All photography by Zachary Tang for Rice Media

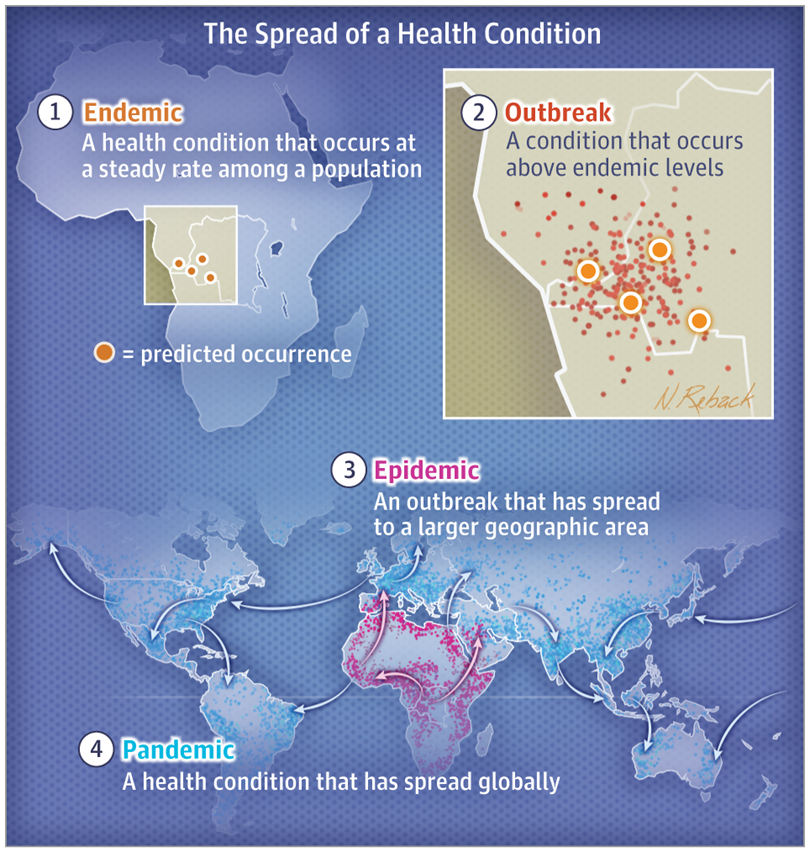

There’s finally some light at the end of the tunnel, if statements made by our political leaders are anything to go by. Their messages have been clear: Covid-19 is endemic, and we must learn to live with it.

The first indications came from Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who on May 31 spoke about “test, trace, and vax” in the new normal. Then we had a joint newspaper op-ed by the ministers on the multi-ministry taskforce, who set out a roadmap towards normalcy while living with the virus. Most recently, Finance Minister Lawrence Wong reiterated in Parliament about Covid-19 becoming endemic.

But what does an infectious disease expert make of these plans by the government to move into another new normal? As experts, they know more about the virus than political leaders. Are they on the same page, then?

We interviewed Professor Paul Tambyah, who is the President of the Asia Pacific Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infection, and asked him how the “endemic new normal” should be reflected in our health policies—specifically about vaccination and the gradual opening-up of our society.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Sean Lim: When should we declare that Covid-19 is endemic? Should we follow the WHO’s guideline, or at what point can we do that?

Prof Tambyah: It’s not for us to declare when the pandemic became endemic; the World Health Organisation could have done this about six months ago. Viruses become endemic when they reach most countries and are established. Very few have had 28 days without a locally transmitted case.

SL: How should this “endemic” state be reflected in our health policies?

PT: Like diseases which are endemic here, such as dengue or HIV, we should seek to diagnose all cases, treat those at risk of complications, and make significant efforts to prevent them (although in the case of HIV, I think we could allow condom ads). These health policies have done well in managing those diseases, though these could be better.

SL: Was it justified for the government to chase zero community cases? Were they tracking it for too long?

