All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media unless otherwise stated.

“I agreed to your interview because you called me an ‘elder statesman’ in your email.” It’s the first thing Najip Ali says to me when we meet.

“People don’t usually call me an ‘elder’,” he laughs.

ADVERTISEMENT

Najip is irrefutably an elder, but in a good way. The 57-year-old wields an enthusiasm for life that makes millennials see him as a peer, surprising for someone who’s been forging a road for Singapore’s cultural and entertainment scene for over 40 years.

In the local entertainment industry, we are not short of flashes in the pan. When I consume content these days, I often find myself thinking, ‘Wow, that entertainer is destined for stardom’. Only for said entertainer to fade into obscurity as fast as they appear.

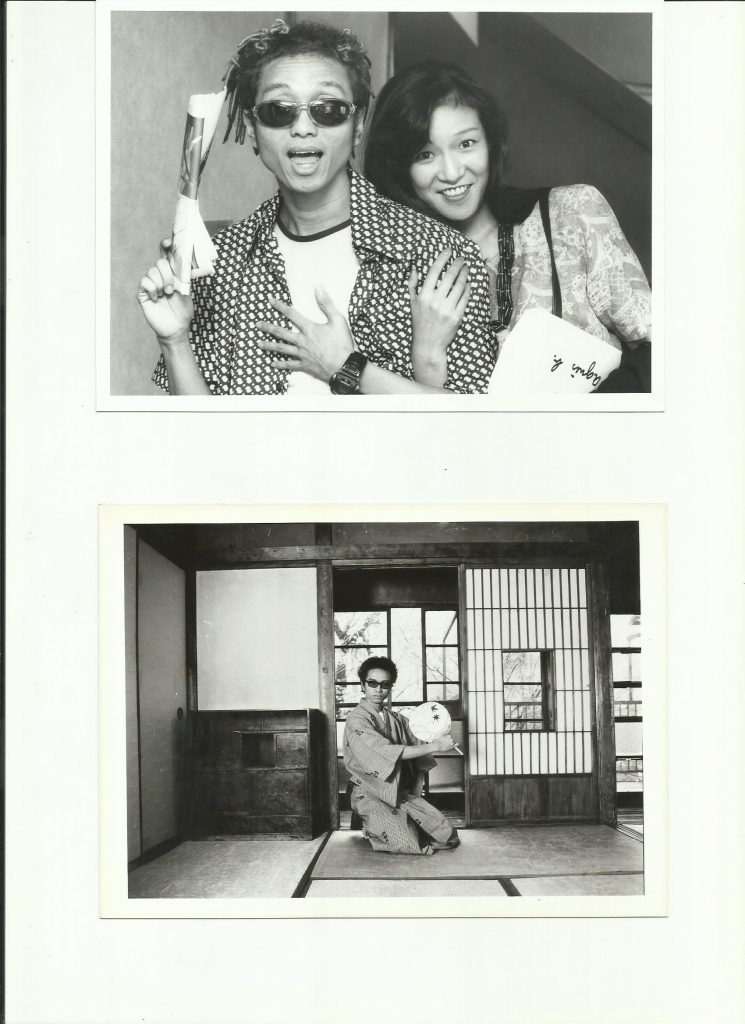

And then there’s Najip Ali, who has been adored since the early ‘90s and remains a pillar of the Malay entertainment scene. Ever since he was scouted from the dancefloors of old Zouk to co-host the regional star-search television programme Asia Bagus, Najip has never stopped championing and nurturing young talents.

Unbeknownst to many, however, Najip is the secret godfather behind Singapore’s thriving arts and culture underground. For decades, this man has been a silently influential force of nature, tirelessly supporting emerging musicians, artists, and creatives. His contributions have been pushing forward Singapore’s brand of avant-garde expressions that might otherwise have been stifled in the mainstream.

As the impact of his efforts becomes more evident today, it’s high time for Singaporeans to acknowledge and celebrate the pivotal role Najip has played in shaping the city’s cultural landscape.

They say don’t meet your heroes. But I’m glad I did.

The Man With The Microphone

A core memory from my childhood is watching an inexhaustibly animated and deafeningly dressed man host an eclectic variety show on Saturday afternoons.

