Zeng Guo Yuan, more commonly known as the “Parrot Man”, might have his own Wikipedia page, but he has led a bloody sad life.

Where his nose used to be now lies a sore, crusty, and gaping hole. Down the middle, it’s divided by the cartilage that separates the nostrils.

Every day from about 10am till just after lunch, the 65-year-old tissue paper seller shuffles through the crowd at Geylang Serai Market in a white robe too long for his stocky stature, toting a large duffel bag clumsily slung around his shoulders.

Looking at him place tissue packet on table after table, no one would guess he used to live in a bungalow that contained rooms each the size of his current bedroom, kitchen and toilet combined.

While he now relies on the generosity of strangers to get by, the former philanthropist and businessman once earned enough to build a mosque in Bangladesh. In his heyday, he also ran his own acupuncture practice and served as President of the World Acupuncture Voluntary Organisation.

In our conversations, he often alludes to his ‘illustrious’ past, frequently name dropping ‘important people’, including former President of Singapore SR Nathan, late entrepreneur CK Tang, and current manager of Ngee Ann City Eric Chan.

These days, he is a shadow of his previous self.

According to him, doctors also cut his thyroid and salivary glands.

As a result, those who notice him for the first time often stare a second too long before looking away, brushing him off, or forking out loose change. No one directly asks what happened, although the morbid curiosity shows on their faces.

Soon after removing his nose, the cancer metastasised, leading to a removal of a part of his large intestine. He now goes around with a “shit bag”.

Few people would be able to survive the same series of unfortunate events without spiralling into debt or depression, both of which he has suffered. Even though he was referred to the Institute of Mental Health for his “not so good” mental condition since the accident, he calls depression “a state of mind”.

“I can look at my accident as a result of being unfortunate, because I’ve done something wrong, or as a tribulation. Or I can look at it from another angle; I can be grateful that God has saved me,” he says.

Since young, Mr Zeng has been religious. He claims to be both Muslim and a Jehovah’s Witness, but also uses stories of Jesus and Guanyin to preach about the benefits of religion. He genuinely feels “fortunate to be alive”, and displays an optimism that never comes off as a front for any deep-seated resentment against the cards life has dealt him.

He hopes that his lack of a nose will help others become comfortable about the fact that this could one day be their reality too.

“It can affect anyone of them. If they’ve never seen a person who has no nose, when it happens to them, they won’t be able to take it,” he shares.

On the other hand, there are always others who kick him while he’s down, although this tends to be the result of mischief rather than malice.

He claims, “That day, some people threw my clothing downstairs. They also took a packet of rice and cold water and threw at my face when I was resting outside my home. I couldn’t find out who did it, but I know it was the two sons from that family who just moved in. They’re young boys, just slightly over 10 years old.”

Including that family, who lives one unit away from him, three other neighbouring families claim they don’t interact with him. And I believe them.

Every time he greets his neighbours, he is met with stony silence.

“Even though people don’t say ‘hi’ back to me, I will continue saying ‘hi’ to them. Likewise just because a person doesn’t want to give me money, doesn’t mean I won’t thank them too. Sometimes a smile is enough,” he says.

Later on, he reveals why he doesn’t get angry with people anymore through one of his many platitudes: “He who angers you, conquers you. He who irritates you, wins you.”

He might be a familiar presence in Geylang Serai, but to the average Singaporean, Mr Zeng’s infamy precedes him. Those who are aware of his existence know that he has a knack for courting controversy in the news.

For instance, the “Parrot Man” moniker came about after he blamed his parrot for getting him into trouble when he used abusive language on police officers.

He is also a perennial candidate in Singapore elections. In 1991, he had his first brush with politics as a member of the Workers’ Party, where he stayed a year.

Later, during the General Election (GE) of 2006, he ran for the Mountbatten Single Member Constituency. Again in GE 2015, he announced his contest for the Potong Pasir Single Member Constituency, only to change his mind later on. According to reports, he could not afford the election deposit.

Online, he has barely any supporters. From SammyBoy to HardwareZone, criticisms lobbed against him paint him as a troublemaker who’s short of a few marbles.

And it’s easy to see why.

This August, he was embroiled in a tussle with Ngee Ann City’s management after he was asked to move from the underground pedestrian walkway linking Ngee Ann City to Wisma Atria. Not only did he apparently pretend to be a cripple, he also blocked the flow of human traffic.

