Image credits: Unsplash

The year is 2021. And yes, we are still debating the hijab in Parliament.

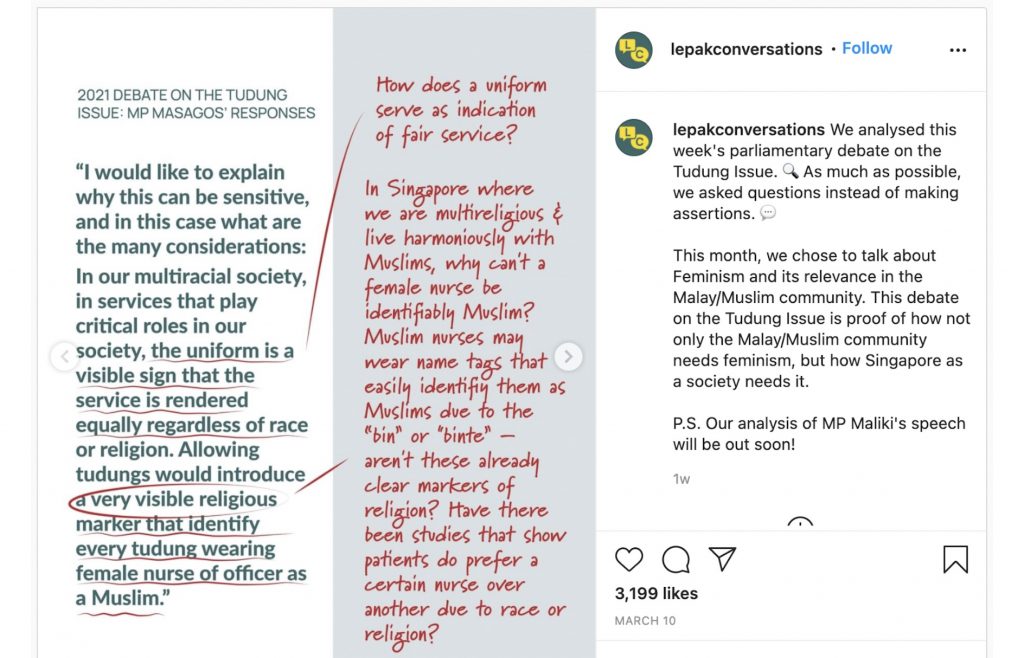

On International Women’s Day, Singaporeans were treated to a statement made in Parliament by Minister for Social and Family Development of Singapore (and Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs) Masagos Zulkifli: allowing the hijab “would introduce a very visible religious marker that identifies every tudung-wearing female nurse or uniformed officer as a Muslim”.

His statement was a response to opposition MP Faisal Manap’s persistence to resolve the issue in Parliament since nearly a decade ago. Clearly, the discourse over this issue has been long and dragged out.

A Brief History of the Hijab Debate

It was in September 2013 when the then Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs Yaacob Ibrahim wrote a note on his Facebook page (remember those?) that employers here have exercised flexibility on the practice—except in certain professions.

He said that police officers and Singapore Armed Forces servicemen are not allowed to wear or display religious symbols on their uniforms or faces—this includes Muslim policewomen wearing the hijab on duty. As if to make an allowance, he added, “But when they are out of uniform, they are free to wear the hijab, as indeed many do going to and from work.”

In response, angry netizens and an online petition surged forth in support of the hijab for nurses and front-line officers. It was taken down before it reached the goal of 20,000 signatures.

Months after this, he reiterated again that wearing a Muslim headscarf at the workplace would be “very problematic” for some professions that require their staff to be in uniform. Since the incident, the issue of the hijab has pervaded the public space—relevant organisations and support groups have spoken out about it as a distinct form of workplace discrimination.

So what gives? Why is the hijab continuously seen as unfit to be part of the uniformed profession? As the debate drags on today, it only exposes more pressing issues. Who should be tabling the discussions? Are Muslim women being represented enough, and what does a ‘secular’ society really mean?

The following year after Yaacob Ibrahim’s statement, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong also weighed in on the debate. While he said he understood the position of why the hijab should be integrated into public service or uniform personnel, the issue is broader than the hijab itself, and is about “what sort of society do we want to build in Singapore”.

By this, he was referring to a “multi-racial society”, where everyone has full and equal opportunities and where “the minority community can live its own way of life, practice its faith to the maximum way possible and not be oppressed, or marginalised, by the majority”.