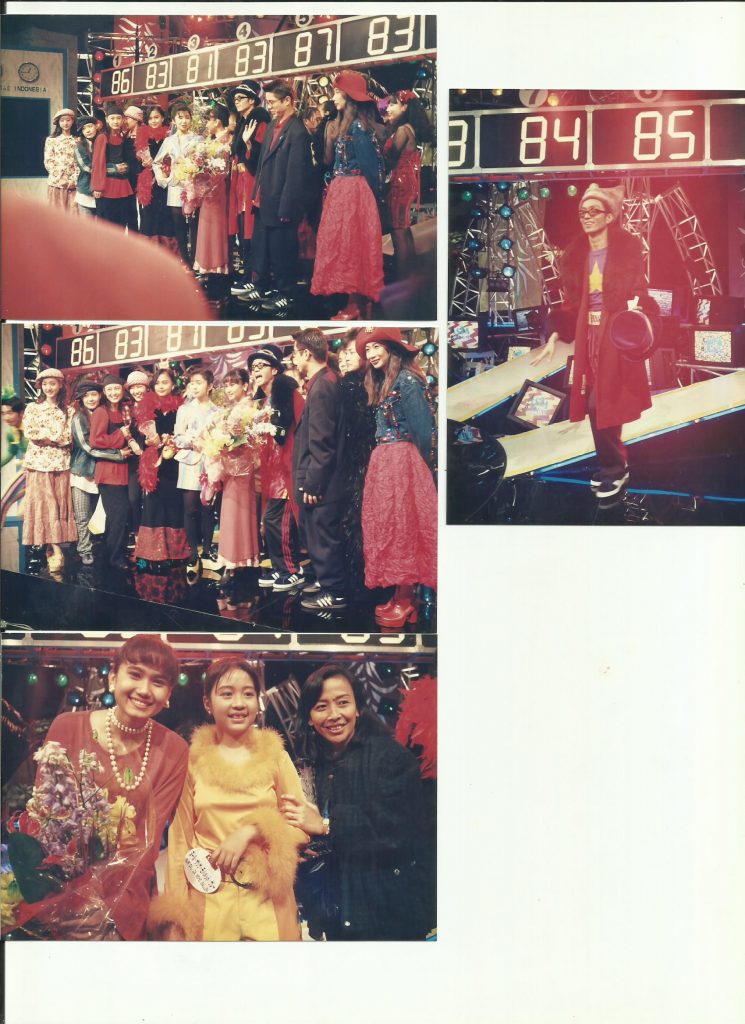

That variety show was Asia Bagus, which ran from 1992 to 2000. It was a talent competition that spotlighted a mishmash of musical artists from across Asia, from Indonesian ballad singers to Malay rappers.

