The first one I encountered was Ang Mo Kio Ave 4’s so-called ‘4-D Tree’, which appeared suddenly in the mid-2000s, in the field behind my old house.

Overnight and seemingly without cause, devotees began flocking to the tree in droves. They burned joss sticks, offered packets of food, and covered its low-hanging branches with colourful scraps of cloth. Chairs mushroomed from the grass so that the old uncles—always a core tree shrine demographic—could sit and wait; until one fine day, when LTA arrived and decided that YES, this is the perfect spot for a new MRT station.

However, the mystery—and my curiosity—remained. I never figured out why so many people were suddenly convinced of the tree’s sacred nature. What was the connection to 4-D? Or for that matter, why do people worship these seemingly ordinary trees at all?

Unlike most other makeshift shrines which acquire their divinity rather haphazardly, Toa Payoh’s God Tree Shrine is a registered place-of-worship with its own security, ‘trustees’, and charitable services. Nestled within the perpetual bustle of Toa Payoh town centre, it is situated on a spacious pavilion and kept scrupulously tidy by Manager Mr. Pan (no relation to the author) and caretaker Mdm. Yeo, whose mother also cared for the shrine until her passing a few years ago.

The entire operation is overseen by the Toa Payoh Merchants Association, who took over its ‘operations’ in 2013, when the God Tree collapsed and its previous CEO ‘fled’. They perform most of the duties, which range from collecting donations to pest control.

Given its fame, popularity and relatively well-documented history, I thought it would be a good launchpad to learn more about tree shrines in Singapore.

This logic—as I soon learned—would turn out to be total bullshit. In fact, the opposite is true. The shrine is so well-established and so built-up that few devotees even register the presence of a sprawling Banyan.

One Malaysian woman who visits the shrine every day told me that she prays at the God Tree Shrine because it is more accurate (‘zhun’) than others. Most devotees, however, know nothing about the tree except that it ‘has been there for a long long time’.

“Catch him when he comes around in the afternoon,” everyone said.

However, Mr. Pan proved no more knowledgeable than the rest when I finally tracked him down on a Saturday afternoon. After shaking my hand, he shrugs and tells me that ‘nobody knows how this tree came to be worshipped’. ‘The Book’—which had by then acquired the status of a Dead Sea Scroll in my mind—turns out to be an NHB-produced leaflet with half a page on ‘Tree Shrine of Blk 177’.

It retells the familiar Bulldozer story of 1965, when the tree defied PAP economic policy by halting several bulldozers in their tracks. Monks sent in to appease the tree proved helpless and the developers eventually gave up and built around the tree.

After the plans fell through, a small statue of Guan Yin was placed in the Banyan’s hollow, and Ci Ern Ge—the God Tree Shrine’s original name—was born.

This, of course, raises more questions than it answers. One solitary god tree could be dismissed as a superstition, but six god trees indicate a wider system of belief.

Hold tight for some history.

Many of the ‘Chinese’ tree shrines in Singapore are dedicated to a deity in the Taoist pantheon called Na Tuk Gong. The Toa Payoh shrine has an altar for Na Tuk Gong, as do other shrines like the makeshift one found in Joo Chiat’s Tembeling Road (in a carpark, under a Banyan tree).

The strange thing is, Na Tuk Gong cannot be found in China, Taiwan or any of the East Asian countries with strong Taoist traditions. This is because Na Tuk Gong is actually a mispronunciation of ‘Datuk’, and the Chinese who worship Na Tuk Gong/Datuk started out by worshipping the Malay/Muslim Keramats of South-East Asia.

Although many of the Keramats like the Keramat Siti Maryam (Kallang) have been demolished to make way for ‘progress’, most are still around today. Notable examples include Keramat Kusu (Kusu Island), Keramat Sharifah Rogayah (Duxton Park), and Keramat Iskandar Shah (Fort Canning/Bukit Larangan).

So why did Chinese people worship the Keramat?

According to Mr Ong Kian Sin, a Taoist priest, the answer is relatively simple. Chinese people, he jokes, have a habit of worshipping all and sundry.

Taoist tradition reveres ‘Tu Di Gong’ or guardian deities who hold sway in a specific geographical locale. In South-East Asia, these deities would naturally be Malay rather than Chinese. Hence, the first Chinese migrants to South-East Asia began praying and making offerings to Keramats, which they understood to be the local ‘guardian deities’.

Over time, the honorific ‘Datuk’—which was used to address the Keramats—became ‘Na Tuk’, and the practice was absorbed into mainstream Taoism in the same way that Guanyin was absorbed from Buddhism.

