“My stay in IMH was one of the worst periods of my life. Yet it truly was a turning point. Without it, I’m sure I would just be mucking about in life now, or even be dead.”

Four years ago, 26 year-old Miguel was still serving in the army as a clerk.

On one occasion, his hands began to tremble and his vision began to fade. All he could see was grayed tones, almost as if all the colour in the world had been drained away.

Realising that something was amiss, he informed his superior who ordered him to go to IMH straight away.

“When I was in the cab, I was laughing and crying the entire time. I even tried to jump out of the moving vehicle,” he tells me.

Miguel has only a vague idea of what happened when he arrived at IMH, but friends and family who were at the premises have recounted his rabid behaviour.

“They told me that I was drooling and hit my head on the wall multiple times, and I didn’t stop even when I was bleeding. Apparently, I also tried to hit the nurses and security guards.”

After calming down, he spoke with the doctor who told him that because of his suicidal behaviour, he would be warded for observation indefinitely.

He goes on to paint me a picture of what life is truly like behind the walls of IMH.

One would be forgiven for thinking that I’m describing a scene from ‘One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest’.

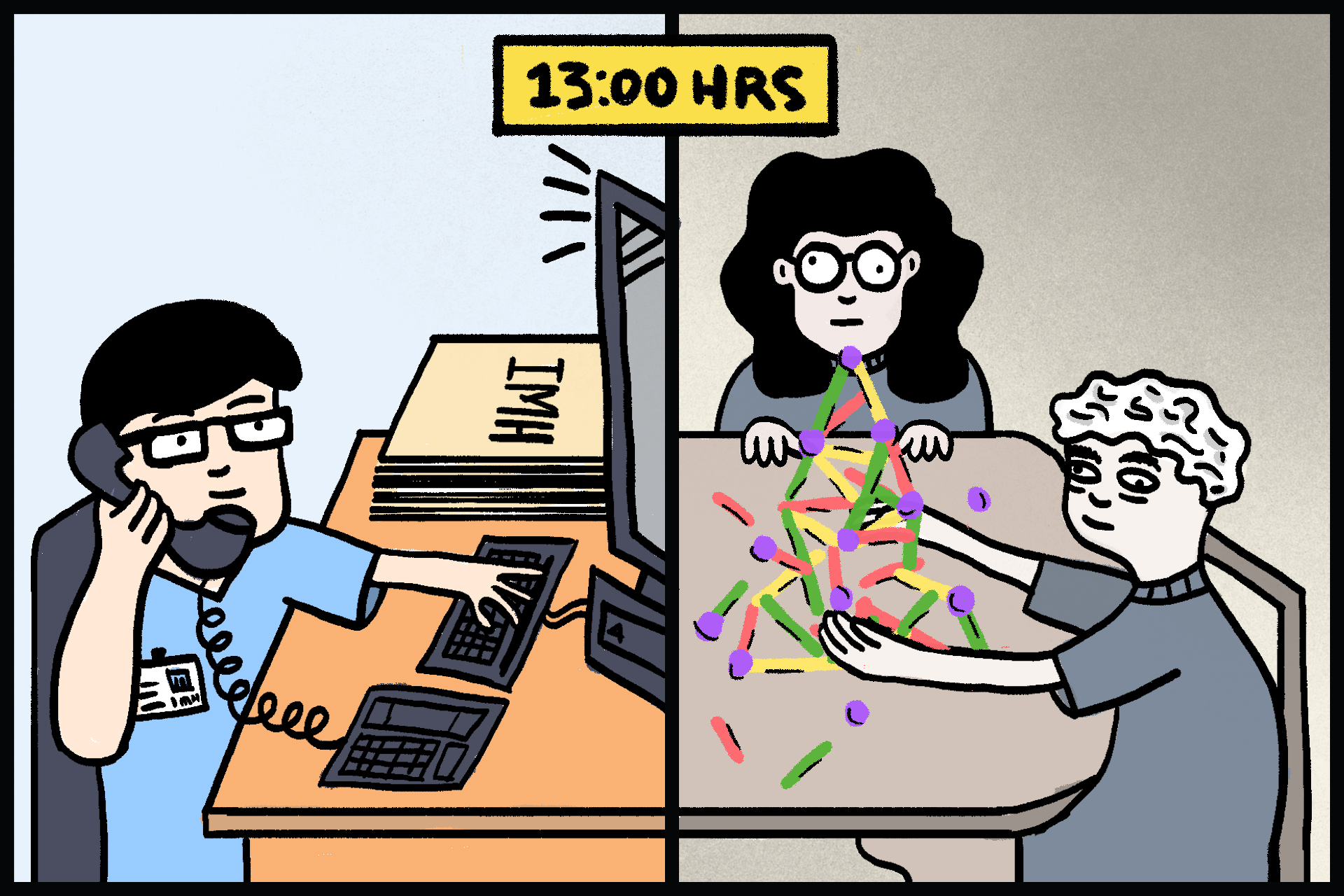

An hour later, case officers and doctors start to make their way around the wards, and this, for Miguel, was the most exciting time of the day.

“I would be praying that they would call me in for a review as I didn’t want to spend any more time in there. I just wanted to be discharged.”

As Miguel comes from an upper-middle class family, he only had to worry about getting himself better so that he could be discharged. Other patients might not be so lucky.

Erron (Not his real name), a Case Officer at IMH said, “We help to assess if patients are fit for discharge not just by their medical status, but whether or not they have any issues such as housing or financial needs.”