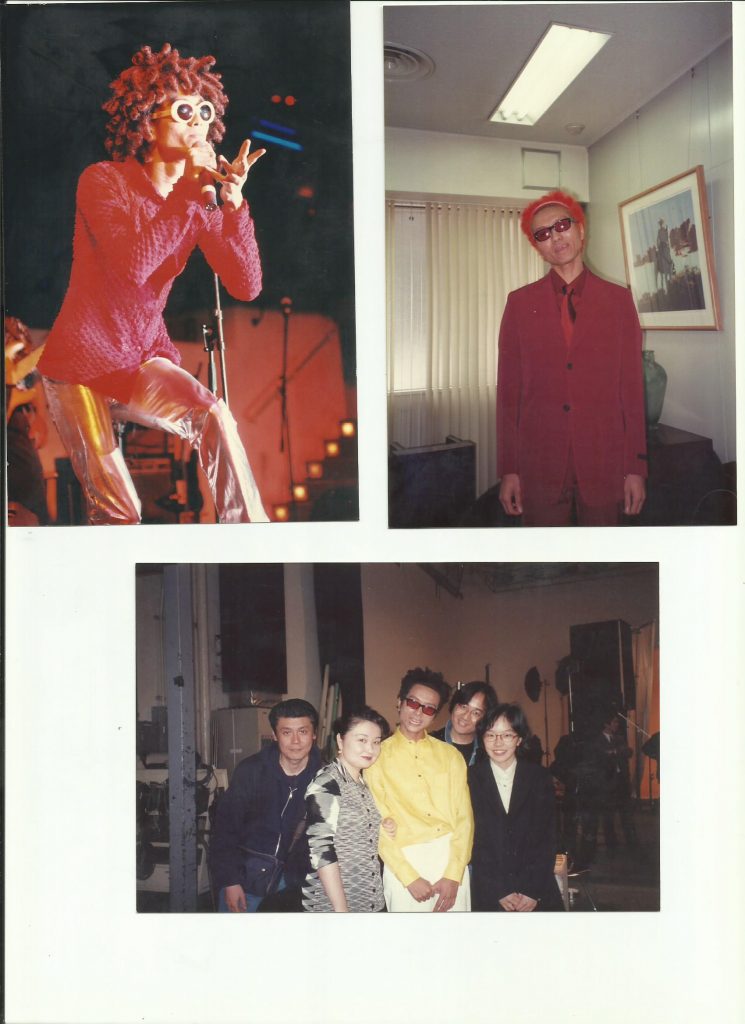

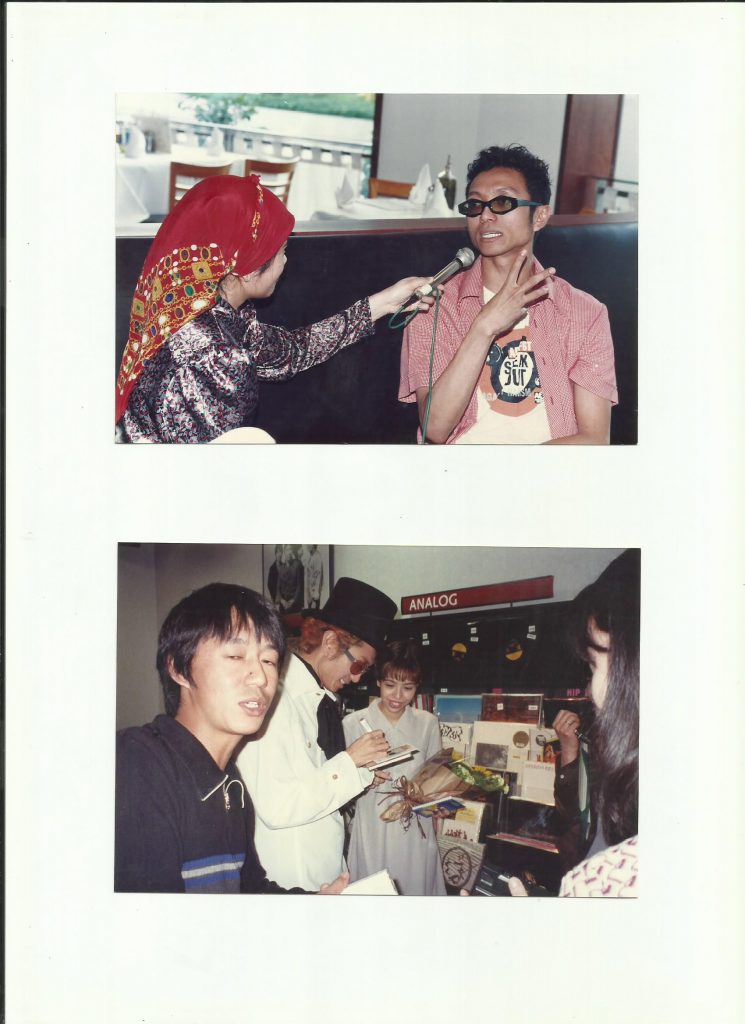

If the confusing diversity of these genres didn’t alienate viewers, the greenness of these non-professional musicians did. However, viewers couldn’t look away from a presenter named Najip Ali, who would flail and dance like an inflatable tube man while introducing the musical acts.

Asia Bagus was broadcast across Asia for almost a decade, which made Najip an unmistakable regional star.

It was impossible to look away as Najip mustered every ounce of his lifeforce to get audiences excited about artists they didn’t know. It was only after I grew up and started hosting live shows that I came to understand the tenet of live entertainment Najip was channelling every fibre of his being into: You must look excited so your audience will feel excited too.

I couldn’t put my finger on where Najip got his fashion cues from. Jamiroquai? Teriyaki Boyz? But Najip was rocking these oversized, head-turning outfits a decade before these bands even came into prominence.

