VICE said that “coronavirus could finally pop the influencer bubble.” WIRED said that “some influencers have watched with a growing sense of dread as the world collapses, taking their earning potential with it.” Bloomberg said that for influencers, the “picture isn’t pretty.”

What I’ve found out has been very different—it’s actually a great time for their industry.

I came to this conclusion after a series of inquiries that started on April 19, when Saffron Sharpe posted a photo of the sky.

To me at least, this modest yet bewildering sky picture was pivotal. It marked the beginning of a new era in which we are no longer bombarded with posts about what to buy and where to get it.

Simply put, many of us need to save right now, and promoting consumerism can seem irresponsible. Many have lost their jobs, taken pay cuts, or been forced to go on unpaid leave. And for those who still have their jobs, they have no reason to buy clothes, or are worried about their financial security with the upcoming recession.

“Right now, I’m trying not to be flashy with the products that I own. Everyone’s going through a tough period,” Saffron Sharpe told me.

“It’s about being sensitive that people come from different social-economic standings.”

Camira Asrori, a fashion influencer who owns a clothing brand by the same name, said that “it’s a little tone deaf when influencers keep posting photos from their archives. It doesn’t connect with their audience because it’s obviously from before, when you could be outside without a mask.”

While both Camira and Saffron have had to change the way they create content, in order to reflect present times, neither see it as a bad thing at all—which is different from the narrative haters might be inclined to believe.

In fact, they seemed pretty excited about right now.

Financially, they have definitely taken a hit. Both Camira and Saffron said that the majority of their campaigns have been postponed or cancelled.

“I have zero income right now,” Camira admitted. But finances aside, the number of people online during this time signals huge potential for growth.

After this lockdown, “everyone will be out, reconnecting with their friends, and clubbing. We’ll never have that engagement again,” Saffron said.

As well as more captive eyeballs, influencers now have a new kind of freedom too. Usually, they are too busy keeping up with #ads that they don’t get the chance to get creative with their feeds.

”To work with big brands you need to maintain a certain image on your feed. But now I don’t care about that, I can do whatever I want,” Camira said.

“What I have realised is that most influencers are not creatives,” Camira shared.

“They are attractive and know how to take nice photos, so they aren’t doing much now—and it’s fine. But for creatives like me, we need to keep creating, because that’s how we channel our energy.”

Local influencer Salina Chai’s feed, for example, has remained largely unchanged. Designer clothes and photos outside without a mask still dominate her grid. She tried to switch it up on her Instagram story one day with a light hearted Q+A—but when asked what her bucket list was, she responded with a list of brands she wants to work with.

Quite underwhelming.

“One thing on my bucket list is to go cliff diving,” Camira told me when I asked her about this.

In contrast, is Salina’s personality just outright boring? Or is she just sticking to her branding and business strategy?

Whatever the answer, it only highlights with greater clarity the divide between ‘influencers’ and ‘content creators’. One exists for business purposes; the other exists as a platform for creativity and personal expression. There’s no wrong or right, but in times like these, audiences might finally become more critical about the content they actually want to see on Instagram.

“It’s 5 or 10 times harder to make content from home,” Camira said. While this might mean that content creation is more challenging than ever, it also means that those who succeed will really stand out from the competition.

At first, Camira struggled because: “I’ve been living at my grandparent’s house and I sleep in the same room as my brothers. The house is not aesthetic, so I was really frustrated.”

But Camira found a way to put these struggles forward in a relatable and tongue in cheek way when she posted her take on the viral ‘bored in the house’ challenge.

“I saw a lot of people doing the challenge, but they were all flexing their mansions,” Camira said.

“Why is no one doing it in a HDB, when the majority of us live in one? So I did it, and a lot of people related.”

“I realised that we do have a certain role to play in social discussions,” Saffron told me.

For example, she recently spoke up about the migrant worker issue in Singapore, and as the conversation developed, was able to “connect with my younger female audiences, especially about struggles with self-love and body image”.

In a way, this sums up what the role of the influencer should be. They help us make sense of our times in bite-size online content, whether by adapting international trends to our local landscape, or by making us feel like we have someone who relates to our daily struggles.

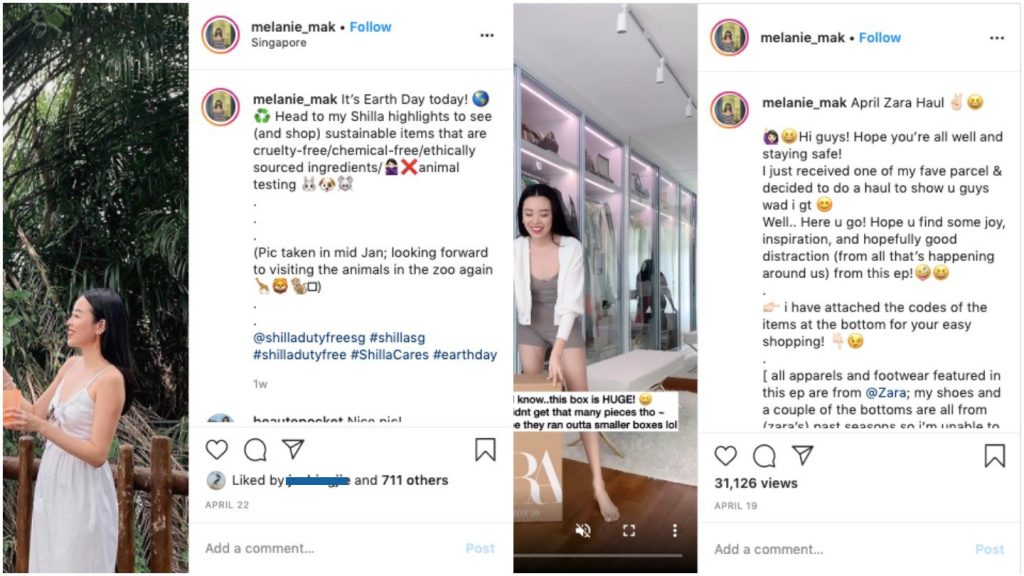

On April 22nd, local influencer Melanie Mak posted about buying sustainable products on earth day right after a video of a ‘Zara shop haul’. All this despite the fact that Zara is one of the biggest fast fashion brands on earth.

While Melanie’s inconsistency went largely unnoticed, local influencer Jamie Chua later stirred up controversy after posting an Instagram story that said she woke up from a nightmare in which “Indian workers” were “rushing into my house.”

The post was deemed insensitive, and even borderline racist, considering the vast majority of coronavirus cases in Singapore have spread within migrant worker dormitories. She has since apologised for the post, but both this incident and the one involving Melanie hint at the kind of tone-deaf content that audiences might eventually become less tolerant of.

But Camira said that “as long as you were real from the start, it’s fine.”

“I only work with brands that have the same values as me and I don’t promote fast fashion,” she added.

No doubt, being an influencer is good business, and consumers rely on influencers for product recommendations. But what this break from consumerism has done—for now—is given us a chance to re-assess the digital landscape, the roles everyone plays in it, and what we as consumers can demand from it.

We can hold brands accountable when they don’t align with our values, and we can do the same with the personalities we follow online. And hopefully, real and actual personalities will become the norm, rather than influencers whose feeds are really just billboards and lookbooks.

As consumers, we have the power to decide this.