Just last month, he inadvertently made the news again when it was discovered that the jumbo flat at Geylang Bahru that caught fire belonged to him.

He had formerly claimed to be homeless.

Along the walkway outside his unit, his motorised bike is chained to the railings. Beside it, a makeshift bed lies under a huge umbrella. He shares that this was where he was resting when his neighbour’s sons bullied him. This is also where he sleeps most nights.

There is another swivel chair next to this contraption, which holds a pile of random belongings, such as folded clothes and a ukelele.

Because his unit is located just beside the lift, he has turned a corner of the lift landing into his very own outdoor wardrobe. Hung on the clothes lines are jackets, shirts, patterned scarves, and even underwear.

“The fire happened during the Seventh Month, when people were burning joss sticks,” he begins, implying that the burnings from the Seventh Month caused the fire.

“It started near my sewing machine switch and was still quite small when the police came.”

He claims, “But when they opened the door of my house, the strong wind made the fire bigger. The fire blew onto my fridge, where I put things like oil. It took an hour for the firemen to cut open the lock around the fire hydrant. By then, the fire had already burnt through my home.”

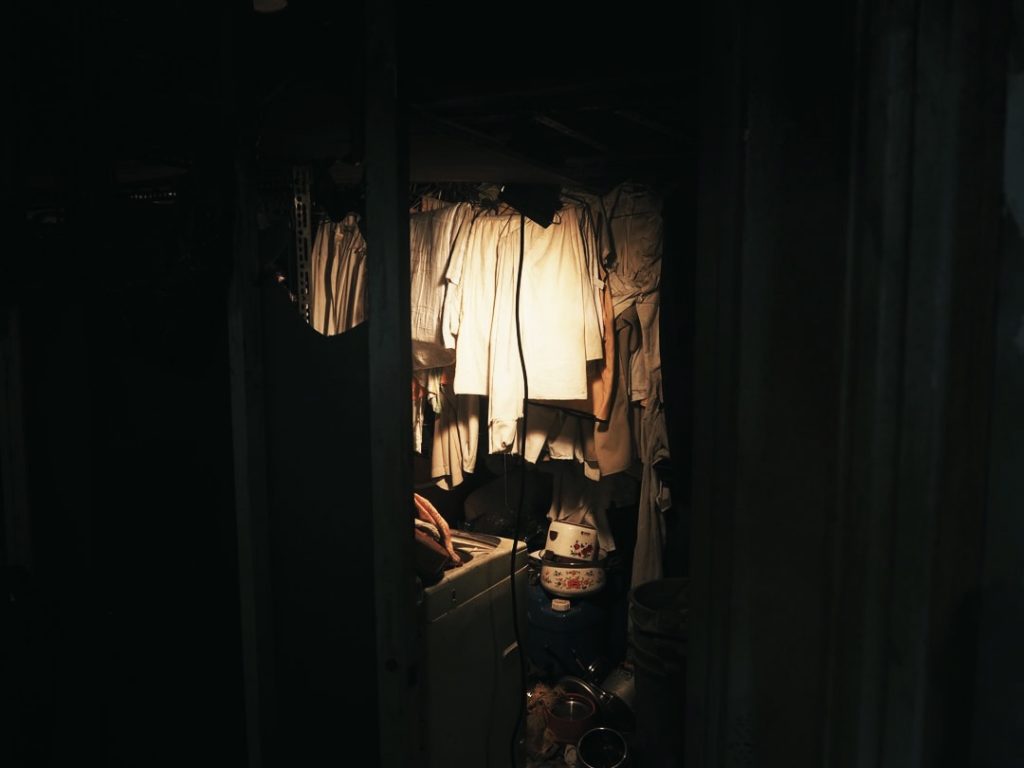

Inside his home, almost everything is broken or burnt and strewn in heaps of rubble. There are old photographs, an empty liquor bottle, and even a few standing fans that have been switched on to ventilate the room. With barely any space to walk, I have to keep myself from tripping over tangled wires.

The charred property is a heartbreaking sight, made worse by the fact that he hasn’t seemed to have made any progress in terms of cleaning up.

“The SCDF told me that if I needed anything, they will try to help. But what can they do? Come on lah, if they want to help, they can suggest something. I’m not going to be a beggar and start demanding things,” he says.

