One of the most common stereotypes in Singapore is the ‘Lepak Malay Guy’.

I don’t know if this is ‘woke’ or appropriate for a Chinese person to be writing about, but the archetype surely exists. When the word ‘lepak’ was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2013, the viral vigilantes of SMRT Feedback Ltd immediately posted: “Malays are so lepak,” as an example of how to use the word in a proper sentence.

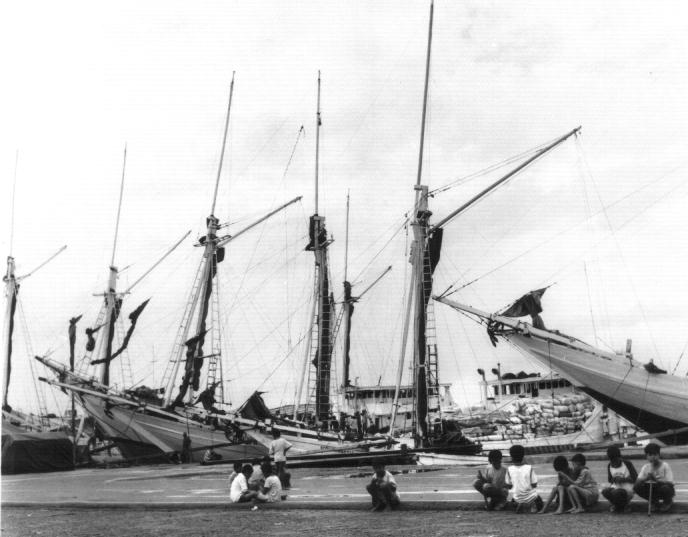

I can furnish you with more examples, but that would be unnecessary. Anyone who has lived in Singapore for any amount of time will recognise the familiar archetype of the chill, lazy Malay dude, who just wants to hang out at the void deck and smoke Marlboro reds instead of applying himself vigorously (whatever this means).

This is where our problems begin.

‘Lepak’ does not simply mean ‘chill out’ in the Hawaiian surfer dude sense. The archetype carries with it the negative connotations of ‘laziness’, and not everyone uses it ironically for comic purposes. Even in 2018, I’ve encountered army enciks, taxi drivers, civil servants, elite school graduates, and Indonesian-Chinese businessmen who sincerely believe that all Malays are inherently lazy and thus undeserving of employment/success/help.

This is ironic because accepting caricatures at face value is the very definition of intellectual laziness, and a slippery slope towards more serious forms of discrimination.

Hence, it is worthwhile to examine the history of this stereotype, however briefly. After all, denouncing racism is par for the course these days, but I find it entirely pointless if we do not understand how such ideas came to be in the first place.

Contrary to popular belief, the ‘Lepak Malay’ did not just emerge organically from the popular consciousness like mushrooms after rain.

Neither is it an insidious invention by ‘yellow cowards‘ seeking to oppress/exploit other races for economic gain, as some scholars have suggested.

