A baby hatch at Petaling Jaya (Top image: OrphanCare)

It was the year 2019, and a regular morning for most. In the small town of Kota Belud at Kampung Pompod, Sabah, two individuals—a woman who works as a clerk and her mother—would find their lives upended.

A newborn baby was left at the doorstep of their house.

ADVERTISEMENT

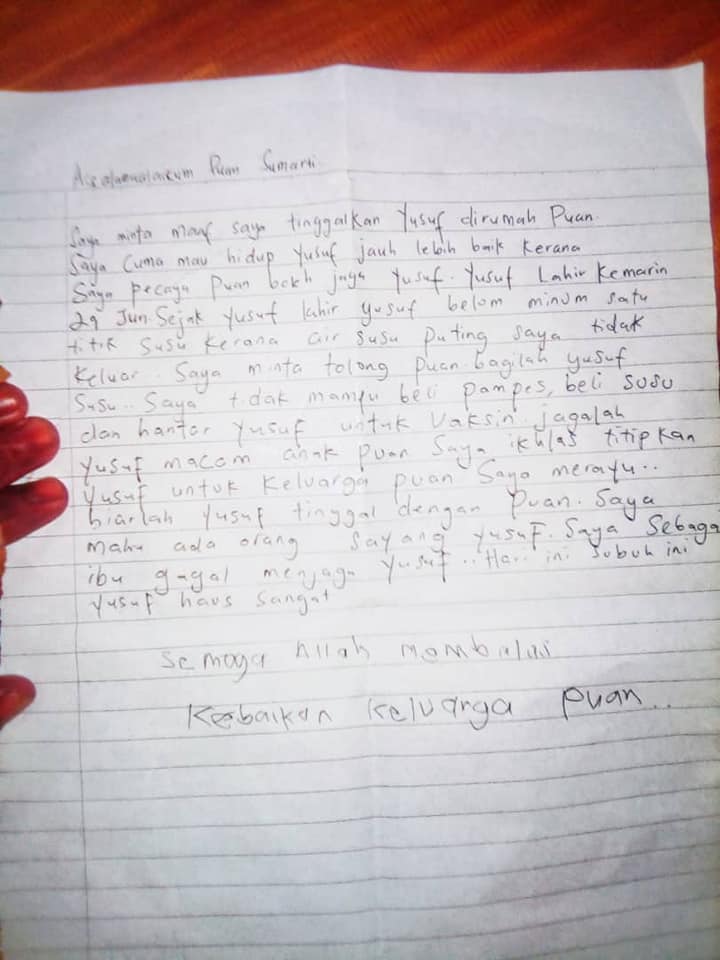

“Forgive me for leaving Yusuf at your door,” the opening stanza of an accompanying letter reads, summarising what baby Yusuf has endured so far in his short, brief life.

“Please allow Yusuf to stay with you. I want someone to love him. As a mother, I have failed.”

According to the letter, the child hasn’t had a drop of milk since his birth on June 29—his mother could neither produce any breast milk nor could she afford formula.

“May Allah repay the kindness of you and your family,” the letter concluded.

Yusuf was only a day old when his birth mother abandoned him. He is one of the lucky few to survive being abandoned. Six out of ten babies in Malaysia are not so fortunate—here, one baby is dumped every three days.

Baby Hatches: Useful or Not?

While a comprehensive sex education curriculum can aid in preventing unwanted pregnancies, a more immediate, pro-life solution to Malaysia’s baby dumping problem is the baby hatch.

ADVERTISEMENT

According to OrphanCare, an NGO advocating for deinstitutionalization and the welfare of pregnant women in Malaysia, the baby hatch is a concept that dates back to the Middle Ages. At the time, it was known as the foundling wheel—a cylinder set upright in the outside wall of a building that looks like a revolving door.

