Not only that, online chatter among Singaporeans seemed divisive. A portion portrayed Malaysians as foreigners coming into ‘our country’ to take our bread-and-butter, earn income three times the rate of their home currency, all while jamming up the checkpoints at Tuas and the Causeway. Others, however, were encouraging, even opening their homes and living spaces for these displaced workers to stay, providing food and amenities.

We found 7 Malaysians who shared their stories with us:

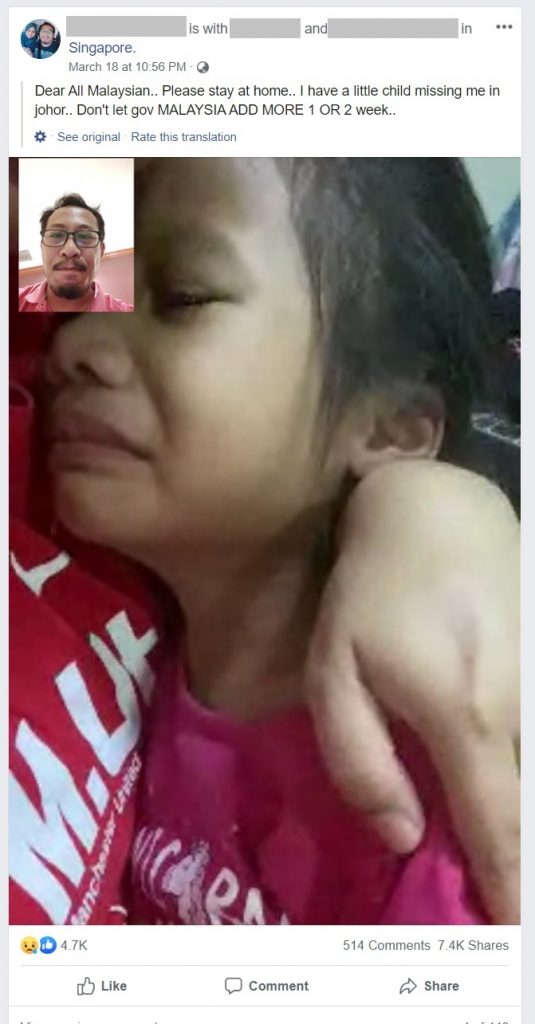

“Malaysians in Malaysia must follow government rules to stay home. (If they don’t follow), the government may extend another 1 or 2 weeks. What Malaysia is doing now (with the Movement Control Order) is good for both countries. So Malaysians back home, please, please, stay at home,” pleads Abdul Mazlan*, 36, one of the seven we spoke to.

Mazlan has been stuck in Singapore since 18 March, and he can’t go home till the MCO is lifted on 31 March (now, it seems probable this will be extended). Mazlan works as a Senior Manager in an interior design firm in Singapore.

Since 2010, he’s taken the early morning and late evening bus to and from the Causeway every weekday. Now, his only connection to his home in Johor Bahru is his heart-wrenching video calls with his 8-year-old daughter, whom he misses dearly.

“Singapore food is okay, but not as good compared to my wife’s cooking lah. But I can survive and live with local Singaporean food, of course,” he added, after some thought.

Is he concerned about some Singaporeans’ attitudes towards Malaysians coming over and “earning 3 times their local currency”?

“Some (of us) will agree, some won’t. For me, I work here because I need to learn and improve my aptitude and skills, due to international standards of industry here.”

“What can I do? I have to face it. I’ve never stayed in Singapore before,” he says. Yet Eda is appreciative of some of the kindness he’s seen from fellow Singaporeans. In a Facebook group he’s in, a Singaporean invited Eda to Blk 682C Woodlands on 22 March, as there was extra bungkus of Nasi Briyani left over from his son’s wedding. Eda was grateful.

“Terbaik …” he chimed, showing me the invitation (terbaik means very good in Malay).

Mohd Zain*, a 37-year-old technician in a pharmaceutical manufacturing firm also had nothing but praise for Singapore and his company (he declines to reveal its name).

“Living conditions are good, thanks to my company and the Singapore government. The food here is not so bad but I really miss my wife’s asam pedas.”

“Expenses here are a bit higher than staying in Malaysia. I am still searching for a self-serve laundry service, but finding my way around Singapore shouldn’t be a problem,” he told me. He’s currently staying at the Grand Park City Hall Hotel and has been working here for 6 years.

Zain too misses his wife and children. He has three daughters (aged 8 months and 10 and 11 years old) and an 8-year-old son (whom he proudly declares is really smart).

“Through this period, I have to be strong (for them). Hopefully, Malaysia will open its border as soon as possible. I don’t know how to describe (the border closing) … just move on and take all this as a challenge, always pray and wait for good news from our government.”

25-years old and single, Jin isn’t feeling as homesick as Mazlan, Eda, or Zain.

“On the first day, the company provided us with McDonald’s dinner. I managed to wash my clothes once, so I have to repeat it again today. After five days, my colleagues and I found a cheap place nearer to the hotel to pack our meals, like for dinner. We usually eat near where we work, which is in the Kranji area.”

At the same time, Jin wishes the Malaysian government had done something else instead of closing the border. To him, it is difficult to regulate and control everyone’s movements on such a large scale.

“They’re not going to be able to control crowds. Instead, the Malaysian government should look into widespread disinfection and treatment. Now they are just trying to catch something here, then catch something there next. I don’t think it’s effective for a country so large.”

I asked Jin if he’s faced any backlash from Singaporeans questioning his choice to remain in Singapore instead of staying back in JB.

