2018 has seen the local LGBTQ community through many milestones. In July, the year’s Pink Dot continued to draw snaking crowds in Hong Lim Park despite an outright ban on foreign participants and fervent disagreement from many local citizens. In September, debates sparked online after India’s landmark overturn of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a vestigial law from colonial times forbidding sexual acts between men. In November, The T Project opened Singapore’s very first community centre for trans youths. Finally, in December, the High Court allowed one father in a local gay couple to adopt his 5-year-old surrogate son, creating leeway for the pair and the child to be recognised as a family unit in Singapore.

Issues regarding the treatment of LGBTQ individuals in Singapore continue to be a source of contention, and it remains to be seen if the tide will turn in their favour. One thing for certain though, is that the LGBTQ community is now more visible than ever. LGBTQ issues show no sign of disappearing from our radar, and as the conversation goes on, what questions do we have to answer, and how should we answer as Singaporeans?

As another year begins to unfold, how do we move forward?

If last year’s heated responses to the Section 377A debate were any indication, we’re off to a rough start. Discourse tends to divide Singaporeans into simplistic ‘for’ and ‘against’ camps, with local arguments mimicking conflict in now-fraught American identity politics. In this tug-of-war, people are either liberal snowflakes or backward conservatives, with no room for understanding alternative or nuanced perspectives.

Yet Singapore is vastly different from the USA in almost every aspect. We hail from different geographies and histories. Perhaps our answers don’t lie on the midway point, and the liberal-conservative spectrum should be discarded altogether.

Naturally, this invited backlash from citizens concerned about the social well-being of the state. On 13th September 2018, the National Council of Churches of Singapore (NCCS) released a public statement denouncing the movement. The statement cited that homosexual acts are a “perversion of the way in which God has ordered human sexual relationships”, and that the repeal of Section 377A would bring on “undesirable moral and social consequences”.

The statement reinforced the widely held perception that religion was at absolute odds with the LGBTQ community. And so the narrative goes: the modern vs the traditional, the faithless vs the religious.

Yet shortly after, on 30th September, Lim Phang Hong, the president of the Buddhist Fellowship, released his own statement on Facebook. He writes:

“In [a] spirit of care, empathy and compassion, I support the repealing of any law which criminalises, discriminates or marginalises particular groups. We seek to reconcile marginalised communities with society, in a way that promotes respect and harmony across different communities in Singapore and the world.”

These words should have been ground-breaking. They were words of affirmation for the LGBTQ community from a local (check) religious (check) authority (check), and a handful of national news outlets, including the Straits Times and The New Paper, covered the story. Following this, one Reddit thread sprung up on the topic, with the last comments dating from 3 months ago.

Aside from these brief reportings and mentions, the Buddhist Fellowship’s statement didn’t seem to make waves in local debate. Instead, as necessitated in the era of byte-sized news and infinite scrolling, Lim Phang Hong’s words were drowned out with time.

Unsurprisingly, the story was too much of a misfit. It didn’t align itself with the theatrics we’ve staged so far. People are either liberals who champion inclusivity ad nauseam, or conservatives—the supposed silent majority and valiant guards of society’s traditions. It didn’t make any sense for a religious figure to step out and challenge the very concept of the divide.

In our preoccupation with organised outrage, we’ve neglected to look towards each other and consider the complex shades of humanity we have here in Singapore.