And what about his family? Surely his two grown-up sons should assist.

Again, he stresses how paramount his sense of independence is.

He replies, “No lah, this is not their job! Even the cleaner cannot do this job. Because electrical wire and all this is not safe. Even the glass will cut your hand.”

Nonetheless, a few minutes into our third meeting, he asks me to help hold steady the huge green bin that the estate’s cleaners have placed in his home, while he hoists a destroyed washing machine followed by a sewing machine into it.

In contrast to the photos of him online that often depict him in a wheelchair, his strength is a far cry from the fragility we associate with being physically disabled.

But without the domestic helpers he used to live with in his previous bungalow, it might be months before he even cleans up a fraction of the debris.

Every morning, he picks her up on his motorised bike to take her back to their burnt flat, where she then spends the rest of the day cleaning or running errands.

Her wariness around me is only natural. After all, her husband has never gotten favourable media coverage. When I merely suggest that she must be a loving wife to visit her husband daily, the meek looking woman confidently stares me in the eye.

“Whatever you want to know, talk to my husband. Ask him. Okay?”

But it’s his surprisingly enlightened take on love that gives me insight into their devotion to each other.

“Love is the ability to stay and understand each other until the end of your life. In between, something will test you. Sometimes, you fall and pick yourself up, that’s okay. But if you don’t pick yourself up, you want to hold on to this and that, you die,” he says.

“Whatever good you pick up, you keep. Bad, you drop like hot potato or it will burn your hand. Wisdom is the ability to see the difference.”

For example, he claims that an ex-girlfriend cheated on him and became pregnant with another man’s child. In another twisted tale from his youth, he shares that his grandfather once implied Mr Zeng was “having sex” with his grandmother, simply because he cared a lot for her when she was in the hospital.

And after his father passed away, he cut ties with his siblings who contested his father’s will. Nowadays, apart from his wife’s company, he only sees his sons occasionally, such as on his birthday.

That said, he appears resigned to how his life has turned out. With few to call family, this is perhaps why he treats everyone “like [his] children”.

Even though he means well, it is a quality that’s more irritating than welcoming. By our second meeting, he has already chided me for my double helix piercings, asked why I’m not married at 27, and said that the kueh I buy for him has no nutritional value.

He might just get a heart attack if I tell him I once dyed my hair.

He insists on ‘working’ (i.e., selling tissue paper at Geylang Serai or Ngee Ann City) so as not to be “a financial burden to [his] wife or anybody”, and that he’s unperturbed by his public fall from grace.

Yet I also sense a deep shame attached to what he has resorted to doing.

“Whenever I go to Ngee Ann City, I tell my wife not to come with me. I don’t like her to see what I’m doing. This kind of thing, sitting down there and letting people give you money, I look like a beggar,” he confides.

Despite his relatively public life, he considers himself a “private person” and doesn’t want his family involved in his personal matters. And if he happens to get into a fight, which seems like a regular occurrence, he would tell them to “get out of the scene”. He doesn’t want the authorities to “make use of [his loved ones] to be witnesses against him”.

Not once over the few weeks of us getting to know each other does he express more conviction than when he proclaims, “Anything happen, I die alone.”

In 1996, he went to jail and received several strokes of the cane for molesting one of his patients while placing an acupuncture patch on her shoulder. According to him, the case was “a setup” and that the judge was “biased” against him.

“In jail, people try to be funny with me, so I just wait until they are asleep. Then I whack them. They dare not touch me anymore,” he says. “I do not think prison changed me. Because I done nothing wrong.”

And yet his life is a continuous cycle of things going horribly wrong. It’s no wonder that his unpleasant public reputation doesn’t bother him in the least.

Every single time he hits rock bottom, he has survived.

One day as we’re wrapping up, he asks, “Can I ask you a personal question? Do you think I got a smell coming from me?

“Because inside my body deteriorate already. This is why I don’t want to sleep with my wife. She won’t say that she minds, but it’s just me lah.”

The unexpected question offers a rare moment of clarity, and I finally see who he really is. If he doesn’t sleep with his wife, he never has to find out if she really thinks he stinks.

So no matter his notoriety or the absurd things he says, his eccentricities are reduced to a mere cliché in the end.

Mr Zeng is ultimately just another person who mistakenly assumes they can control how others perceive them.