As a case officer, his main goal is to help his patients find their feet in the community by aligning them with relevant services such as IMH Job Club (a service which eases the employment process for people with psychiatric conditions).

“We take a holistic approach when categorising our patients by understanding their needs from the Social, Medical, Community and Psychiatric domains.” He adds.

As the common room was locked and patients had nowhere to go, Miguel had little choice but to make the most of it.

He would meet people like Jesus, a man who believed himself to be the incarnation of Christ; Ah Beng, a Chinese gangster who had tattoos all over his body; a man accused of being a pedophile, and a man who was constantly fiddling with his flaccid penis.

In the common room, Miguel and his motley crew of patients had to find ways to entertain themselves for the five hours that was regularly made available to them.

For entertainment, there was a chess set with missing pieces, newspapers, 3 sets of poker cards that were mixed up, drawing blocks, and crayons.

“I had quite a lot of fun playing Tai Di with the shitty cards. I remember there was one game I got six 2s (The strongest card in the game) and beat all of them. Plus, some of them were not in the right frame of mind, so it was really easy to cheat.”

Patients also had restrictions placed on them. They were not allowed to bring mobile phones or electronic devices in with them, nor could they bring in cigarettes. Luckily for Miguel, a smoker, Ah Beng had someone smuggle in cigarettes for him. They would then start their own marketplace by engaging in barter trading. Miguel would exchange packets of chips or donuts he got from his family for cigarettes with Ah Beng.

At this point, one would be forgiven for thinking that I’m describing a scene from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest.

