles.

The three-storey shophouse is a labyrinth of everything and anything you can possibly imagine, including some broken goods that seem to be in the process of repair. Every time I think I’ve seen everything, I lift a box or push aside a basket to reveal more weird and wonderful artefacts.

On both the days I’m there, I leave my backpack on the floor at the entrance, lest I accidentally knock over precariously balanced paraphernalia.

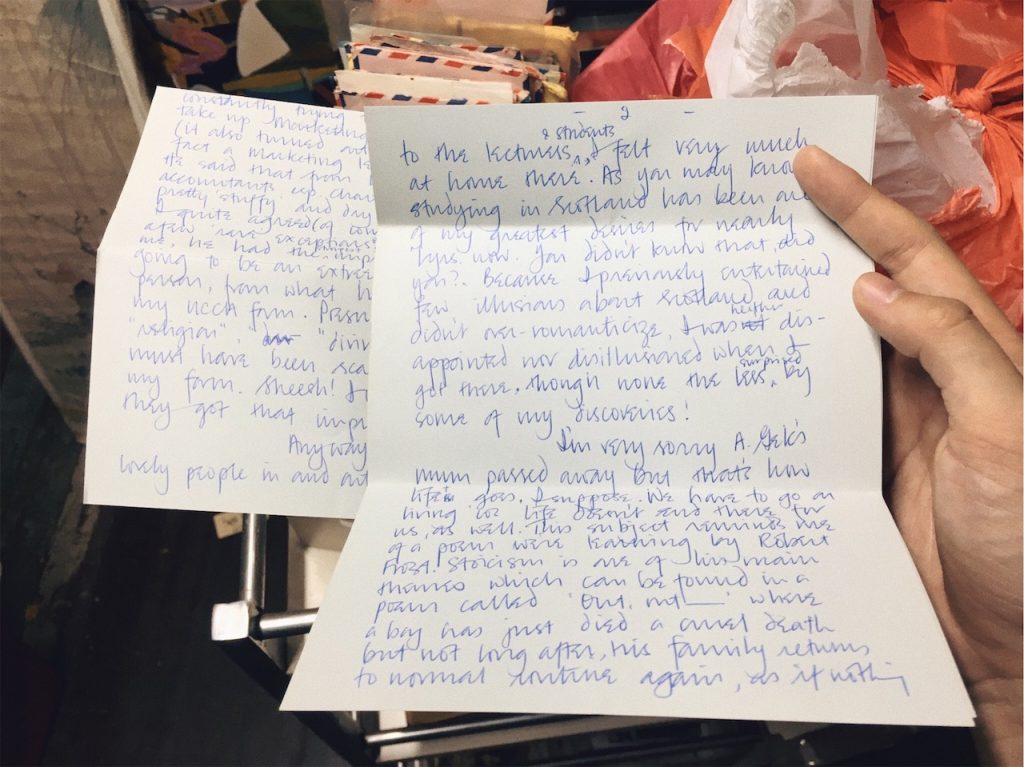

A quick google search reveals that Mdm Irene was an Indonesian who passed away five years ago. Oddly, this fascinates me even further, and I spend the next 30 minutes deep-diving into her letters, which I suspect were donated to the store along with her other belongings after she passed away.

The back of the second storey resembles a spacious ‘balcony’ of sorts. It looks out at The Pinnacle@Duxton, where Keng and his wife, as well as Clara, live. In this airy space, there is also a messy work station, where one of Keng’s employees-slash-friends tinkers away at broken objects.

As someone who absolutely loved D&T in school, this nifty little quiet space is a damn dream.

An open window allows the sunlight to stream in. As much as I’m not one to scare easily, it helps me fight off the heebie-jeebies.

Allowing others to walk around my living room, use my toilet, and hang out in my bedroom means granting them access to the private memories attached to every object at home. On my bed lies the pillow on which I’ve wiped my tears after every relationship ended. In the kitchen, the table has seen me through lonely lunches as a teenager after school, but also sleepless nights spent sending out resumes in desperation. At the back of the storeroom sit a few childhood toys that I won’t chuck because I’m not ready to confront the complicated feelings attached to them.

Even if I don’t talk about these memories, the mere presence of having someone in the space where my most personal belongings are kept can feel strangely intrusive.

There is simply not enough time in the world—and before this piece is due—to revel in the sheer mountain of deeply personal stories and histories attached to the most ordinary items at Tong Mern Sern. But this much I know: we are all tethered to our physical belongings through the meaning we ascribe them, long after they’ve left our possession.

Once upon a time, I read a story about our permanent relationship with certain inanimate objects. It involved a man whose ex-girlfriend had passed away. Years later, when he was packing up to move house, he noticed her bobby pin lodged between his floorboards under his bed and promptly had a breakdown.

I don’t have a dead ex, but the story left me reeling from emotion. I deeply related to the notion that the objects we own end up owning us through our memories and experiences.

Likewise, in the three floors of gadgets and gizmos aplenty, whozits and whatzits galore at Tong Mern Sern, it’s convenient to imagine the lives of strangers from their objects. But the stories we tell ourselves about their lives are merely a projection of our own.

In the end, what we see in a dusty film camera or a collection of old magazines reflects the things we need to confront about our own lives.

Tong Mern Sern Antiques Arts & Crafts is located at 51 Craig Road, Singapore 089689.

Have something to say about this story? Write in: community@ricemedia.co.