All images by Wu Bingyu (@bingleswu).

ADVERTISEMENT

A couple of months ago, I read that ACRES, the wildlife rescue and rehabilitation charity, was fielding more calls to its 24-hour hotline than ever. Their rescue team was kind enough to let me tag along on two of their shifts, which is how I ended up on— literally— the wildest assignment of my career.

This piece covers the night shift. You can read Part One, which covers the day shift, here.

DAY TWO: NIGHT SHIFT

1830: Feeding time

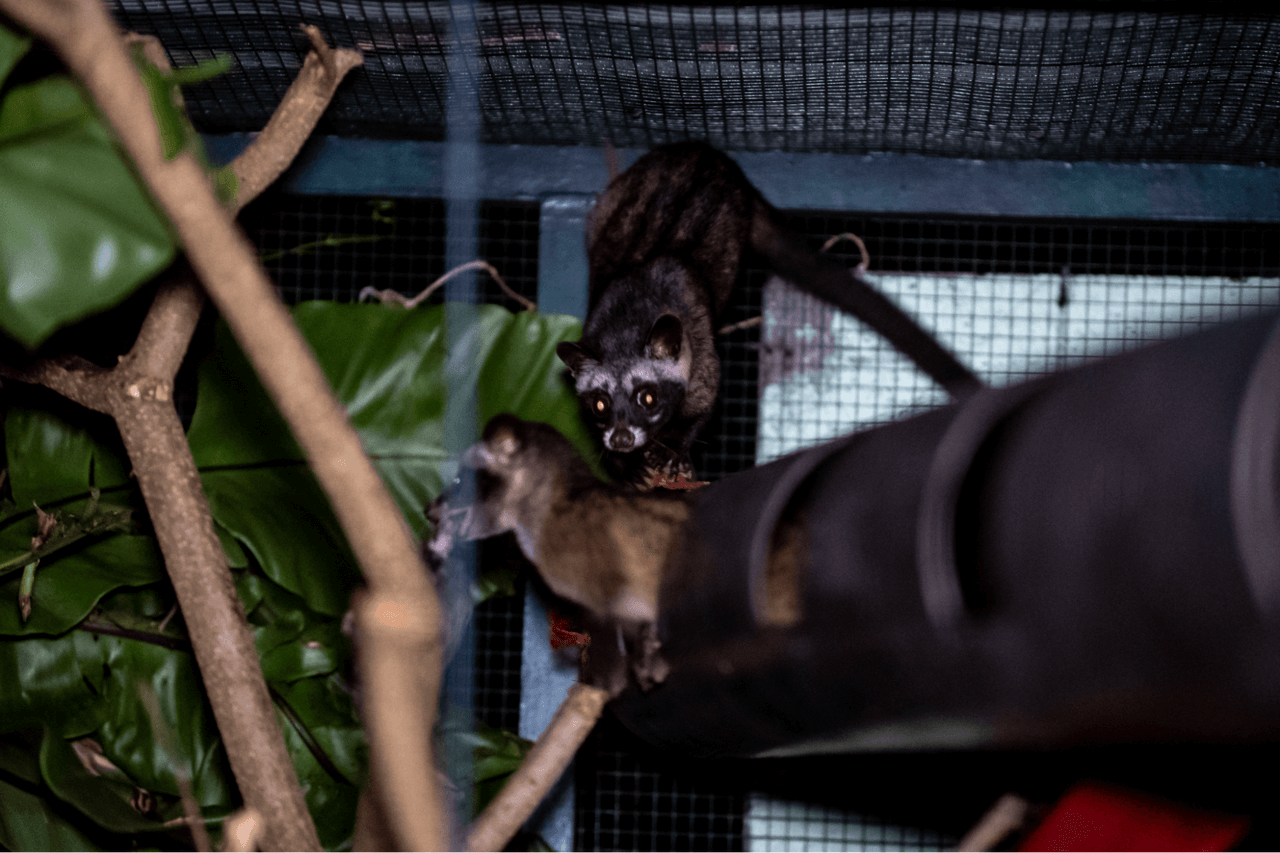

We start with dinnertime for the animals, who need to be seen to before we get on the road. ACRES’ rehabilitation centre houses a variety of native species (mostly birds, as well as a few iguanas, squirrels, and civet cats), which are brought in by the rescue team and nursed back to health.