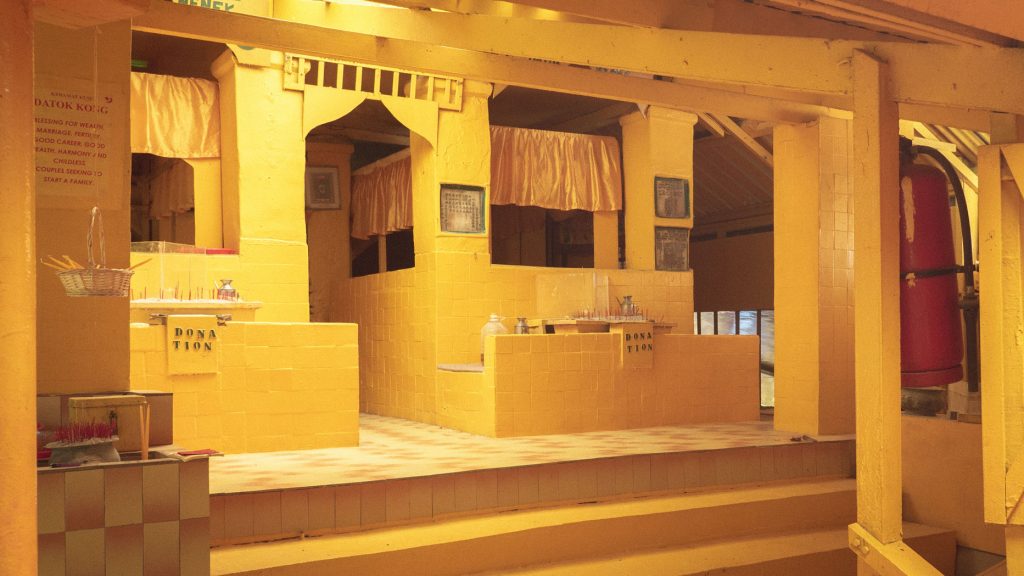

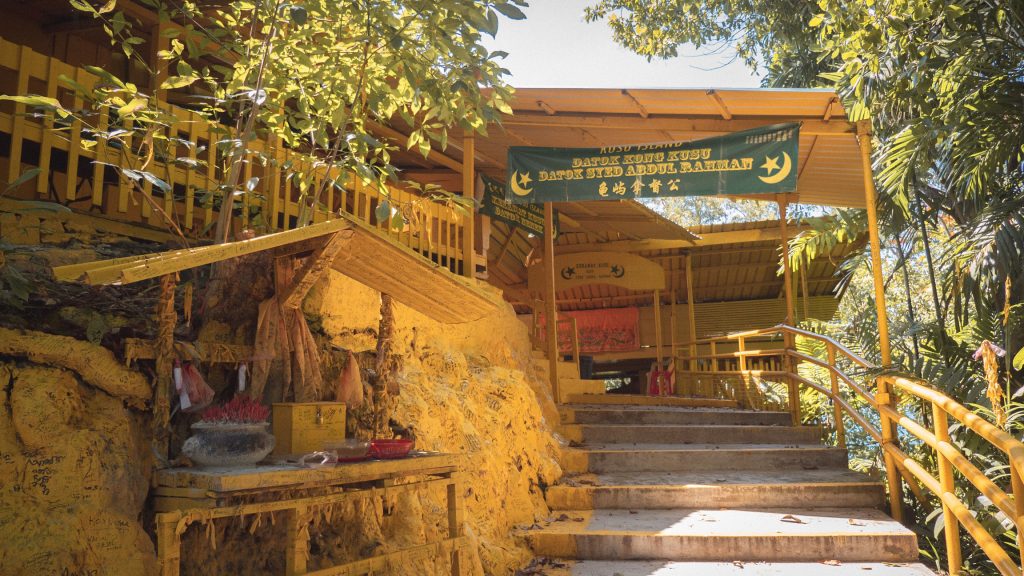

On arrival, make your way up the hill and you will chance upon a unique sight: a bright yellow building which houses both a Datuk Kong temple and three Malay Keramats.

These Keramats were originally built in 1816 to honour a pious family: Syed Abdul Rahman, his mother Nenek Ghalib, and his sister Puteri Fatimah. Over time, however, the keramat tradition blended with Taoist beliefs, and ‘Datuk Kong’ was added to Keramat Kusu’s signage for the benefit of Chinese pilgrims.

In November every year, during the Kusu Pilgrimage, they climb the 152 steps up to Keramat Kusu so that both Nenek and Na Tuk Gong are rightly honoured—with incense, food, and prayer.

