Benjamin Lee works in a cheese factory, but has always wanted to be a police officer.

The 30-year-old informs me that policemen need to “do paperwork, walk around the neighbourhood, hunt people, and wave at cars to stop”. These are also the reasons he wants to be a police officer.

He proudly displays his passion for the force through his black jacket that’s emblazoned with the word “POLICE” above his left chest and a pseudo staff badge hanging from his belt that reads, in child-like handwriting, “ASPINSPCTOR BENJAMIN”.

I ask, “Do you think you can still be a police officer?”

“I still think I can be a police officer,” he echoes. “But I need to do more work. Running. Exercise.”

Holding a job that has little to do with your childhood ambition may be unfortunate, but it’s not particularly uncommon. Many of us end up embarking on careers that are completely divorced from the astronaut, president, or supermodel aspirations we might have harboured as a child.

But what if you knew Benjamin had Down Syndrome?

Would your impression of his situation change? Would you, because of how you perceive the Down Syndrome community, believe that Benjamin has it pretty damn good after all? And would you, in fact, hope that he is thankful for his job because not many people are as fortunate as he is?

So I settled on the Singaporean dream.

In the pursuit of my own Singaporean dream, I’ve realised that even personal happiness is often shaped by society’s arbitrary standards of success. Which is probably why many Singaporean millennials, including myself (once upon a time), want to start a family, buy a house, and excel in career.

But for people who exist on society’s fringes—if they are disabled, low income, or not academically inclined—do their dreams have a place in Singapore? Do we have inclusive mechanisms and policies to help these people realise their aspirations? Or do they eventually, after multiple probable setbacks, learn that the trite ideal of starting a family, buying a house, and excelling in their career are in fact dreams of the privileged?

Before arriving at the Down Syndrome Association, I hoped to find answers to these questions.

Today, she works in the housekeeping department at Rasa Sentosa. With a three-day work schedule, it’s a job that keeps her happy because her bosses treat her well. She also “feels like a big part of Rasa family”, in addition to the friends she has at the Down Syndrome Association.

In contrast, Wan Yi used to be bullied during primary school, where her classmates would “call [her] vulgar words” and “make fun” of her. This made her feel “guilty” because she found it hard to make friends.

Noticing my difficulty catching what he’s trying to say, Wan Yi and Benjamin jump in by helping me make out his speech. I learn that he’s always wanted to be a chef, although I’m unable to make out why and how he came to develop this interest in cooking.

Frankly, attempting—and failing—to speak to Ryan leaves me with the sobering realisation that many of us give up interacting with and trying to understand the Down Syndrome community because we simply don’t know how to talk to them. Undeniably, it’s more convenient to nod and smile than stubbornly find ways to rephrase our questions so we can have proper, successful conversations.

It’s unsurprising then that I come away from our interviews with even more questions than I had at the start.