He tells me frankly, “It’s three times the wages in my home country. In this world, you look at me, I look at you. (Neither of us) have real experience about what each of us do. Everyone’s free to use words to say three times is good. But really, it’s just good enough to spend. Even now, going up and down the Causeway is the same. Because now, in Johor Bahru, the cost of living is almost the same as Singapore. Most of us locals are just living day by day.”

When the MCO came into effect, there was a mad scramble for accommodation. Many of the Malaysians I’ve spoken to are generally well taken care of by the Singapore companies they work for. They are grateful the companies were willing to make efforts to make calls, find and pay for lodging; some even helping with food and daily expenses. It makes them feel appreciated.

Some of this relief has also come through the Singapore government. On the evening of 17 March, just hours before Malaysia shut its borders, Singapore’s Manpower Ministry declared a S$50 allowance per worker per night for 14 nights, paid to affected firms, as a way to cover extra costs. This is on top of assisting displaced workers with finding short-term housing at hotels, dormitories, HDB flats, and private residences.

Because now, in Johor Bahru, the cost of living is almost the same as Singapore. Most of us locals are just living day by day.

However, not all Malaysians are so lucky to have companies providing shelter, let alone food and daily expenses. Some Malaysians I spoke to shared horror stories of sub-par standards of living despite having worked for their companies for years. We’ve seen the news of workers sleeping at Kranji MRT station, so what could be worse than that?

The issue isn’t just about not having a place to stay, but how some Singapore companies perceive their staff, and the welfare they provide when their staff needs them most.

Miss Chi*, 40, works as a contract staff providing customer service at a nursing home in Singapore. Her contract is renewed every two years. On the day the MCO came into effect, she left her young children in the care of her mother in Malaysia to rough it out for two weeks here. Little did she expect that the accommodation her company provided was going to be a nightmare.

Situated in Telok Kurau, she had to share a room with 5 other people. Not only that, her mattress was filled with bed bugs and the shower facility was filthy.

“Most of my full-time colleagues and other Malaysian friends got hotels. This is the worst I’ve seen so far. I feel really disappointed with our management. I have no words. I mean, yes, I may be a contract staff, but this shouldn’t be the way a company perceives and treats me.”

For daily food and transport money, Miss Chi relies on her brother, who’s working in a different company in Singapore. She is doing this as a matter of survival. It’s also for her children, and to repay her loans.

“I miss my kids. If I don’t work, there’s no money and I’ll be in a difficult situation.”

Another Malaysian who hasn’t been so fortunate is Mr. Tung*. Born in Batu Pahat, Malaysia, Tung is 35-years-old and operates a lorry crane for a construction firm. He was only given a place to stay, which he tells me is nothing more than a wooden board on a bed-frame (with fans and a common cabinet to be shared among those in the room).

He has to pay for everything else (expenses, food, laundry, travel), himself.

“Everyone of us has to eat out,” he says in Mandarin, “I’ve been working for almost two years, and this is what I get.” Five days after I spoke to Tung, I checked on him again. He tells me he’s now sleeping in his lorry.

I could hear the resignation in his voice: “I’m the only one who got out (through the Causeway). The rest of my family is in Malaysia. People’s livelihood is already non-existent, so I’ve nothing more to say to that.”

Finally, 26-year-old Wadia* works as an inspection engineer in a factory here in Singapore. He stays in Gelang Patah with his wife and one-year-old baby girl. Two of his hobbies are riding his motorcycle and playing DOTA. These days, he can do neither.

“I’m sharing a hostel room with three others in Geylang right now. The company is giving me an additional S$20 a day for expenses. I’ve heard other companies (like my friend’s), giving S$50 a day and free hotel stay. For me, I’m paying for my own daily travels with my own savings. The time it takes for me to get to my workplace from Geylang is about 40 minutes.”

To feed himself without overspending the allowance money, he’s been snacking on just bread and water. “I cannot afford to buy food. I need to save now. This is because we don’t know when we can go back to Malaysia. At lunch, I buy my meal for S$3. Laundry here is around S$8. I might save up and go to my friend’s hotel to wash my clothes there instead.

“I’m also worried about my family and my baby girl back home. Everyday I call my wife, asking her to stay home and be safe. I explained to her the border has to be closed because Malaysia is afraid of whoever is working in Singapore having the virus and bringing it into the country. I also have to assure her to be careful about thieves, especially when they come by my family home. She needs to make sure she locks everything.”

Wadia is sad that he cannot go back to Malaysia. Before he left Johor, he prepared food and necessities to last a couple of weeks for his wife and baby girl.

“I just hope there is no increase in Covid-19 cases in Singapore, or Malaysia.”

When I asked Wadia what he hoped for in the days ahead, he remained pensive: “I think the Muslim Hari Raya celebrations might be cancelled this year. We don’t know when we can kill this virus. It’s hard to know over these next few days. The symptoms don’t show up and usually take more than a few days to see.”

And what about Singaporeans here? Have they been friendly to him, considering he’s earning Singapore dollars and sending money home to Malaysia?

For a 26-year-old, he has a broad perspective on things.

“I just tell myself to be positive. Take it positively. Many Singaporeans also come into Malaysia to shop. We don’t say anything about that. Just a few lah, not all of them are bad. Malaysia also has bad people. So far, the Singaporeans I’ve met here are friendly and okay. I have no complaints. I just want to focus on my job and get home to my family when the MCO is lifted.”

* names have been changed

We would like to thank everyone for their responses and offers. We have been sharing alternative housing options to our Malaysian interviewees. Thank you.