ADVERTISEMENT

During our tête-à-tête—interspersed with his signature disarming belly laughs—Najip reveals to me that his stylistic inspirations came from Deee-Lite, a pop band from New York City that is best known for its international chart-topping hit ‘Groove Is in the Heart’.

If you know ‘Groove Is in the Heart’, congratulations! You’re probably collecting your CPF soon.

I’ve also wondered which comedian Najip based his vivacious and unabashed hosting style off. I run my top guesses by Najip: Perhaps it was that era’s most popular comedians like Eddie Murphy or Benny Hill? He corrects me that it was, in fact, a style he improvised off outrageous Japanese TV programming.

“I learned from Japanese television the importance of energy. I couldn’t understand much of what these hosts were saying, but the vibe was killer. These hosts would appear naked in one scene, and get pushed into a well in the next scene’s prank. In Japan, entertainment is entertainment, where there are no etiquette rules.”

Tokyo Calling

“Asia Bagus was actually Japan’s soft power diplomacy. It was backed by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs because Southeast Asia was on the rise,” Najip explains when I ask him about how it all started.

“Japan always wants to be a part of growth. Japan wanted to be part of this Asian renaissance, if you will, and Asia Bagus definitely captured the imagination of people across Asia.”

Among the many things people might not know: Najip reveals that he was plucked from obscurity—out of all places, while he was partying in Zouk.

Television execs noticed this cool kid in the popular nightclub who did not look Chinese, Indian, or Malay but “more like someone from the kawaii subculture”. They asked him to host this upcoming TV show.

A massive fan of Japanese culture who was still cutting his teeth as a host, Najip felt like his prayers to be able to visit Japan were finally answered. He accepted the offer.

Language, however, was an initial barrier. Najip did not understand Japanese, and in 1992 on Asia Bagus, he did not understand his co-host Tomoko Kadowaki either.