The tussle continued in Parliament in 2017 when both Faisal and Masagos raised the need to have a public discussion on the hijab. To sum it up, no resolution was made and Masagos seemed to believe in a closed-door approach while Faisal supported an open, public discussion.

It’s curious how two men are politicking over the rights of women to wear a hijab freely. Masagos’ approach, for one, is problematic—who gets to lead in these discussions if not a committee of like-minded men?

Faisal’s idea of a public debate, on the other hand, might be highly idealistic because it involves discussing a plethora of other issues like religious freedom, gender discrimination, employment laws and secularism. Seeing that not everyone is on the same side on a lot of these issues, it might only lead to a drawn-out (and possibly polemical) discourse. Nothing will get solved in the end if it’s all just talk.

But before we get into all that, let’s circle back on Singapore’s brand of secularism.

Under Article 15(4) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore, a person’s freedom of religion can be restricted by a general law relating to public order, public health or morality. The term ‘general law’ mentioned here is not explicitly defined in the Constitution, but may refer to a law that applies to all persons or places belonging to a particular class. In other words, no community can use its religious stance to dictate affairs of the state, be it in the formulation of public policies, making of decisions or enactment of laws. Which is probably why the idea of a public debate or opening up to more diverse voices might be a pipe dream for now.

Sensitive, Divisive or Just a Show of Power?

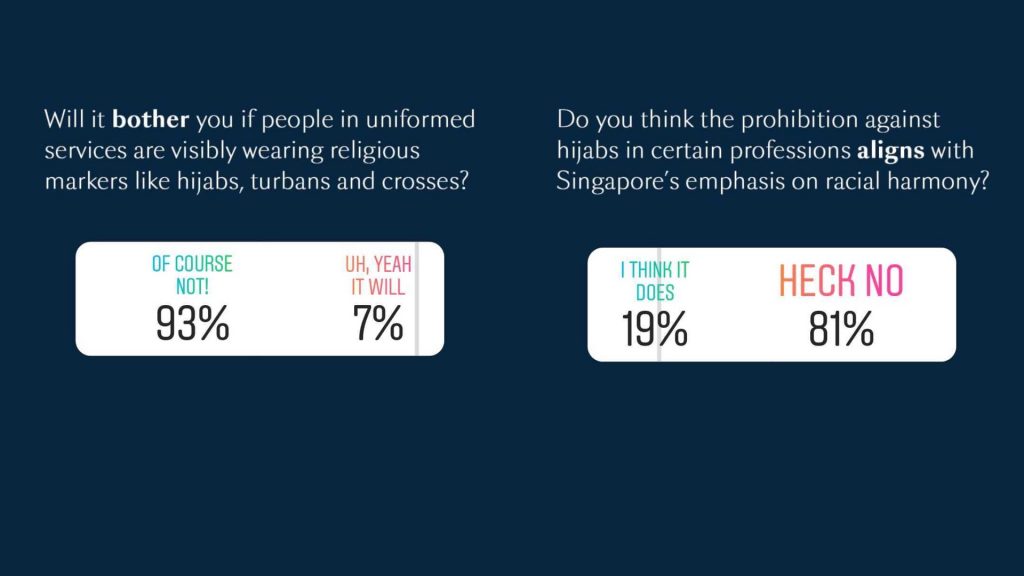

Of course, one cannot rule out the most obvious reason why we’re still stuck debating this issue almost a decade on. On the ground and on the internet, it’s easy to find plenty of people who don’t have an issue with donning the hijab in a uniformed workforce. But on the policy-making level, it’s a different story.

Racial harmony is a fragile thing, and it is in the government’s interest to maintain it. Even if this means having unpleasant debates in Parliament about issues they have yet to quash.

While there are no specific local laws set governing the use of hijabs at work, the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices (TAFEP) has some guidelines for businesses to follow. The guidelines promote principles of applying relevant and objective criteria related to job requirements and can help firms avoid discriminatory staffing practices—including dress codes. But if no representation or a diversity of views is being considered during the hiring process then this too may not benefit someone wearing a hijab.

“Representation” just seems like a novel term being thrown around loosely at this point. Just take a look at the people in power having the conversation. Masagos asserts that the hijab agenda is a sensitive issue to be discussed behind closed doors. Why the issue is “sensitive” he fails to explain. In this hypothetical closed-door discussion, who is going to be present and who will be representing the views of Muslims?