PT: There is intense debate over this in Australia. Many countries have only given up on the “zero Covid” aim recently. Although I wished we had foregone that long ago, I understand why it took the government so long. Even now, people are still hoping for zero cases in Singapore, Australia, and elsewhere so it’s not an easy decision.

SL: What made them “give up the ghost”?

PT: Without any evidence at all, I’d guess the experiences in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea convinced our leaders that it’s impossible to go 28 days without a locally transmitted case. The costs of waiting are simply too high, be it the impact on mental health, small businesses, or elective surgeries.

SL: Since Ong Ye Kung became the health minister, what has he done right so far in handling the pandemic, and what can be improved?

PT: It’s good he realised how useless it is to aim for zero Covid cases. He should probably consider taking a step back and letting the experts—epidemiologists and experts like the NCID directors—take the front stage, just like during the SARS outbreak (severe acute respiratory syndrome). The contrast between the press conferences then and today is striking. The ministerial committee was very much in the background in 2003, making important decisions while the experts explained them.

Stepping up vaccination is good as this has been the only way to eradicate a virus, like smallpox completely. Measles and polio are also on their way out, thanks to vaccines so it’s good to see Minister Ong ramping up vaccinations.

Some activities such as routine-rostered testing of completely-vaccinated individuals should probably be reduced after ensuring the risk of vaccine breakthroughs in these individuals is low.

SL: Having two-third of the population jabbed by National Day—is this goal too optimistic or doable?

PT: That’s realistic, and chances are the rate will be better than that.

SL: What if we don’t reach that goal? Should the economy and social activities still gradually open up?

PT: To acknowledge the virus is endemic, we must accept having cases now and then. What’s important is to stop people from becoming very sick or dying, like in Europe and North America. In the unlikely scenario where we don’t hit the target, I don’t think we’ll need to have more restrictions. We should still open up while getting more people jabbed.

SL: To you, what’s a “calibrated approach” in opening up borders?

PT: It begins with vaccinated persons having some form of verifiable vaccination certificate, like what we do with those from countries where yellow fever is endemic.

The next logical step is having a pilot with Malaysia, like what we have been doing with cargo drivers. This could be expanded to other categories of people, such as those from Johor Bahru who work here and want to get at least a dose of vaccine here. There are many possibilities. They need to be accompanied by careful vaccination programmes and periodic surveillance.

SL: Borders control—is it even useful to classify the risk of travelling to countries according to Centres for Disease Control’s guidelines?

PT: No. We have to assume that the virus is endemic worldwide (maybe even in Brunei and New Zealand where the virus is largely under control) and just ask for proof of vaccination. That’s what the Saudis have been doing for pilgrims travelling for the Haj and Umrah, regardless of whether they come from high endemicity or low endemicity countries for meningitis.

SL: What more can be done for those who cannot be vaccinated?

PT: Most countries have done well in vaccinating those who are eligible, ramping up testing, and identifying sick patients who need to be hospitalised. That’s what we’ll continue to do with the handful of individuals who can’t be vaccinated. There are also other ways, such as using the povidone-iodine throat spray, which was found to be useful in the migrant workers’ dormitories.

SL: Regarding the open letter by numerous doctors, which was refuted by MOH, what do you think is the doctors’ agenda? Do you agree with them? Chinese-daily Lianhe Zaobao said in an editorial that what the doctors did was out of the spirit of curiosity and that spirit is part of science. Do you agree?

PT: These vaccines are brand new—barely six months old. The technology in the viral vector and mRNA vaccines has never been used in a vaccine before, so it’s understandable to have concerns.

There are no long-term safety data in humans or animals, although human data are being provided to the regulators regularly. Nobody knows what will happen a year after the mRNA vaccination, and we will not know until Dec 2021. The data so far is very promising, other than the news about transient heart inflammation in some young men and rare blood clots. Overall, the vaccine seems relatively safe over the last six months.

Scientists and clinicians regularly debate over vaccines and it’s important to listen to both sides and evaluate the data objectively. Let me give you an example: In the case of polio, Professors Salk and Sabin hated each other and rubbished each other’s polio vaccines. Two infectious diseases specialists whom I respect greatly had very divergent views on the smallpox vaccination campaign for healthcare workers following the 9/11 attacks. Having such medical debates and arguments are normal.