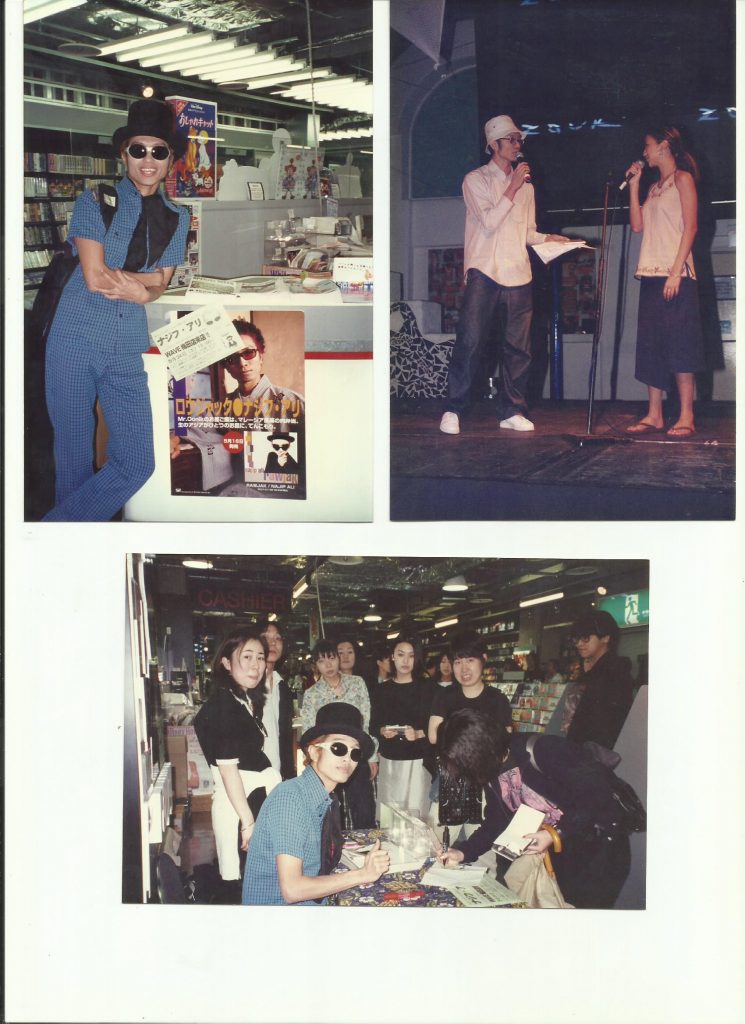

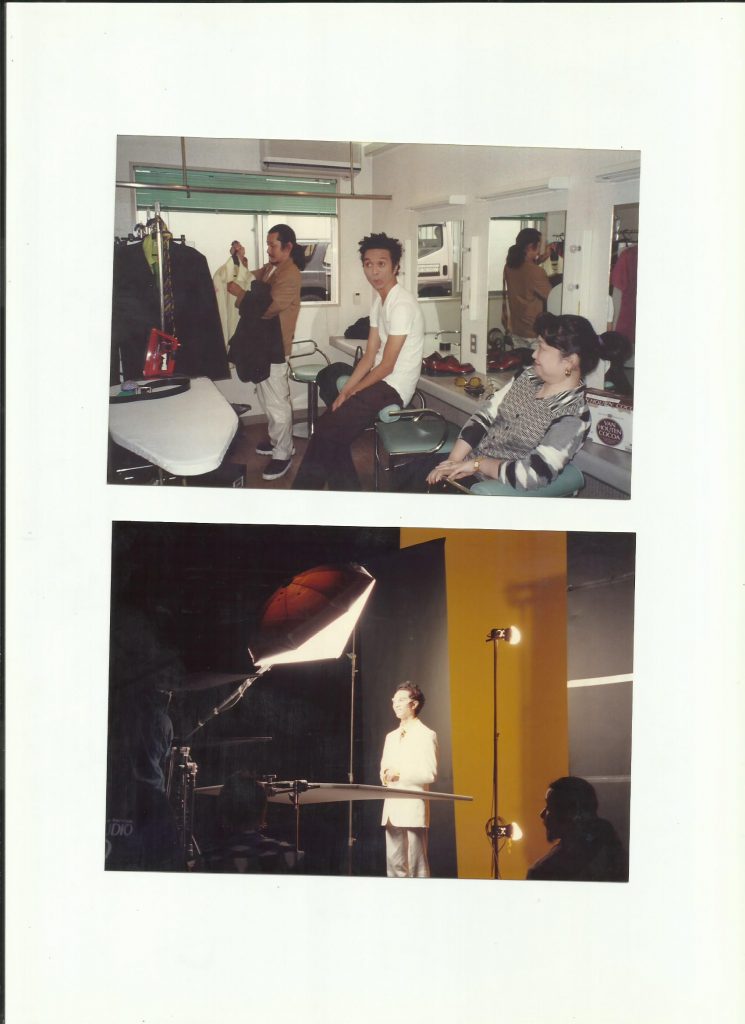

“Asia Bagus didn’t have a script and I had the autonomy to dress how I liked! I was insecure about my face, which is why I opted for the Deee-Lite-inspired big glasses and big hats. I played the fool, Tomoko would scold me on camera and viewers really liked that dynamic. In fact, I became very popular because people took pity on me—so popular that [Japanese entertainment label] Pony Canyon commissioned me to release two music albums.”

Asia Bagus was a watershed moment for talent competitions in Southeast Asia. It launched the careers of regional household names in music, including Indonesia’s Krisdayanti, Malaysia’s Amy Mastura and Singapore’s own Sheikh Haikel.

It marked a transition during which the entertainment scene grew from holding local singing competitions like Talentime and Rolling Good Times to putting on international spectacles. In fact, when Asia Bagus ended its run in the early 2000s, it left a vacuum that would later be filled by Singapore Idol and Asian Idol.

One could even argue that Asia Bagus was a foreshadowing of the reality talent show craze, which has since spawned international editions around the world and millions of viral reels.

Might a TV show as eclectic as Asia Bagus work in this age of segmented programming?

“It might work, but it’s got a lot to do with money. Asia Bagus was backed by big sponsors like Sharp, Sony and Panasonic, and we needed that backing to pay for things like contestants’ flights. I really enjoyed how Asia Bagus showcased Asia’s colourful talents, put on display by Asians of various skin colours.”

First Love

Among the many art forms that Najip has championed during his storied career, dance choreography was his first love.

“As a child, I didn’t have any inkling to sign up for dance classes. My father only sent me to religious classes,” recounts Najip.

He was not privy to the breadth and depth of dance and the performing arts until he was drafted into the Singapore Armed Forces Music and Drama Company (MDC).