They also house non-native species like exotic tortoises, most of which have been illegally imported as pets and abandoned. While ACRES usually tries to rehome them with zoos or conservation groups back in their native countries, COVID-19 has made this even more difficult.

Syaz, the staff member accompanying Kalai on tonight’s shift, shows Bing and I around the cages. They’re set up with plants and structures that mimic the animals’ natural environments in a bid to ‘re-train’ them for release. Unfortunately, a squirrel leaps out to greet us as soon as we approach with food.

“It shouldn’t be doing that,” she sighs.

She talks about how well-meaning callers sometimes keep injured baby animals they find for a few days. During this time, the animals can begin to ‘imprint’, or bond, with humans, and that’s when the trouble starts. A squirrel which can’t find its own food will never survive back in the wild.

ADVERTISEMENT

“People have good intentions, but they don’t like being told not to play the hero,” she says. “I mean, it’s great that people want to help… but sometimes, it’s better if they don’t.”

1945: Humans are the worst.

Our first rescue for the night is— you guessed it— another python, this one somewhere in Bukit Timah. Here, I encounter my first truly obnoxious caller, a woman who issues a running commentary from the gate of her GCB while Syaz and Kalai pull the python (a relatively small, 1-metre-long chap) out of a bush.

“Please don’t come closer, I’m not wearing a mask and I don’t want to catch COVID,” she shouts from a distance. Bing and I exchange A Look.

She continues to pelt the team with questions. Why did you take so long to come? Is it a big snake? Eeeeyer, are there more? Her two domestic workers hover in the background, watching nervously. The whole exchange would read like parody if it wasn’t, alas, real.

2200: The pigeon problem

After dinner — a mountainous thali set and hot chai in Little India — we head off to Buangkok to pick up another pigeon.

At this point, I should mention that I really don’t like pigeons. I try to live and let live, but I also think they’re rats with wings. Nonetheless, they’re a fascinating case study in how Singapore deals with wildlife it deems a nuisance.

According to Laurie, the volunteer from the first shift, ACRES frequently gets calls about pigeons. Some of these are indirect casualties of other forms of pest control, like when they get caught in glue traps left for insects. The bugs get stuck in the glue, the birds notice the buffet spread, start feasting, and get caught in the glue themselves. Often, however, the pigeons they get called for are survivors of culling attempts.

In dealing with pigeon complaints, agencies like the NEA, AVA, and town councils employ a mix of responses. Some of these are design deterrents (spikes and nets) or education-based (anti-bird feeding campaigns), but they also rely on pest-control companies to manage numbers. These companies generally use poisoned bait, which can take out as many as 20 to 30 birds in one go, if not more.

The problem, according to Kalai, is that poisoning the birds is both ineffective and inhumane. First, it doesn’t tackle the root source of the problem: feeding.

A recent NParks-funded study of local feral pigeons found that food availability is the primary driver of bird population growth. The Wildlife Act, which came into force last June, specifies large fines for bird feeding, but it’s unclear how often they are handed out, or how effective a deterrent they are. “It’s an ongoing war between feeding and culling,” he said.

Second, poisoning is an indiscriminate method which can take out other wildlife. Other birds and animals might consume it, while predatory birds which eat pigeons can also become secondary victims, like the white-bellied sea eagle which recently collapsed outside the Supreme Court (and was rescued by ACRES).

The thing is, there doesn’t seem to be an easy resolution to the problem. While I take Kalai’s point about the cruelty and inefficacy of poisoning, the parties involved are all approaching the same issue from different angles.

ACRES, as an animal protection charity, takes a welfare-driven approach. I’m sure town councils don’t want to see eagles inadvertently poisoned, but their priority is to keep residents happy and estates clean. As long as culling gets a visible reduction in pigeon numbers, it looks like something’s been done about the problem.

The real long-term solution—reducing feeding—involves changing human behaviour. And as Kalai, Laurie, and Syaz can all attest to, people can be far harder to teach than animals.

2300: Bats and bearded dragons

Our next stop is in Dover for a mouse-eared bat. Over the drive there, I ask Kalai and Syaz about their weirdest calls.

There is the West Coast Flute Lady, a Pied Piper-sort of figure, but for pigeons rather than rats. There is the Man Who Claimed To See A Two-Headed Snake In His Car. Then there is the Curious Case of the High-Rise Cobra, when Kalai got called in for a spitting cobra under a wardrobe in a 13th-floor HDB flat.