The answer is nothing and everything. Although the keramat is *supposed* to be a grave in the Sufi (Islamic Mysticism) tradition, there is strong evidence to suggest they started life otherwise. Just as Na Tuk Gong shrines evolved from Keramats, research suggests that the Keramat is itself the offspring of older ‘tree shrines’ which were worshipped long before the arrival of Islam in South-East Asia.

According to Muhammad Faisal Husni, who wrote his masters thesis on the history of keramats, there is a strong connection between the Keramats and their immediate environment. In his dissertation ‘The Grave That Became a Shrine’, he notes that many of the Keramats in Singapore are situated in unusual locations. They are often sited on top of a small hill, next to water, or, more often than not, under the shade of towering Banyans.

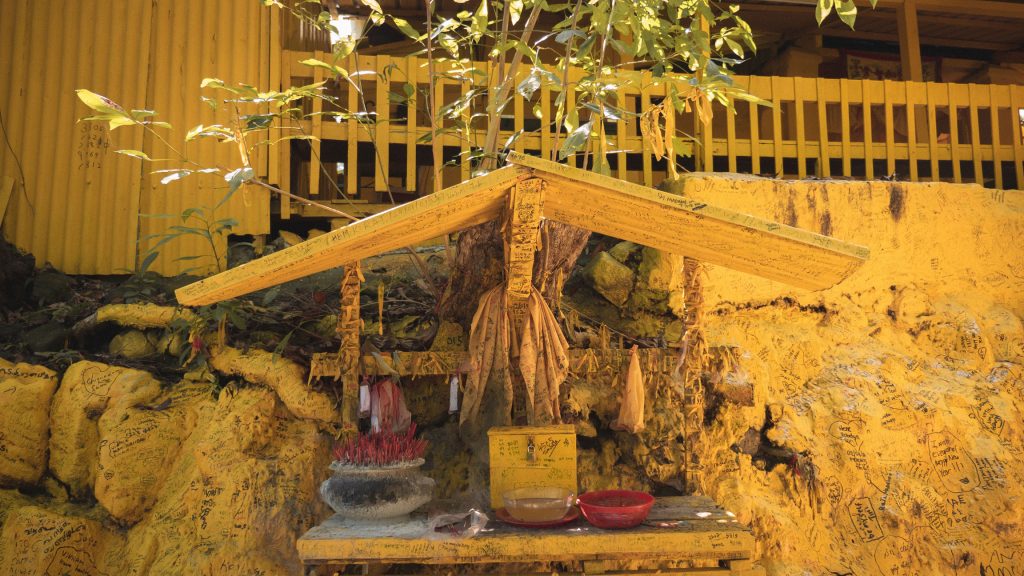

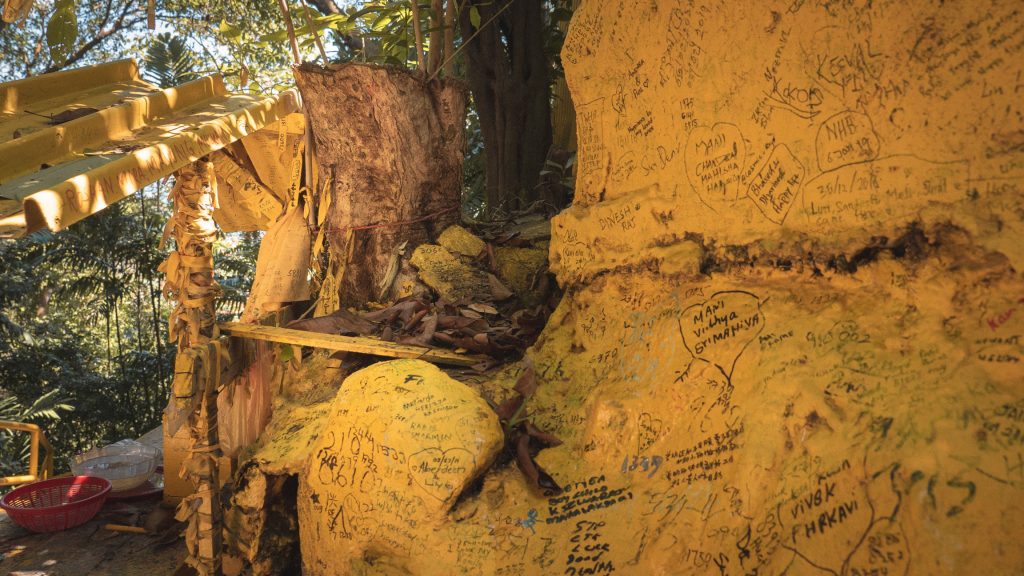

Examples abound. Keramat Kusu is located in a thicket so dense you cannot glimpse the sea even though it is barely 50m away. Next to the three Keramats and the Datuk Kong shrine is a towering Banyan draped with pieces of cloth. After burning incense and offering packets of Pulut Kuning (saffron rice) to the Datuk, Kusu pilgrims write their wishes/prayers on bolts of cloth to be tied to the tree’s branches.