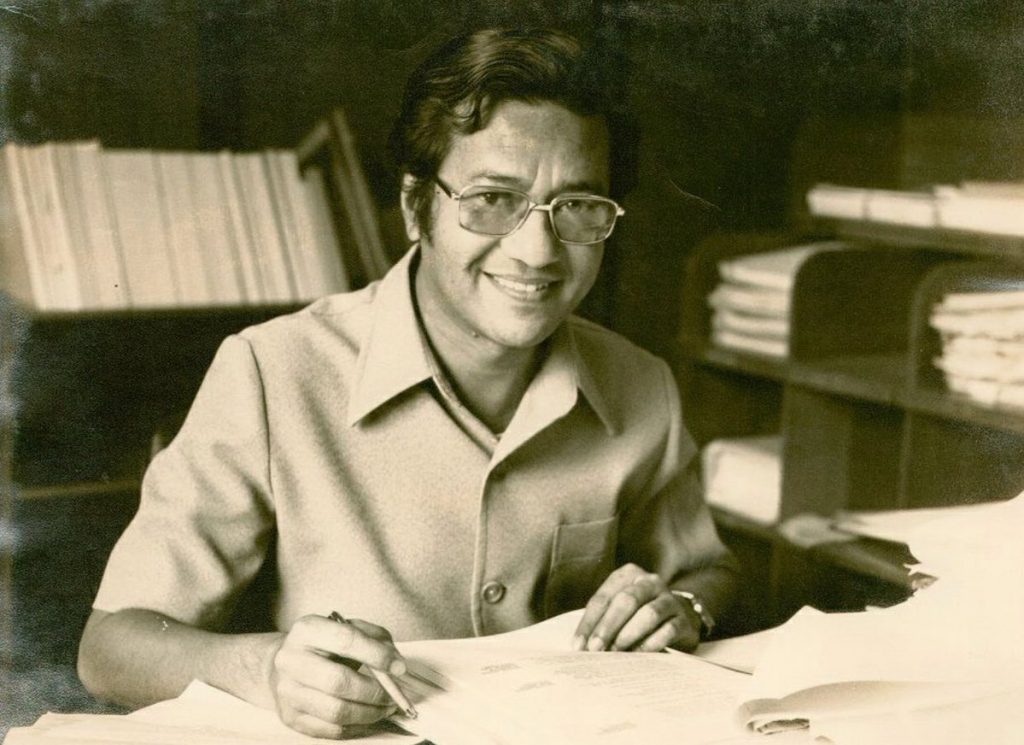

According to the late, celebrated Malaysian Sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas, this ‘myth of the lazy malay’ dates back almost 200 years to colonial times, when the British and the Dutch first realised that Southeast Asia’s resources could make them really, really rich.

In his book The Myth of the Lazy Native, Professor Alatas gives us various examples from the 18th and 19th century, when European observers first began describing Malays with terms like ‘lazy’, ‘indolent’ and ‘disinclined to work’.

Here is Frank Swettenham, British Resident of Selangor, describing the local population. Along with courage, excellent swimming skills, and an absence of ‘servility’, he says: “The leading characteristics of the Malay of every class is an disinclination to work.”

Hugh Clifford, full-time British Resident of Pahang and part-time fiction author, concurs. He writes: “Less than one month’s fitful exertion in twelve, a fish basket in the river or in a swamp, an hour with a casting net in the evening, would supply a man with food. A little more than this and he would have something to sell. Probably that accounts for the Malay’s inherent laziness; that and a climate which inclines the body to ease and rest, the mind to dreamy contemplation rather than to strenuous and persistent toil.”

Mr. Clifford and Swettenham were not alone. Our beloved Sir Stamford Raffles said of the “lazy Malay” that “he is so indolent, that when he has rice, nothing will induce him to work.”.

Other commentators in 1901 have said that “the Malay of the peninsula were the most steadfast loafers on the face of the earth” because “for nine-tenths of his waking hours… he sits on a wooden bench in shade and watches the Chinaman and the Indian build roads and railways.”

As the good professor rightly points out, anyone who does spend 90% of his or her waking hours sitting on a bench would surely have fallen dead by the third week. This is not science or anthropology. These so-called observations are half-baked racist stereotypes born of prejudice and transformed into fact by mindless repetition.

Evidence for the not-lazy and not-lepak Malay are evident in simple facts such as:

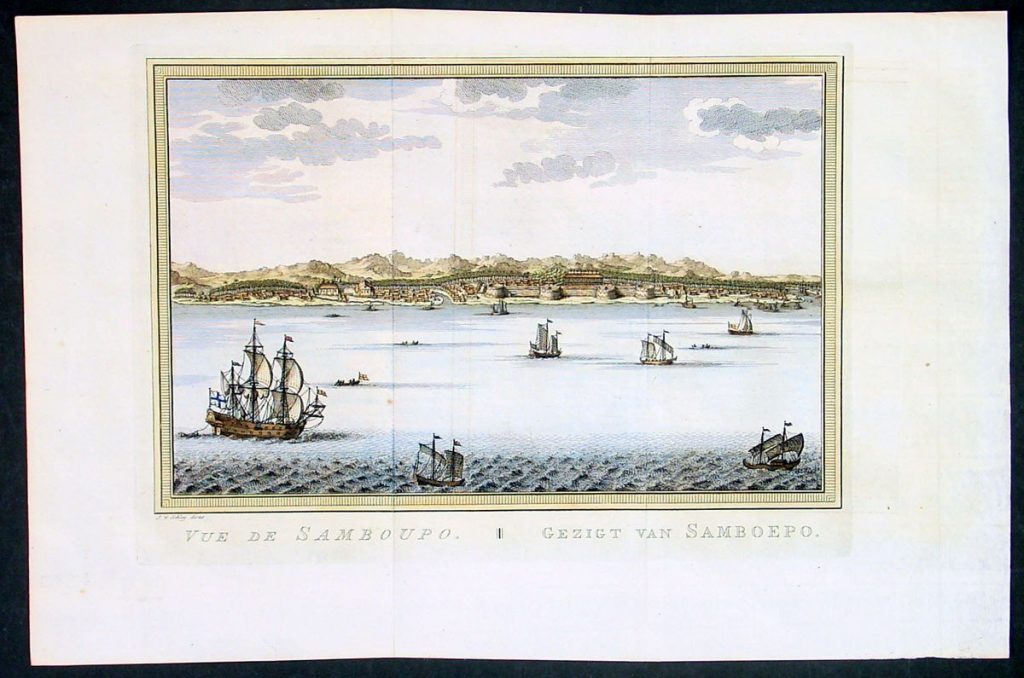

1. The existence of a Malay merchant class, which was only wiped out after the British and Dutch established monopolies in the region.

2. Subsistence agriculture like fishing or padi planting variety was undeniably hard work. Even if it was less visible to the British, who were concentrated in urban areas.

3. The colonialists’ own writings, which are full of statements that contradict their own claims of laziness. If Malays were indeed lazy, they certainly would not make for ‘industrious’ or ‘superior’ naval crew, nor would it make any sense for them to engage in constant war with colonising forces.

But if such stereotypes are evidently false, then how did they come about?

The answer lies in the limited experience and narrow interests of our former colonial masters, explains Professor Alatas. Your secondary-school social studies textbook kindly forgets to mention that Raffles and co. landed in Singapore for one purpose and one purpose only: to make bank. Trading ports, infrastructure, plantations and other local institutions all served to fuel the British economy and enrich Her Majesty in London.

The Malay population, who mostly refused to participate in this colonial exploitation, were thus labelled ‘lazy’.

For the crime of refusing to be a plantation slave, or to risk their lives for meagre wages in a mine shaft, they were considered ‘essentially indolent’ by the British government, who were no doubt pissed about the labour shortage this resistance created. The British also compared Malays unfavourably to the more ‘industrious’ and ‘indispensable’ Chinese and Indian labourers, seeming to forget that Chinese and Indian immigrants were slaves in everything but name under the system of indentured labour.

The truth is, no sane person today would agree to do the kind of work done by Chinese and Indian coolies in the 1800s. If the same standards for laziness were still applied in 2018, everyone would be a steadfast loafer and proud of it. The Malay independent farmers who had a choice made the logical choice of ‘fuck no’ when asked to kill themselves as coolies, and were consequently smeared as ‘lazy’.

Over time, this ‘lazy’ stereotype slowly become ‘The Truth’ with a capital ‘T’ because there was no way to refute it. Or as Professor Nur Amali Ibrahim summarises: “This stereotyped image steadily acquired consistency, authority and the irrefutable immediacy of objective reality.”

All of the above happened in the 1800s and early 1900s. It does not explain how the ‘Lepak Malay’ stereotype survived till modern times.

The answer is simple but uncomfortable: it has been around for so long that everyone took it as Gospel.

After the British bade us farewell, they passed this stereotype into the capable hands of Malaysia’s once and future Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir, who became most vocal proponent of the ‘laziness’ stereotype. In his controversial 1970 book The Malay Dilemma, he makes statements like “Doing nothing, or sipping coffee, or talking is almost a Malay national habit,” and there are constant references to the essential ‘easygoing’ character of his own race.

As recently as 2014, he told reporters in an interview: ‘If anyone asked me today, I would have to say that Malays are lazy.”

“The Malays are lazy, they are not interested in studying and revising. If we go to the universities, 70 per cent of the students are women, where are the men? They prefer to become Mat Rempit (Malay motorcycle gang members), that is why I said they are lazy,” he further elaborated.

Mahathir’s intentions were, of course, entirely different from Raffles or Clifford. Then (and now), he was seeking to improve the socioeconomic standing of Malay Malaysians, and the stereotype was a means to justify his affirmative action policies.

Unfortunately, it is also impossible to deny that he was parroting a hundred-year-old ethnic stereotype.

But the Singaporeans who are patting themselves on the back right now for being progressive/enlightened should refrain from doing so. Our first-generation political leaders disagreed with Mahathir on almost everything, but not on the laziness myth.