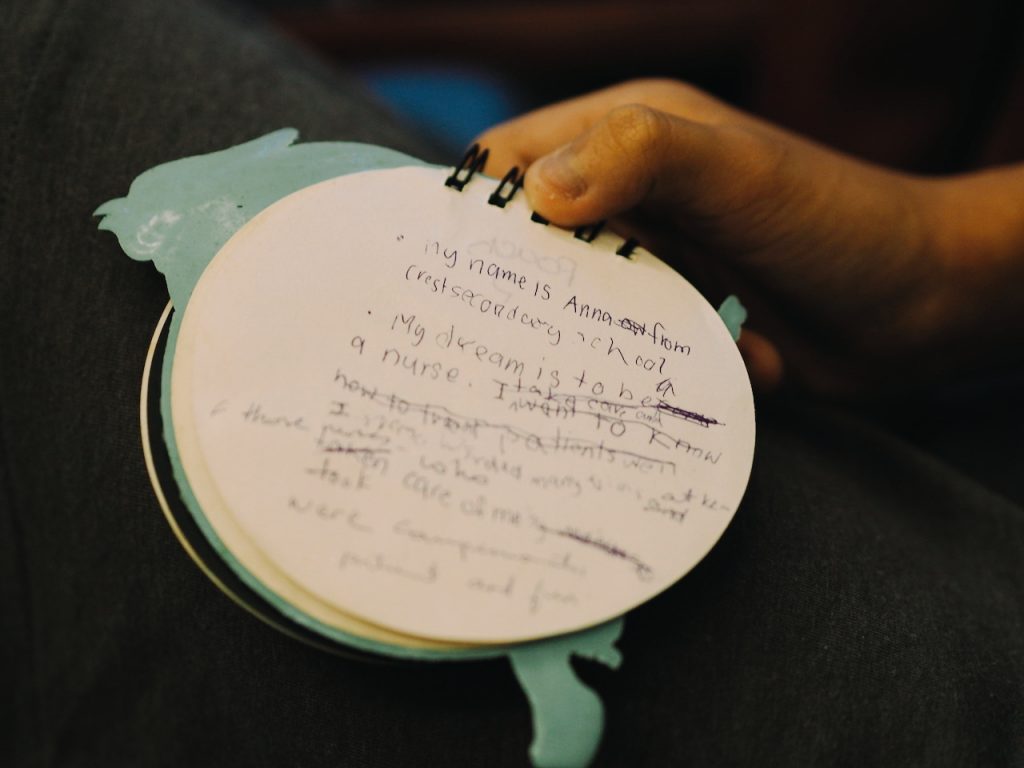

If you’re in your formative years or a teenager, like Anna Ow, this support system can be crucial.

The secondary two Normal (Technical) student at Crest Secondary School tells me she wants to be a nurse when she grows up. She says this with more determination than I’ve seen in many other 14-year-olds, or adults, for that matter.

During a fashion show held at Rainbow Centre, a special education institution that Anna used to attend, she once dressed up as a nurse. And at home, her father would pretend to be sick so Anna could use her doctor’s kit to ‘care’ for him.

Anna’s mother, who accompanies Anna for the interview, shares that her daughter underwent open heart surgery at the age of one—the first in a string of hospital visits over the course of her childhood. In the hospitals, Anna would interact with doctors and nurses because she found them interesting.

“She’s not afraid of needles. When the doctors told her to close her eyes, she wanted to keep them open to see what was going on,” her mother shares.

I also learn that she has tuition thrice a week, considers math exams the most stressful part of school, and calls recess as her favourite subject. Turns out, we have more in common than I thought.

Despite her disjointed answers, I have no problem understanding what she’s saying: her dreams, interests, and passions are no less different than those held by children without Down Syndrome. But society is rarely as optimistic or open-minded.

Her mother adds, “I feel for her because her dream might not come true, especially because medical school isn’t so much about passion. It’s also about academics.”

She is also aware that a mainstream school, which Anna attends now, presents an entirely different minefield when it comes to how people perceive her daughter. Then, as though to reassure both me and herself, she explains that it shouldn’t be an issue because Anna is “mature in her thinking”.

Long after our conversation ends, I continue to wonder about the possibility of Anna becoming a nurse and the practicality of the policies that would empower her to do so. I don’t want her interest in helping people to stop at science comics, but neither do I want her to only receive help under ‘social welfare’ because of her condition. The latter is perhaps the bigger issue that we need to confront as a society when it comes to actualising the dreams of the Down Syndrome and other special needs communities.

Mostly, I am disheartened by all the possibilities in which we encourage our children to dream big and the limiting ways in which reality eventually forces them to ‘wake up’.