Dr Maliki Osman, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, upholds the stance that the Government has the support of religious scholars and community leaders who “understand that these issues, especially those that involve racial and religious sensitivities, are complex and any decisions on them should not be taken lightly”. His statement could have been more credible if there was transparency on who these supporters are in the first place.

He also commented that uniforms serve to protect a common identity, which in turn strengthens camaraderie. I wouldn’t be the first to point out that even countries like the UK, New Zealand and Canada have hijabis in the workforce.

Let the Women Speak

It doesn’t help that the loudest voices occupying space in this debate have been coming from men. And though Yaacob, Masagos and Faisal may be Malay-Muslim men, making the decision on whether the hijab should be accepted in the workplace is not for them to debate.

Like Sikhs who wear the turban as a part of their faith, the hijab is worn by Muslim women as a religious requirement and expression of their Muslim identity. Being a Muslim woman in hijab means facing unnecessary scrutiny and judgement on their appearance and sometimes, ability.

In the anthology, Perempuan: Muslim women in Singapore speak out, there are accounts of comments being passed in the workplace pertaining to the hijab (“You look like Halimah Yaacob” and “I thought Malay who wear this one (gestures to hijab) all can get along one”). These inconvenient incidents can put more on more stress mentally and emotionally to overcome the biases they may face at the workplace.

Local online platform and community Beyond The Hijab has also done a great job promoting issues faced by Muslim women in Singapore. There, women are free to voice their opinions and experiences in a safe space. A quick glance at their Instagram page, and you will find that there are so many levels of discrimination Muslim women face beyond just the workplace. The group aims to “interrogate the uncomfortable”, and it really is an uncomfortable issue.

In the public sphere, some women are also using their platform to show solidarity. In 2020, when Nurin Jazlina Mahbob was told she could not wear a hijab while working at a pop-up booth at Tangs, it caused an uproar and the hashtag #BoycottTangs circulated widely on the internet. It also warranted a response by Halimah Yacob, the country’s first female president who wears the hijab herself saying that there is “no place” for discrimination.

Worker’s Party MP Raeesah Khan said in a 2020 Parliament session: “Workers looking to make an honest living to support their families should not have to face employment discrimination in the job market because of their age, gender or race, and certainly should not be discriminated because they wear a hijab. We must legislate to this end, not only because fostering an inclusive job market for Singaporean workers makes economic sense, but also simply because this is the right to do.”

Solidarity within the community is always a powerful force. While there are support groups, communities, and outspoken individuals fighting for representation or to be heard, several people we spoke to for this article declined to speak or have their names and professions publicised.

Not only are the voices of Muslim women missing, but the Parliamentary debates also fail to bring to light the intersectional subjectivities of the issue. Firstly, it is an experience only Muslim women face. Secondly, are voices of women considered secondary in this public debate?

The hijab is worn by Muslim women, and it should be Muslim women leading the conversation.

No Space for Discrimination

But the most prominent thing that Masagos and all the men in Parliament seem to be skirting around is that at the heart of it, the hijab issue is more of a racial one rather than a political one. Do you really think your favourite nasi padang auntie is wearing the hijab as a political statement?

Instead of debating endlessly over allowing hijabs in uniformed services, why aren’t we addressing the reasons why some people still perceive that women wearing tudungs aren’t fit for the job? It raises questions about deeply-entrenched ideas about the Malay-Muslim community, and how there still is the perception that they belong in certain jobs more than others.

Not to mention that this is an issue that affects only minority Muslim women here. There is no intent or context in these exchanges in Parliament to say that these decisions have been made with the consideration of women’s—Muslim and hijab-wearing—voices and opinions. As long as we aren’t seeing Muslim women publicly involved in the talks, we’ll probably continue having this discourse in the decades to come.

Not allowing it in specific workplace roles also brings up certain classist undertones—doctors and nurses work in the same field but only nurses are not allowed the hijab to deter patients’ preferences. Not allowing the hijab in fields like nursing and law enforcement also deters some groups from applying for a job they might be fully qualified for.

In the end, it is pretty ironic that the hijab is a misconceived symbol of oppression, because the only injustice here is the visible lack of actual hijab-wearing women having their say in something that involves them.