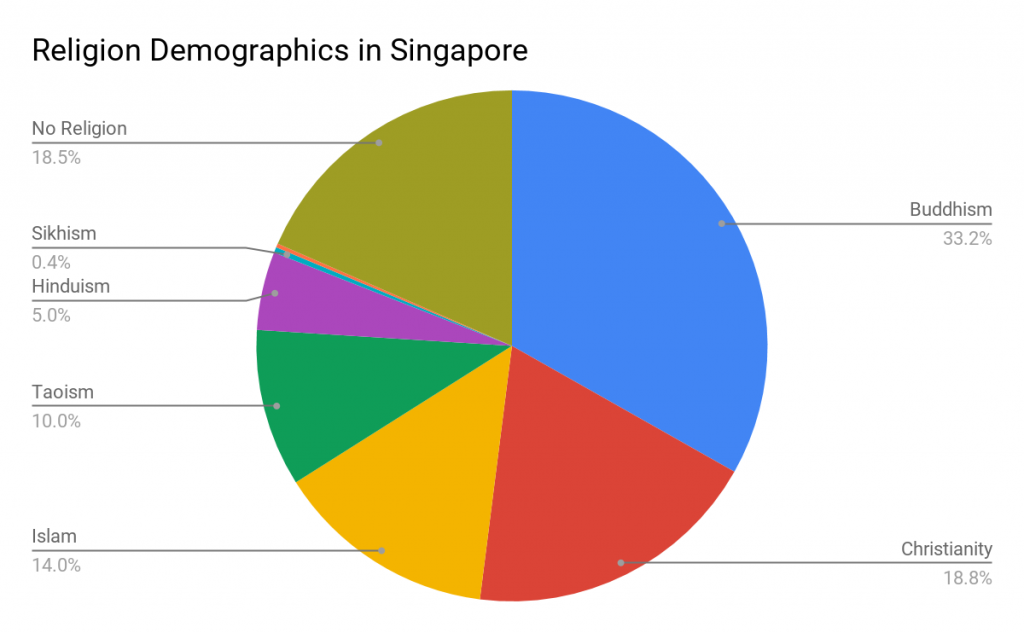

Singapore is a country of multidimensional faiths, and any serious national conversation on the social good has to take these varied viewpoints into consideration. Keeping local discussions local has always been a prime concern for people with skin in the game.

When I spoke to several representatives of local Buddhists about their religion and their approach to harmonious living in Singapore, a local Dhamma teacher had these words to share:

“As practicing Buddhists we follow the eightfold path. We don’t hold judgment for others and we understand that every mind has the capacity for greed or nastiness. We treat others the way we ourselves want to be treated, with empathy.”

The eightfold path summarises the eight practices that people should embody to live nobly: the right understanding, thought, speech, conduct, livelihood, mental effort, mindfulness and concentration.

Angie Chew, the former secretary of Buddhist Congress, further stresses, “Buddhism is not meant to be a religion of faith but of practice … This practice has to be supported by the development of loving kindness for all beings. ‘All beings’ means being inclusive and involves letting go of discrimination, prejudices and resentment. ‘Being inclusive’ means we accept people who are poor or rich, female or male, small or big, homosexual or heterosexual, brown, yellow or white.”

Granted, local Buddhism is not a single, monolithic block, and may be influenced by an individual Buddhist’s personal sentiments. But the fundamentals of the practice advocate for peaceful living without judgment. The majority religion in Singapore provides the philosophical groundwork not just for accepting people of different sexualities into society, but for thriving alongside other faiths.

Eileena Lee, a Buddhist from the local LGBTQ community that we spoke to, attended a convent school in her youth and expressed that her faith was nurtured by a Christian friend who bought her Buddhist books. She stresses, “Religion is personal. There are people who are homophobic, but don’t impose your perception of your faith on others. It’s like vegetarians forcing other people to be vegetarian.”

Two things were simultaneously true. One, because homosexuality was portrayed as something to be “treated”, the campaign contributed to the climate of judgement shrouding the gay community. Two, it also offered gay Christians the opportunity and designated space, if they so wished, to acknowledge their homosexual inclinations but not act on them.