“While other NSFs were carrying rifles and going outfield, here I was singing, dancing, and doing what I loved—can you imagine that?”

Recalling this memory causes Najip to let out his iconic howling laugh, a laugh that has reverberated from Singaporean television sets since the early ‘90s.

“These are some of my fondest memories of my life. Besides exposing me to the vast possibilities of the entertainment world, the MDC is where I learned more about dance, and I became increasingly attracted to the form of dance.”

When Najip completed his National Service in 1984, he went on to host talent shows and choreograph more dance routines. His penchant for dance would land him a Fellowship Award from the British Council to study dance in London and open even more doors for him. Soon, he would find himself working alongside future theatre legends like Ong Keng Sen, Michael Chiang, and Dick Lee to put on the musical Beauty World.

“The height of my career as a choreographer was choreographing Beauty World, and that opened more doors, helping me burst into a whole lot of other musicals.”

The Mailman Of Culture

Throughout his time training in London and working as a producer for Fuji Television in Japan, Najip had been bringing music magazines, CDs, and vinyl records back with him whenever he returned home to Singapore.

“I love magazines. My main reading material when I was growing up was magazines like Blitz, GQ, Mixmag and The Face. Back when the world wasn’t this connected through the Internet, I had the privilege of seeing the world, so I asked myself what changes I could make in my local scene. Music wasn’t my main thing, but I came up with the idea of starting a thinking culture in the music scene.”

Najip cites his role model as promoter Malcolm McLaren, who was a fervent proponent of future cultural icons like Vivienne Westwood and the Sex Pistols.

“I like how people like Malcolm could move a group of people to do something. And these people whom you inspire will, in turn, keep you doing it.”

The globetrotter hosted small parties in his garage along Portsdown Road—a garage that had no car but was overflowing with music memorabilia.

“The friends I invited over would open a magazine and go, ‘What the hell is that?’ They became very interested and very curious. ‘What is that party about?’ ‘What is a rave?’ This sparked their desire to find out more, and I think desire in an artist is very important.”

Among the wide-eyed, aspiring artists who benefitted from Najip’s generosity is veteran DJ Kiat. Today, Kiat is known as one of South East Asia’s pioneers of the drum & bass sound and has played in gigs across the world.

“Najip brought music and magazines back from the cultural explosions in Japan and the UK for us,” says Kiat. “It was the freshest music we could consume, and it influenced me hugely.”

Kiat highlights that in the early ‘90s, Singapore had no places for listening to new and current music. To Kiat, Saturdays in Najip’s house felt like listening sessions in a little library of intriguing new sounds.

“I’m forever grateful, and it made me want to pay it forward. I must add that Najip also gave me the chance to play my first gig, back when I had no prior experience.”

Rapper, host, actor, and restaurant entrepreneur Sheikh Haikel also shares that Najip played a big part in every aspect of his career.

“Back then, SBC (now known as Mediacorp) paid people $10 to be the audience for TV shows they filmed, so my friend Ashidiq Ghazali and I would go there to be audience members of Asia Bagus and make some money,” says Sheikh.

Local rap duo Construction Site comprised Ashidiq and Sheikh, who rose to prominence by performing on Asia Bagus and winning its second season in 1993.

“Asia Bagus was filmed three episodes back-to-back, so making $30 was a lot of money for a 15-year-old like me. One day, the boss of Pony Canyon noticed me at the studio’s reception and asked me if I could rap or sing. He told me to come by his studio, and that’s how we got signed.”

Sheikh divulges that Najip was a constant pillar of support for him and Ashidiq, keeping them on track and helping them understand “the game” that is show business.

“Najip taught me to respect the audience and respect the craft, that being given a platform or a microphone is a very powerful gift and responsibility.”

Sheikh is grateful for Najip’s listening parties too, which he recounts re-energised him as an artist.

“Years of giving as an artist can be tiring. The albums and magazines that Najip brought back from overseas refreshed us. This was a form of education that exposed us to new scenes and arts happening abroad and influenced us. Najib didn’t bring it back for any one specific person but to share it with everyone.”

Inspired by Andy Warhol’s factory parties, Najip also began holding whimsical parties in the ‘90s. As more young Singaporeans returned from living overseas, Najip saw this as an opportunity to ignite conversations around art.