Likewise for Keramat Bukit Kasita and the now-destroyed Keramat Siti Maryam. The former is surrounded by massive Banyans just like its Kusu cousin, and the latter boasts an even stronger connection to nature. The tree that once watched over Keramat Siti Maryam is described as ‘central’ to the shrine complex, and Wak Aiyim—the shrine’s longtime custodian—was vocal about its importance.

Mr. Husni writes that trees are not just ‘living altars’ for devotees to worship, but an element as integral to Keramat’s holiness as the bodies interred beneath. After all, Malay tradition holds trees in high regard. Some trees are said to be the home of spirits, and all trees possess ‘Semangat’ (Soul substance) under the framework of earlier, pre-Islamic beliefs.

Hence, Faisal suggests that these spaces are clearly sacred, and the graves might have served to ‘legitimise the earlier worship of these spaces but in a different form’.

In other words, the ‘Muslim saint’ narrative might have been added to lend a veneer of Islamic propriety to a space that was already sacred to begin with. Or as Dr. P.J Rivers describes in an earlier essay entitled ‘Keramat in Singapore in the mid-twentieth century’: “Belief in sacred hills, trees or stones grew about such objects and then refocused on a convenient burial site identified with apocryphal saints.”

Given their power and reach, it’s hard to believe they did not leave a mark upon the cultural landscape.

Unlike other religions in Singapore, Hinduism has a direct connection to trees and tree shrines. MUIS has an uneasy relationship with the keramats because such saints are contentious in ‘mainstream’ Islam. If you ask a Taoist or Buddhist Priest, they will likely tell you—as Mr Ong told me—that tree shrines are part of Singapore’s ‘folk beliefs’. They are tolerated but they do not have a place in the official theology.

In Hinduism, however, trees are revered and worshipped without controversy. As Dr. Vasudeva Battachar—Chief Priest of Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple—explains, Hinduism worships the Supreme Power, which can take on different forms like trees, animals, or even elements like fire. This power is worshipped in different forms to get different things, he tells me.

Sensing my confusion, he uses the metaphor of electricity; a power which we experience in many different forms—like cool air from the air-conditioner, light from a bulb, or sound from a karaoke microphone.

Trees are an aspect of this supreme power, which can manifest in different forms.

“God is living in everything. This is our philosophy. You do not need to go to any particular place to see the gods. If you feel that god is here, then god is here. If you are praying to the tree, then god is in the tree,” he explains.