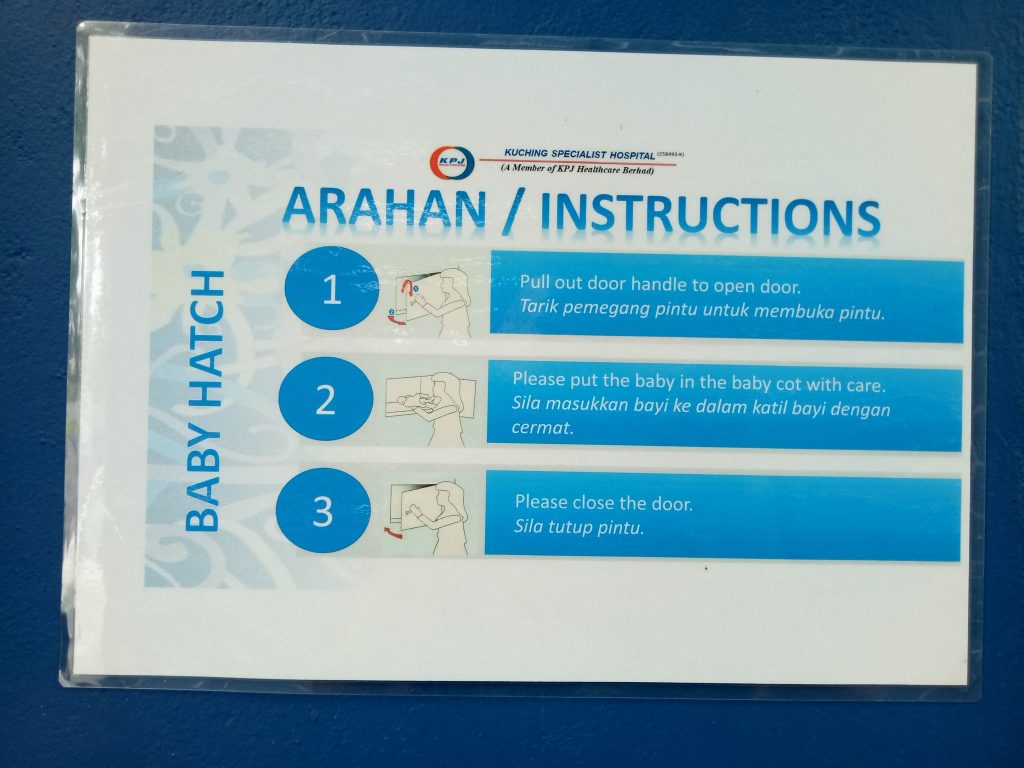

Today, baby hatches can usually be accessed from outside a building so people can place their babies in the available cribs without being identified.

The design and construction of baby hatches have since evolved from medieval times. Still, their objective remains the same—to save innocent lives from being abandoned in unsafe places. Or worse, left to die.

In Malaysia, OrphanCare launched the baby hatch initiative in 2010 to curb the burgeoning baby dumping problem.

Still, despite their joint efforts, over a thousand babies have been discarded all over Malaysia, often in public areas ranging from public toilets to motorcycle baskets.

Presently, OrphanCare has three hatches that they independently maintain in Petaling Jaya, Johor Bahru, and Sungai Petani in Kedah. They also own a handful scattered across the nation in collaboration with KPJ Healthcare Berhad, a private Malaysian hospital.

One Baby Hatch Down

Sarawak, where I stay, opened a baby hatch at KPJ Kuching in 2017. But it has since closed down.

“We closed the baby hatch after moving to the new building,” the receptionist shared when I asked why it was closed down. KPJ Kuching Hospital moved from the shophouses at Jalan Setia Raja to a new building at Jalan Stutong. It started operations in the first quarter of 2020.

The hospital tells me there are no plans to reopen the baby hatch soon. “There isn’t a suitable location for it at the moment,” a representative from the hospital’s marketing team informs me.

When I ask why wasn’t the baby hatch included in the blueprint for the new hospital, I was told to contact their general manager for answers.

At the time of publishing, I have yet to hear back from anyone from KPJ Kuching about future plans for a baby hatch.

Stumped, I turned to 62-year-old Angie Garet, the president of Sarawak Women For Women Society (SWWS), an organization that supports women and children in distress. Perhaps she might have a solution to the problem of baby dumping in Sarawak.

ADVERTISEMENT

Just this year alone, a total of four baby dumping cases were recorded in Sarawak. The latest happened last month in September.

“SWWS has no plan to provide shelter to the unwed and vulnerable as we don’t have the resources to do so,” Angie tells me over text. “But SWWS are there to listen through our helpline to explore options with the woman and share information on services available in Sarawak.”

However, Angie is on the fence about baby hatches, stating that most mothers intending to hide their pregnancies often give birth in secret and will not have readily available transport to go anywhere. Let alone a baby hatch.

“What these young girls need more now is empathy so that they can get the support they need much earlier,” Angie adds.

In some ways, Angie was right. Baby hatches aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution—that would be education.

Ignorance Breeds Babies

“My mother never even taught me about periods,” Daisy* tells me when I ask if her parents gave her the talk about the birds and the bees. We’re chatting at a cafe near her office—seated in a corner so that nobody can hear our conversation.

Gentle and soft-spoken, it’s hard to believe that Daisy has had two abortions. Her first was when she was 18. Daisy is now 30 and married, with plans to start a family of her own.