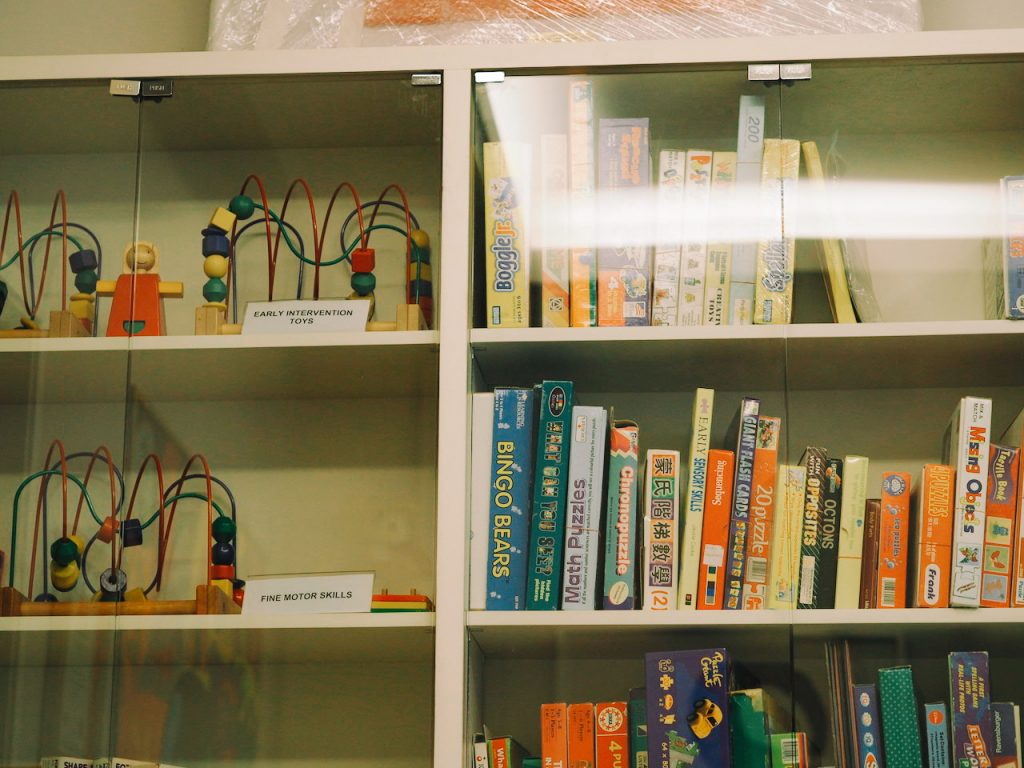

To build public awareness and education, some of the measures the Down Syndrome Association puts in place include helping families of those with Down Syndrome learn how to care for their family member, and providing the skills, knowledge, and self-independence for those with Down Syndrome to build their confidence.

The association carries out talks with various sectors of the community, from toddlers in kindergarten to elderly from the Chinese Development Assistance Council, hoping to abolish old wives’ tales and misconceptions about the Down Syndrome community.

Andrew Soh, the assistant director at the association, explains that it helps to have corporate partners who are willing to engage with the community. For instance, their work is similar to organisations like Make-a-Wish, ensuring the dreams of the Down Syndrome community materialise.

Nonetheless, the lack of awareness about the community’s needs means there’s still quite a way to go. Andrew has to often remind companies not to just take the members of the Down Syndrome Association to visit tourist spots in Singapore. Instead, inviting them to their workplaces would be more meaningful in exposing the world of work to them.

But he is optimistic about turning this “disadvantage” into an advantage. For example, if someone with Down Syndrome is easily recognised, their faces can “deliver the message” or spread awareness about the mental disability.

“We’ve been around for about 22 years, yet there is still so much talk of normalisation. Society is still coming to grips with the term ‘special needs’. We seem to either hold the community on a pedestal or totally ignore them,” he says.

I am frustrated by this statement because he’s right. When I was assigned this story, I was afraid I would end up either romanticising or trivialising the dreams of those with Down Syndrome, in a bid to normalise discussion about a community I’m admittedly unfamiliar with.

But the Singaporean dream has been the great equaliser in this case. Speaking to Benjamin, Wan Yi, Ryan, Anna, and even Andrew himself, makes me understand how lucky I am to be able to reject the conventional, banal, and lame Singaporean dream of starting a family, buying a house, and excelling in career. Now, I find myself less averse to these notions, and instead more grateful that I get to even have them at all.

As I reread my interview notes several times over, I’m aware that my reactions to their responses have been filtered through the seemingly standard privilege of being able-bodied, intellectually capable, and better than average looking.

Still, there is one final dream I haven’t discovered.

Before I can ask Andrew what’s his dream for the community, he shares: “I would like to see the Down Syndrome community get to perform at the National Day Parade.”

It’s a poignant ending note, precisely because this simple dream is a lofty one for the Down Syndrome community. Yet, as I pen this final paragraph, I find myself overcome with sheer hope that someone from this year’s NDP committee would read this and decide to fulfil this one Singaporean dream.

Have something to say about this story? Write in: community@ricemedia.co.