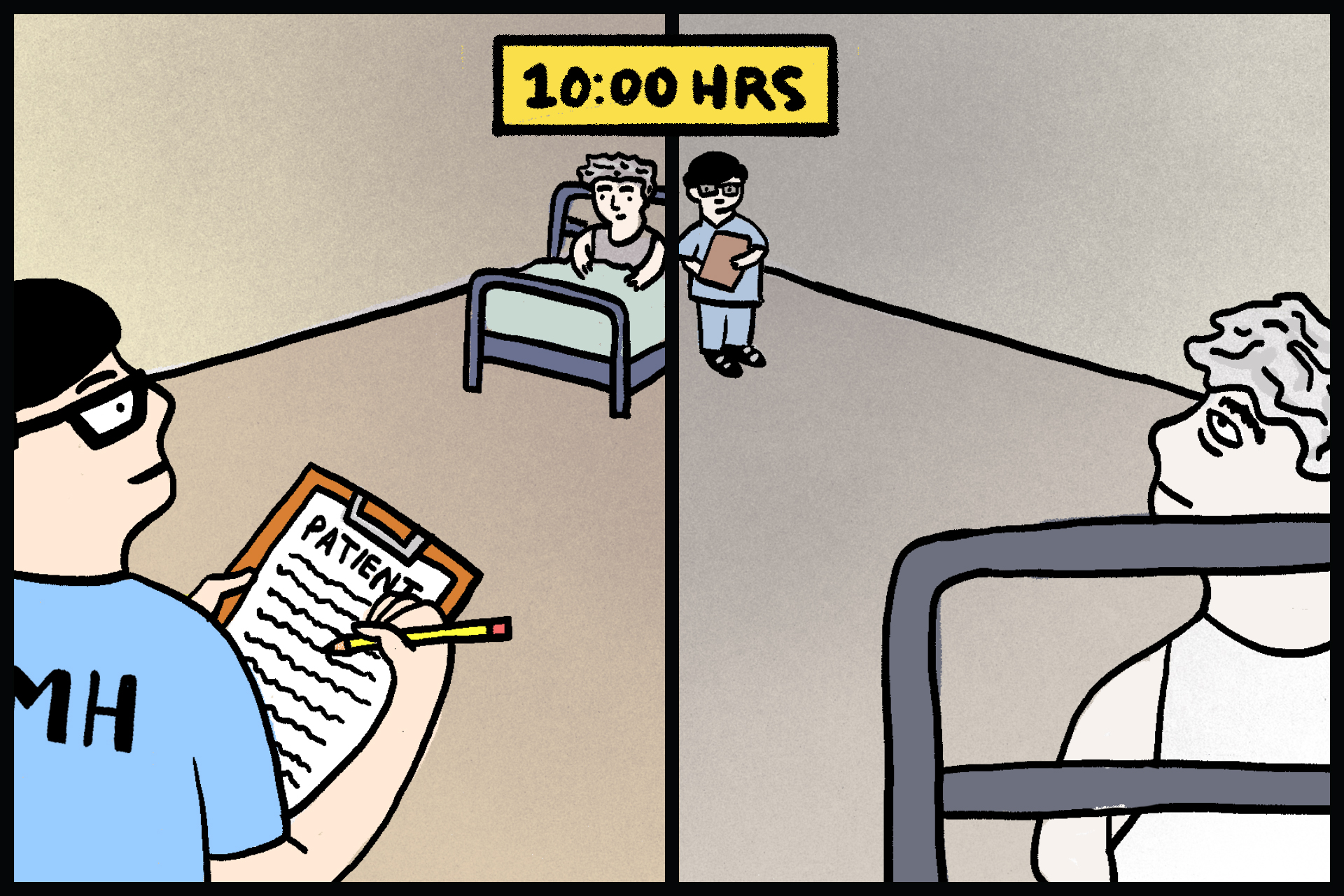

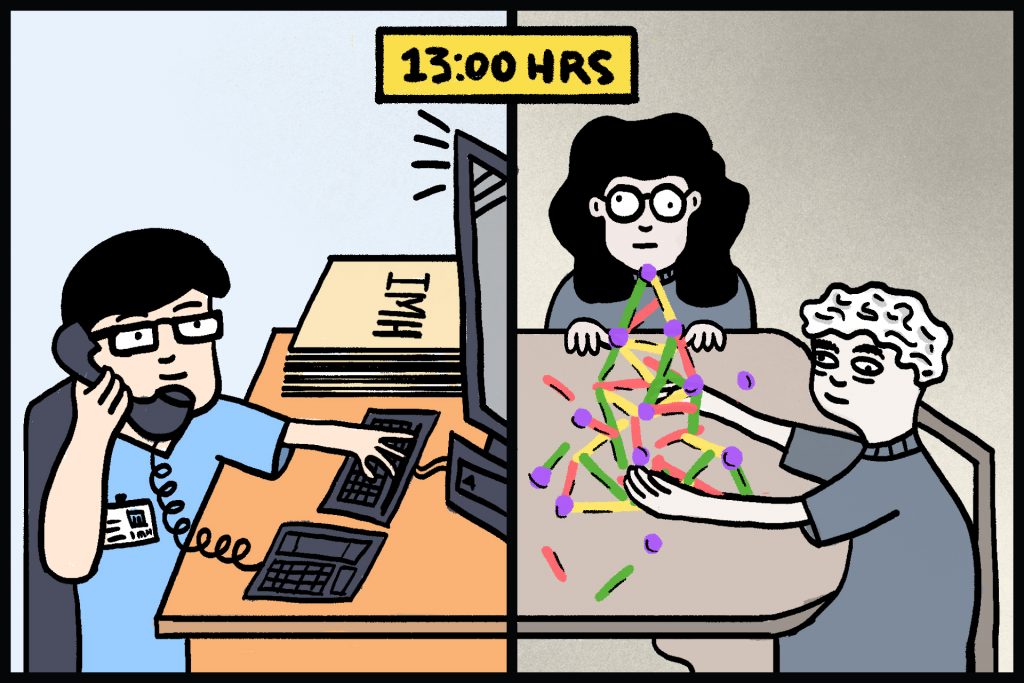

Miguel gives me another example on how a patient’s illness could manifest.

“There was this guy in his forties who would strip naked and pee all over the floor, before lying in it while maintaining a laughing buddha pose.”

He explains that a nurse told him that the patient used to live with his father and was allowed to roam naked at home, but was sent to IMH after the passing of his father.

After spending time in the common room, patients are usually allowed to have visiting time with their family and friends. For Miguel, this was what kept him from plunging into further depression, and was the only time of the day that he really looked forward to.

“Most of the other patients didn’t get visitors so some of them would come by and sit down for a chit chat.”

They would go back to the common room until 10PM when the lights would be switched off so that everyone could sleep.

This, however, didn’t necessarily signal the end to the hysteria.

“One of the patients started scratching his leg with so much force that it started to bleed profusely. It was only after he was restrained by the nurses that he stopped doing so,” Miguel describes, referring to a particular incident.

“Almost every night, I would hear shouting and screaming from the female dormitories, it was quite freaky,” he adds.

There is always a chance that a patient might have a self-fulfilling prophecy, or worse, use their diagnosis to justify their actions.

“I never thought that there was never anything off with me up till National Service.”

Miguel had been brought to see a counsellor at the beginning of his service after he answered “Yes” on a questionnaire that asked if he had had any suicidal thoughts before.

“Back then, whenever I had any rage to deal with, I would just go to the gym to unleash my anger.”

Yet he admits that while this relieved his stress, it wasn’t the most conclusive way to deal with his anger issues.

In fact, It took Miguel more than two years and several sessions of therapy after his IMH episode before he was properly diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder. While the symptoms might’ve been clear for the doctors to diagnose him, he reckons they might have had legitimate reasons to not disclose the information.