“I was too young to be a mother then,” she admits before I can ask the reason for not keeping the baby. Daisy casually mentions using birth control, such as condoms and the morning-after pill. But she admits that, sometimes, “accidents happen.”

She shrugged when asked how she plans to teach her children about reproduction. “Everything I knew came from my boyfriends.”

“How about school? Did school teach you anything?” I prodded.

“I can’t recall. There must have been a class about it. But I can’t remember a single thing. We should have a class every year, and reproductive classes should start from primary instead of waiting till secondary.”

Start Them Younger

Daisy isn’t the only one who found Malaysia’s sexual health education lacking. I called friends who went to Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan—public schools that are known locally as SMK—to ask about their experiences.

It soon became apparent that a Malaysian student’s sex education boils down to one biology class in Form Three (14 to 15-year-olds) about reproduction.

Even though PEERS, a reproductive and social health curriculum, was implemented in secondary schools in 1989, it doesn’t seem to have made an impact.

“Apa itu seks ed?”

“What is sex ed?” is a typical response when I ask school administrators whether sex ed is being taught in their respective public secondary schools. I am referred to the school counsellor when I mention consent, body image, relationships, and STDs.

I contact the Ministry of Education to ask if there are any plans to update their curriculum to include comprehensive sex education. All I got in return were automated replies and unanswered calls.

“I think children must be able to identify their anatomy from an early age,” explains Grace Wong, 35, the principal of Green Eduland Kindergarten. In her school, five and six-year-olds are taught body awareness and sexual consent.

Grace believes that teaching kids about their body parts and what sexual consent is can help keep them safe. “At the same time, it also teaches them what is appropriate behaviour,” Grace adds.

Grace was formerly an early childhood lecturer at Malaysian college Segi before she moved on to running her own kindergarten. She is also a part of Little Bean, a community-led initiative of mothers in Kuching. They use storytelling to drive home lessons about morals and, more recently, sex.

Today, the group’s services are in high demand. There’s even a waiting list of Chinese primary schools that have invited Little Bean to conduct sex ed workshops at their institutions.

While some might opine that sex ed in preschool might seem a tad too premature, there are, in fact, many circumstances during school hours where an understanding of boundaries are essential.

“Sometimes they may touch each other at sensitive areas or slap each other’s butts during roughhousing or play,” Grace elaborates. “That’s when I know it’s time for a refresher class about personal space.”

In Malaysia, Sex-ed Does Not Start In School

According to a study published in the Journal of Advanced Research in Social and Behavioural Sciences, sex-ed in Malaysia relied primarily on promoting abstinence.

Many are under the impression that they can delay their children from being sexually active simply by not talking about it. In conservative Malaysia, nobody wants to believe that their teenager is sexually active.

The problem is further exacerbated with the introduction of a sex ed module in government schools called, ‘Modul Pekerti‘ (‘Good Character Module’).

The module reinforces the idea that sex before marriage is immoral and focuses on preventing students from engaging in any sexual activity.

‘Modul Pekerti‘ is the brainchild of The National Population and Family Development Board (LPPKN). The LPKKN is a government organisation that focuses on enhancing harmonious living in Malaysian families by instilling family values, offering family planning, and teaching financial literacy.

The head of the Fertility Division in LPPKN, Dr Hamizah, reiterated to the Malay Mail, “The module is about preventing sex. We do talk about safe sex, but the demonstration of how to wear a condom, for example, is not allowed in schools.”

The Heavy Price of Withholding Information

The rising numbers of teen pregnancy and baby dumping in Malaysia is a clear indicator that selling the idea that sex is shameful and instilling abstinence as a prevention method for teen pregnancy is just not working.

In 2019, Malaysiakini published that over 18,000 teenage girls in Malaysia get pregnant every year. Many more are likely to go unreported.

The fear of being stigmatized as an unwed mother and the contributing ignorance of safe sex practices have led to devastating repercussions—unsafe abortions.

A study titled ‘Issues of safe abortions in Malaysia: Reproductive Rights and Choice’ prepared by the United Nations Fund for Population Activities found that unsafe abortion in Malaysia accounts for 1 in 5 maternal deaths over the period of 1995 to 2006.

The paper also went on to illustrate the lack of available data on abortions due to underreporting in Malaysia. Women have been driven to seek abortions from underground practices or forced to discard their babies in secret.

Many Malaysians mistakenly think that abortion is illegal. They are unaware that Malaysia’s Penal Code was amended in 1989 to include a clause that allows registered medical practitioners to perform abortions.