“I had quirky installations at these parties, like once I had a painted cow, and I invited all sorts of musicians from saxophonists to tabla players to perform. Friends like (music pioneer) Chris Ho, (fashion designers) Wykidd Song and Ann Kelly would attend, and in our chats, everybody had a unique point of view because they shared their experiences in different countries.”

It was this sense of community that Najip helped nurture in the ‘90s—something that still endures today in the spirit of artistic freedom and collaboration thriving in Singapore’s alternative arts scene.

“What’s important is to make a profound connection with your tribe,” Najip affirms.

“Champion your ideas with passion and find ways to constantly ignite your inner passion, because passion is a living thing. That’s what I advise young people.”

Defining Malay Entertainment

These days, Najip continues to nurture young talents. Together with his creative collaborators, he’s introducing new talent competition formats for local TV and social media. He’s almost 60, but his vitality suggests he has many more shows to champion, just as he did with Asia Bagus.

He tells me that his long-term objective has been to help Singaporean Malay entertainment come into its own. It evidently has, with entertainers like Aaron Aziz, Fakkah Fuzz, Fariz Jabba, Nurul Aini and Taufik Batisah garnering international fanbases in recent years.

Having witnessed the evolution of Singaporean media over four decades, he feels that it is his responsibility to share with young celebrities what it takes to craft an impactful and sustainable entertainment career.

When Singapore’s Malay-language channel Prime 12 was rebranded to Suria in 2000, Najip was asked to be the face of the new brand. Already a household name and experienced producer, he was given the liberty to create his own programmes.

With this creative freedom, Najip decided to distinguish Singaporean Malay entertainment, just as Malaysian and Indonesian entertainment established themselves with distinct formats and identifiable traits. It’s clearly something that he feels strongly about.

“I gave my life and all my passion to creating forms of entertainment that would resonate with Singaporean Malays and the 350 million Bahasa speakers of the region—and I am glad that this also gave jobs to hundreds of people,” he says, reflecting on his career.

“Perhaps my proudest achievement is giving some meaning and purpose to people around me, and I am happy that I can still do what I love and love what I do at almost 60.”

Najip still feels driven to create distinct local content, which is also what motivated him to start his company, Dua M Pte Ltd, which is a production house that he uses to champion passion projects and nurture thinking artists.

“What is Malay culture? Can it be something that is not ronggeng (a Javanese dance that is accompanied by poetry)? Or perhaps I should combine dance music with ronggeng?” he questions out loud.

“Creating something unique is something very scary to do, but the Japanese taught me their culture of interpretation, and while working on Dick Lee’s Mad Chinaman, I tried my hand at combining modern and traditional elements.”

“There’s a word ‘Meraki’ in Greek, which means to do things with love and dedication, and to put a piece of yourself into your work,” remarks Najip.

Meraki

As much as we who remember Najip’s glory days in the ‘90s like to reminisce about the past, he emphasises that we should not romanticise any era of the arts and entertainment.

“Let’s not be sentimental. After we define an era, let it go and move forward. I am grateful that I am seen as a point of reference of my era. Every generation creates its own traditions, but there is no revolution without personal evolution.”

Besides Dua M productions, Najip has also been working on music-themed programmes with Suria like Berani Nyanyi and Kaki Nyanyi. He also works with a collective of young people called Oonik, which scouts and promotes talents from around the region.

“Collaboration is the only way to success because our industry is small and everyone matters. It’s not about being shiok sendiri (Malay for ‘self-indulgent’) but about collaboration, because many people around you are responsible for your success.”

Cassandra Spykerman, who was a contestant on the first season of Berani Nyanyi and returned as a guest judge on the second season, feels indebted to Najip and his emphasis on collaboration.

“He’s definitely built confidence in me since I took part in Berani Nyanyi. Whenever I see him, it’s always inspiring to watch him in his element. He’s forward-thinking and open-minded,” she gushes.

“Najip is an icon, but he is always willing to share his knowledge with people who are hungry to learn. I consider him a living legend lah, the guy is simply one-of-a-kind.”

I pose my final question to this living legend: What if he woke up one morning, hindered by age, impeded from expressing himself as fully as he still can today?

“I think I would still find some other way to create and express myself,” he replies thoughtfully.

“Because every day when I wake up, I look around and find things that inspire me. Things that keep me going.”