“There is always a chance that a patient might have a self-fulfilling prophecy, or worse, use their diagnosis to justify their actions.”

He has also recently graduated from university in, you guessed it, Psychology. He is now waiting to be accepted into his school of choice where he will undertake a Masters Programme. He cites his desire to understand his condition better as well as wanting to help others in his situation.

However, not every patient assimilates back into society as well as Miguel.

Due to the sheer range of mental illnesses and the wide spectrum of symptoms that afflict patients, there might be limitations to what they might be able to do for a living.

Aside from IMH Job Club, patients of IMH can also get vocational training at Bizlink Cafe, a F&B establishment in IMH where they can work in customer service and pick up skills in food preparation.

Having this option will ensure that patients enrolled in the programme have another skillset under their belt as they look to get their lives back on track by getting a job.

Erron shares, “ We hope for patients to achieve a proper semblance of a normal daily routine. It is about helping him or her to get accepted by society and becoming a contributing member to the community and his or her family.”

Miguel is all too familiar with the reality that the problem is deeply rooted in our culture.

“Mediacorp dramas always use terms like ‘You eat wrong medicine ah?’ and ‘You never eat medicine is it?’” he says, referring to scenes where one character chides another for making an error deemed to be brainless or stupid.

“These lines really sicken me, as they undermine mental-illness as a whole. Unfortunately, this is human problem, and it will never fully go away. People will always fear or discriminate others who are different.”

This is why Miguel is all for government intervention, specifically when it comes to educating the public on mental health and disorders.

After all, not everyone who’s warded indefinitely thrives like the old man who paints murals.