Meanwhile, Syaz talks about acclimatising to the job. As the newest member of ACRES’ full-time team, it’s been a steep learning curve. She jokes about the time she went down a manhole for a python and came up covered in python pee, because pythons, like many animals, urinate when stressed. (FYI: They can also throw up.)

When we finally get to Dover, Syaz goes in to collect the bat, while Kalai takes a call. Over the last few hours, the hotline has been receiving repeated calls from a man claiming to have found two Bearded Dragons. Kalai, however, suspects they’re actually illegal pets, and the caller is trying to get rid of them.

Bing and I go with Syaz to retrieve the bat, which is weak and cold after getting soaked in the rain. The teenagers who found it also fed it milk, which, while kindly meant, was not a great idea. It’s not very responsive, but Syaz feeds it with a syringe and sets it on a heated pad for the drive back. All we can do now is hope for the best.

0030: Back to ACRES for the night

The calls are slowing by 11:30PM, so after getting the bat, we decide to head back to ACRES HQ—an unusually early night by the team’s standards. On a bad shift, they can be out till 3:00 or 4:00AM, though Kalai jokes we might still get a call for a pangolin.

We pull up to find several more birds in the drop-off box outside the gate. Callers sometimes bring in birds which the team can’t get to, and tonight, there are starlings, a bul-bul, a baby myna, and another pigeon.

I’ve never been terribly fond of birds. I don’t expect this to change, even after this assignment. I will still give pigeons a wide berth and glare at the mynas eyeing my prata at the coffee shop. But watching Kalai and Syaz get all the animals comfortable for the night—giving the poisoned pigeon charcoal, settling the fledglings in the incubator units—is nothing short of deeply moving.

The bat we picked up in Dover is just one of thousands, nothing special in the slightest. If the teenagers hadn’t found it and it died during the night, it wouldn’t have been missed. But here is Kalai all the same, tenderly checking it for injuries and hand-feeding it with a syringe at 1:00AM, because it is a life, and to ACRES, all lives deserve compassion, even the forgettable ones. Especially the forgettable ones. It is a privilege to watch such small things treated with such deep love.

The heating pad has worked. The bat’s revived enough that Kalai thinks they’ll be able to release it in the morning.

0830: On the road again

I blink awake in my bunk just after 6:00AM. At first, I worry that I’ve slept through calls, but it turns out to have been an unusually peaceful night. I can’t decide if I’m grateful for the extra sleep or disappointed that we didn’t get to see a pangolin.

In the bed opposite, Syaz is already scrolling through the call logs for the morning, her face lit by the blue glow of the phone screen.

By 7:00AM, everyone is up for the birds’ first feed of the day. The incubators are checked out—two starlings died during the night—and the animals get breakfast. A call comes in for a paradise tree snake in Whitley, and we decide to go make one last rescue.

We arrive at the site, a black-and-white colonial bungalow, to find the caller family awaiting our arrival. It takes me a while to spot the snake. It’s small, and despite its bright colours, so perfectly lined up against a window frame as to be virtually invisible. The family probably only noticed it while trying to open the window.

Despite their initial nervousness, the family starts to relax as Kalai and Syaz deliver their nature lesson. Paradise tree snakes are common in Singapore and not dangerous, other than to the small lizards they hunt.

From the other side of the window, the teenage son reaches out to stroke the snake. Its bright red-and-green skin glimmers in the morning sun.

“Cool,” he says.

Having been reassured that the snake is harmless, the family consents to have it released in the back garden. The mother, who’d been the most anxious initially, is now peppering Syaz and Kalai with enthusiastic questions. What’s considered a big snake? How common are they? She seems surprised, albeit not alarmed, to hear that there are probably several more in the surrounding foliage, and allows us to saw off part of a fallen palm to bring back for the civet cats.

As we attempt to stuff the tree into the van, a cry overhead makes everyone look up. “Hornbills,” says Kalai, pointing to a pair that have landed in a nearby tree. The family watches, delighted, while the birds go about their business.

I can’t imagine what they must think, having to put up with us. After all, in their eyes, we’re probably the foreign species, the strange, lumbering idiots on this planet full of creatures big and small.

Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co. If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook and Telegram.