SL: When can we stop wearing masks?

PT: Hopefully before the end of 2021 when we cross the 75 per cent vaccination mark and have very few community or imported cases. That is similar to California and New York, where they did not have a rebound in cases.

SL: Regarding the backlash against mRNA vaccines among some segments, is that based on science? Are there justifications for that?

PT: Nobody knows what will happen a year after a mRNA vaccination. What’s reassuring is that data from the last four to six months seems promising, though we haven’t seen peer-reviewed publications on medium-term safety yet.

SL: Why would Singaporeans queue for Sinovac? Is there vaccine nationalism among some segments?

PT: Singaporeans are pragmatic. What I’d assume is that many queuing for Sinovac want to travel to mainland China and the Chinese authorities only recognise Sinovac and Sinopharm for a reduced quarantine upon arrival.

SL: Has the government done right in not including Sinovac into the national programme and making them available only via the Special Access Route?

PT: The WHO approval for Sinovac, having gone through a rigorous assessment, has probably reassured MOH that nothing untoward will happen with a limited rollout of that vaccine.

However, Singapore has stringent procedures for drug approvals which the Sinovac company was not prepared to adhere to. The company had some issues quite apart from its products. It was listed on the NASDAQ stock market index and had its trading suspended since 2019 due to some complications.

The issue of drug approval (even if recommended by WHO but not approved in Singapore) isn’t new. For example, the drug of choice for treating malaria, Artemisinin, isn’t licensed here because the company which makes it is not ready to go through the paperwork. Doctors who need to treat patients with severe malaria have to complete paperwork to obtain the drug. While it’s still troublesome, the process has been sped up with provisions made, so these patients are not deprived of treatment.

SL: Is it fair for the government to allocate Sinovac to the private clinics and allow them to charge people for it since some Singaporeans can only use Sinovac for health reasons?

PT: The government has said that those who need Sinovac for medical reasons would have their cost covered.

SL: After we enter a state of endemicity, how often should we get booster shots?

PT: There are strong indications that immunity from vaccination or natural infection lasts for more than a decade. A group from Duke-NUS Medical School has shown that those who had recovered from SARS can recognise and destroy the Covid-19 virus 17 years after the infection.

As such, I think it’s unlikely for us to need booster shots. They may be required in outbreaks or for high-risk professions, though. This is the case for MMR vaccines, which are sometimes given as a third dose during outbreaks, or Hepatitis B booster shots given to some high-risk healthcare workers with lowered immunity. Most people do fine with two doses of MMR and three doses of Hepatitis B vaccination.

SL: Is the rate of mutation of the virus swift and beyond what authorities can control for vaccines? Is the rate of mutation we see today natural?

PT: The rate of mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 is similar to what we would expect of a coronavirus but much slower than an influenza virus, for example. Just like other viruses, what happens is that a more contagious and less deadly strain had taken over recently, similar to last year when the “father” of the delta strain—the D614G mutant—appeared and replaced all other strains.

This process is also done in the laboratory to produce weakened strains of the virus as we pass the virus through successive generations of lab animals.

SL: On a related note, will it affect us from reaching the state of endemicity if we always have variants, or are we doomed since we’ll have to constantly play catch-up?

PT: What’s likely is that the virus will mutate further, with the appearance of more contagious but less deadly variants. This was what happened with all pandemic viruses, including the H1N1 virus, which was circulating for the last decade, until last year when like all seasonal influenza, it disappeared.

It’s the same with the deadly “Spanish flu”, which killed many worldwide between 1918-19. It became the dominant circulating strain of influenza from 1920 to 1957 and was finally eliminated with the arrival of H2N2, which Professor Lim Kok Ann first identified in Singapore.

What do you know about Covid-19 becoming endemic? Tell us about it at community@ricemedia.co.

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram. If you have a lead for a story, feedback on our work, or just want to say hi, you can also email us at community@ricemedia.co.