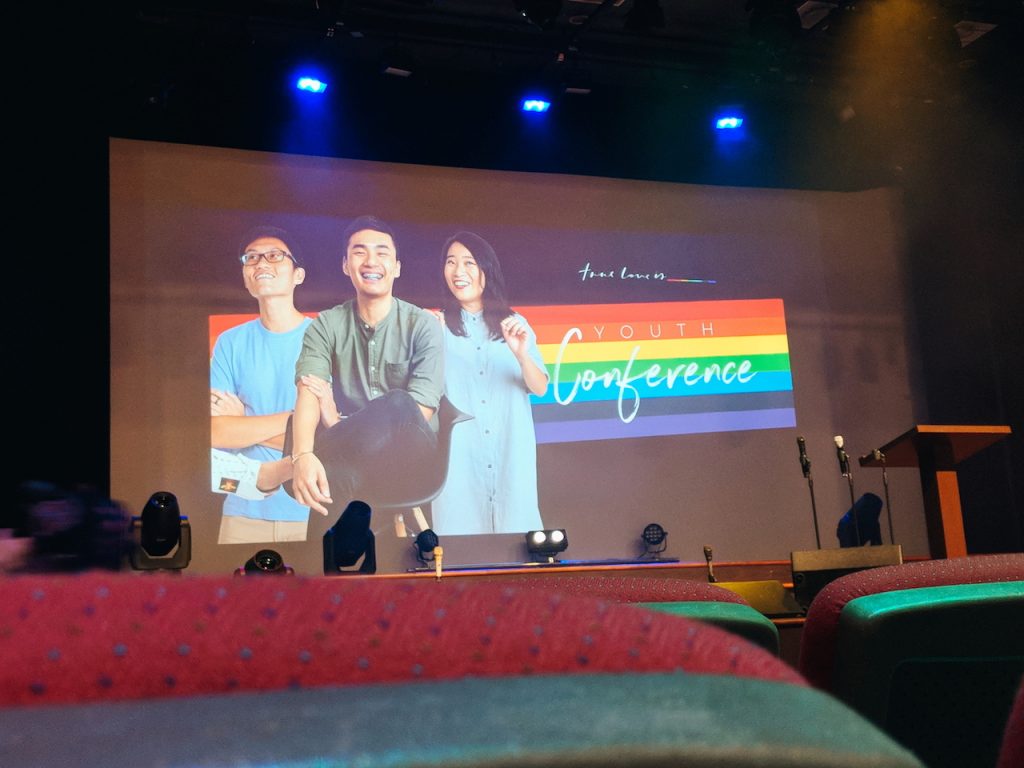

Indeed, it is a problem that the campaign was detrimental to the recognition of homosexuality as a legitimate sexual orientation. The campaign’s target audience was their own Christian community, but the campaign was highly visible and its values inadvertently encroached on our understanding of secular society. Young people, especially those who have been alienated by virtue of their sexual orientation or presentation, are vulnerable, and may be pressured into making life choices they are uncomfortable with.

But in the Buddhist spirit of empathy and harmonious living, all Singaporeans should accept that gay Christians have the choice to reconcile their faith and personal convictions in a way they see fit. It is valid, within their own religion, to provide that space, and that space can take on many forms. It may be a church that rejects the idea that homosexuality is sinful, like Free Community Church, and it could be a programme that allows someone to acknowledge their sexual inclinations but not act on them, like truelove.is.

Sexuality is personal, bodies are personal, and religion is personal.

What does this mean as we move forward in our conversation as a nation?

Singapore is a diverse country. Any argument that divides the country into two clean halves should arouse our suspicion. Discourse on LGBTQ rights in Singapore would be more constructive if we weren’t constantly picking sides and overlooking our capacity as individuals to hold nuanced views on our own faiths and sexualities.

An elderly Christian woman might support the idea of same-sex marriage if she has a homosexual granddaughter. A young atheist might frown upon the idea because he believes that the very concept of marriage should be challenged, and not regarded as the ultimate aspiration for gay rights. We are not diverse in the same way that skittles are colourful; skittles of the same colour always taste the same. We are diverse like a library of books. We hold complex stories, and to each their own.