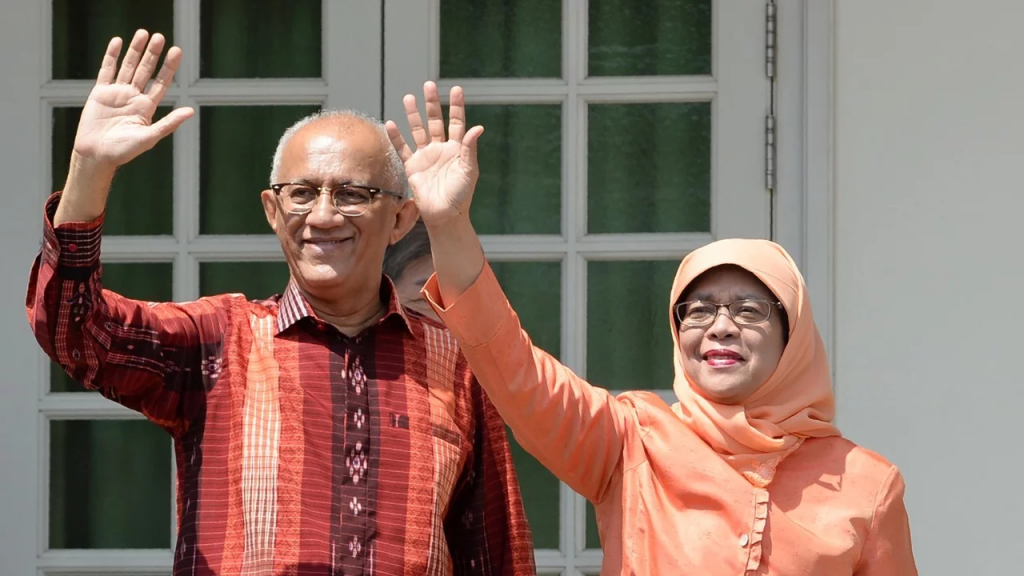

In Singapore, the myth of the lazy native got a makeover and transformed itself into the ‘cultural deficit theory’. As Professor Lily Zubaidah Rahim (niece of Yusof Ishak) writes in The Singapore Dilemma, this ‘unflattering cultural characterisation’ was widely propagated in post-independence Singapore by both Malay and non-Malay politicians, as a means of explaining away the inequalities/gaps that emerged in our so-called meritocracy.

Our late Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew was extremely candid about his views. In his book, Conversations with Lee Kuan Yew, he went on record to say: “We could not have held the society together if we had not made adjustments to the system that gives the Malays, although they are not as hardworking and capable as the other races, a fair share of the cake.”

His view was echoed in milder terms by other politicians like MP Sidek Saniff and Parliamentary Secretary Yatiman Yusof, who scolded Singaporean Malays for their “crutch mentality” and their reliance on the government to “do this and do that for them”.

Dr Rahim traces these contemporary attitudes back to the “colonial and orientalist discourse on Malays”. In simpler words, what was once an European excuse for colonisation went unexamined for so many years that it slowly fossilised into fact. What started as British propaganda went unchallenged for so long that it became a widely-accepted ‘truth’ on both sides of the Causeway.

So where does all this leave us now?

In 2018, few sensible people (I hope) subscribe wholesale to such ideas. In public view, the ‘lepak’ trope has been mostly consigned to ironic hipster merchandise or to comic punchlines. In Parliament, no 4G leader would be caught dead making such a statement, and even Dr. Mahathir has distanced himself from such views in the recent election.

However, the stereotype remains at large. We mostly avoid it in polite conversation but we’ve yet to put it to rest. Although the Straits Times no longer publishes headlines comparing achievement by race, there is also no evidence that socioeconomic parity is mission accomplished.

Likewise, the unpleasant stereotype raises its head every now and then, such as during last year’s Presidential election, when there were snorts of disbelief in response to the criteria of a) Malay, and b) Chief Executive of a company with $500 million in shareholder equity.

Malay Chief Executive? Good luck with that.

The problems persist because we have never come to terms with our own history. Cultural stereotypes were never called out for being stereotypes, but instead became a crude explanation for disparities and flawed policies.

Such stereotypes are not just mistaken or hurtful, they’re lazy.

Know something we don’t? Have something to say about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.