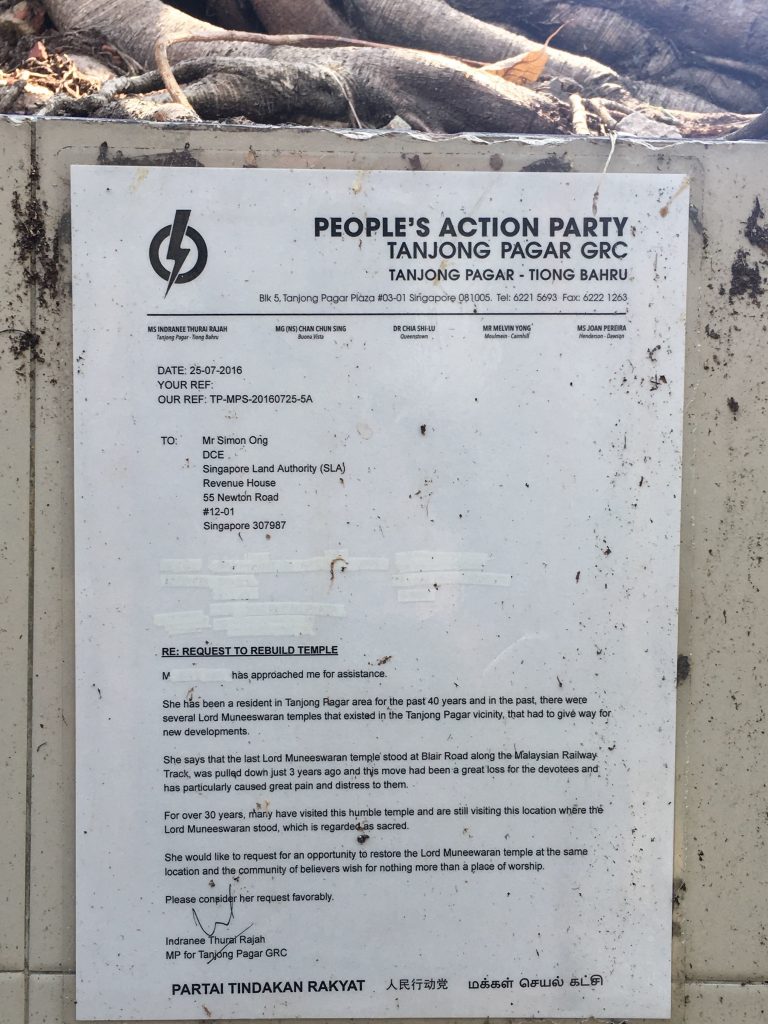

Inside, you will find a large Banyan growing from a concrete pedestal, with pictures of cobras nailed to the trunk and an MP’s letter pasted below. According to the letter, there was once here a ‘temple’ to Lord Muneeswaran. It had been around for at least 30 years, until it was ‘pulled down’ to make way for development.

A petitioner, a longtime resident of Tanjong Pagar, later sought help from MP Indranee Rajah because the temple’s destruction had caused ‘great pain and distress’ to the community of devotees. She then requested an opportunity to restore this sacred temple at the same location—a request which appears to have been granted, judging by how the tree is cordoned off by metal fences.

Mr. Marwan, a devotee I encountered, informs me that they are ‘abodes’ for Kali-ma and Muniyadi, an earth deity. It is his second visit to this particular shrine, but he has been meaning to visit for the longest time.

When I show Chief Priest Vasudeva a photograph of the shrines, he doesn’t even raise an eyebrow. Such shrines, he explains, exist for the convenience of devotees, and praying to them is no different from praying at a temple or at home. The only difference, he claims, is the higher concentration of power in temples—a result of the many mantras which are chanted in the main sanctum day and night.

Barring the invention of a time machine, we will never know for sure. However, most Keramat scholars believe in some degree of religious intermingling. In Singapore and Malaysia, Hindu devotees often visit Na Tuk Kong shrines and Keramats. In Ampang, for instance, there is a ‘Hindu Datuk’ named Mimisan whose shrine is described in Tamil. Closer to home, the Joo Chiat Na Tuk Gong shrine is apparently very popular with Hindu devotees. The local residents I spoke to invariably described the Na Tuk Gong shrine as ‘a tree popular with Indians’.

Likewise, non-Hindu visitors to Keramats often adopt practices found mainly in Hinduism, like offering flower garlands and ritually consuming the ‘leftover’ food on the altar.

As Muhammad Faisal Husni notes in his dissertation, this is not dissimilar to the Hindu practice of Prasad, where food is first offered to the gods before they are consumed, in an act meant to symbolise a devotee’s humility before a ‘higher’ power.

Hence, he concludes, “It is possible that vestiges of pre-Islamic Indian and Hindu culture still remain—whether still recognisable or not—in the practices of Muslims in Singapore, especially the Indian Muslim community.”

Today, the bananas are gone, and there is not a single devotee in sight. One of the shopkeepers nearby who knew of its existence only laughed when I asked about it.

“Aiya, you know what Singaporeans are like!” he exclaimed.

The sentiment is understandable but misguided. There’s more to Singapore’s tree shrines than just superstition or a desire to strike 4-D.

Just as a tree’s rings can help to decipher a region’s natural history, tree shrines tell us about the history of Singapore itself. They are a living chronicle; of Hinduism’s intermixing with older animist beliefs, of Islam’s arrival in SEA, of the Chinese migrants who came ashore, adopted these beliefs, and blended them with traditions of home.

And of our latter-day god: 4-D.

Sadly, however, many of Singapore’s tree shrines are disappearing. Keramat Siti Maryam and Keramat Syed Yasin have been exhumed and moved. Likewise, other shrines in North Bridge Road, Lornie Road, and Leonie Hill seem to have vanished without a trace; the only evidence that they once existed are grainy photographs stored in the National Archives.

This—to me—is a terrible shame because there is no better symbol of Singapore’s multiculturalism. Not the rah-rah, cringe-y version that is constantly being shoved down our throats, but an ‘organic’ multiculturalism: born of lived realities and so thoroughly interwoven that you cannot tell where Hinduism ends and Taoism begins. (If anything can be said to have ‘ended’ at all.)

So pause and take a look the next time you come across a humble tree shrine. They might not look like much, but their roots are strong and far-reaching, extending deep into our shared history.