The caveat is that abortion is necessary to keep the mother mentally and physically healthy.

And while religious faculties like ProLife or NGOs like SWWS offer support and counselling for unwed mothers, they do not offer abortion as an option.

Even doctors who provide early pregnancy termination rarely publicize their services due to the stigma associated with abortion.

Enter the Brave Doctors

Still, that’s not to say that there are no doctors in Malaysia that offer this service. Dr S.P. Choong is one such practitioner. He also co-founded Reproductive Rights Advocacy Alliance Malaysia (RRAAM) and has been vocal about making abortion an openly available option for pregnant women.

The doctor started fighting against the stigma some forty years ago. He began by volunteering in family planning and petitioned for abortions to be readily available in Malaysia.

When that didn’t work out, he resigned from his position as the head of the Federation of Family Planning Associations Malaysia. He set up RRAAM to promote sex education and contraception.

To build a network of pro-choice doctors across the nation, RRAAM sent a representative around the country to interview 80 doctors that offered pregnancy termination. “only about 20 agreed to come openly and join our network of doctors,” says Dr Choong.

Dr Choong soon learned that there’s an unshakeable stigma surrounding abortion which makes public identification of doctors who perform this service tenuous.

Over text, Dr Choong tells me he believes that the fault of baby dumping primarily lies with Malaysian society. We simply don’t provide adequate sex education in schools—nor do we give women the confidence to refuse sexual advances without consent.

“And when an unwanted pregnancy occurs, there is very little public information on abortion services,” he adds. “We must ensure that people who need an abortion will get one. And not only that, but that they will get one safely and at a reasonable cost.”

Innocence Offers No Protection

According to OrphanCare, approximately half of the pregnant women they receive in their care are victims of rape.

“Sometimes, they don’t even know the rape happened,” 51-year-old Puan Riza, OrphanCare’s Advocacy & Communications Officer, shares. Puan Riza joined OrphanCare in 2019 to raise awareness about the organization to reach at-risk individuals that need their help.

“I had a 19-year-old girl come in who said she didn’t know how she got pregnant, but through counselling, it was revealed that a cousin had forced himself onto her while she was sleeping.”

The victim had woken up with her cousin on top of her forcing himself on the youth. She said that “it hurts down there”, but her cousin told her to keep it to herself. When her stomach grew, she was brought to bomohs (witch doctors), as it was believed her growing stomach was the work of black magic.

When it became apparent that pregnancy was more likely, her family reached out to OrphanCare.

“She was so innocent,” Puan Riza adds. “She kept repeating, ‘but I’m not married yet’ as if being married was a prerequisite for getting pregnant.”

The Price of Rebellion

The victim’s naivete is not unsurprising. For Muslims, zina—any sexual relations outside of traditional marriage—is a grave sin leaden with judgment.

To make matters worse, in the community, parents and elders brush the topic of reproduction aside with a simple “you’ll know when you’re married”. This would have reinforced the idea that babies only came after marriage, not after unprotected sexual intercourse.

Puan Riza shared that young Muslim girls in Malaysia are disproportionately vulnerable to risks such as sexual abuse, rape, or teen pregnancy. This, she believes, is due to poverty and lack of education.

The same sentiments were expressed when I spoke to Maisarah, a counsellor at Taman Seri Puteri Kuching, a facility for troubled teenage girls. She, too, noticed that many pregnant teenagers placed under their care are Muslim.

“Islam is a very strict religion,” Maisarah offers when I ask why so many of the teenagers under their care are Muslims. “The Malay community lives with so many taboos, and there are so many things we are forbidden from doing.”

“So when children reach the age of adolescence, their curiosity peaks and they start to rebel against the rules and restrictions that govern them.”

She also highlights how Malaysian culture is not receptive to developing a healthy mindset towards sex. “The issue of sex ed seems small, but it is essential in dealing with preventing teen pregnancy and baby dumping.”

Poor sex education, the lack of abortion awareness, culture, and faith—these are the factors that contribute to Malaysia’s baby dumping dilemma. The solution, while obvious, feels Sisyphean given the sheer number of government agencies that need to work hand-in-hand to make baby dumping a thing of the past.

But until that happens, the most approachable solution, at least for me, is to at least provide baby hatches around the country.

Aside from its function of ensuring unwanted newborns like baby Yusuf live to see another day, baby hatches are an uncomfortable visual reminder that Malaysia has a baby dumping problem that no one seems able to solve.

And if that is what it takes to find a viable and practical solution to this problem, perhaps it’s time we get comfortable with uncomfortable truths.