All images by Isaiah Chua for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

“This can’t be happening.”

That’s what Wak Sadri thought to himself in 2015 when he got the call that his son, Emyr Uzayr, had been caught in an earthquake overseas.

Sadri’s father had just passed away a month before. The possibility of losing his 12-year-old son as well filled him with dread.

Emyr was in Sabah on a school expedition, a special trip for Tanjong Katong Primary School’s student leaders. Nothing was supposed to go wrong.

And yet, Sadri was receiving calls from friends about a 6.0-magnitude earthquake that had hit Mount Kinabalu—exactly where Emyr and his schoolmates were supposed to be. He checked the news, hoping for a false alarm. But it was very real.

As he broke the news to his wife and daughter before they frantically rushed to Tanjong Katong Primary School, he expected the worst.

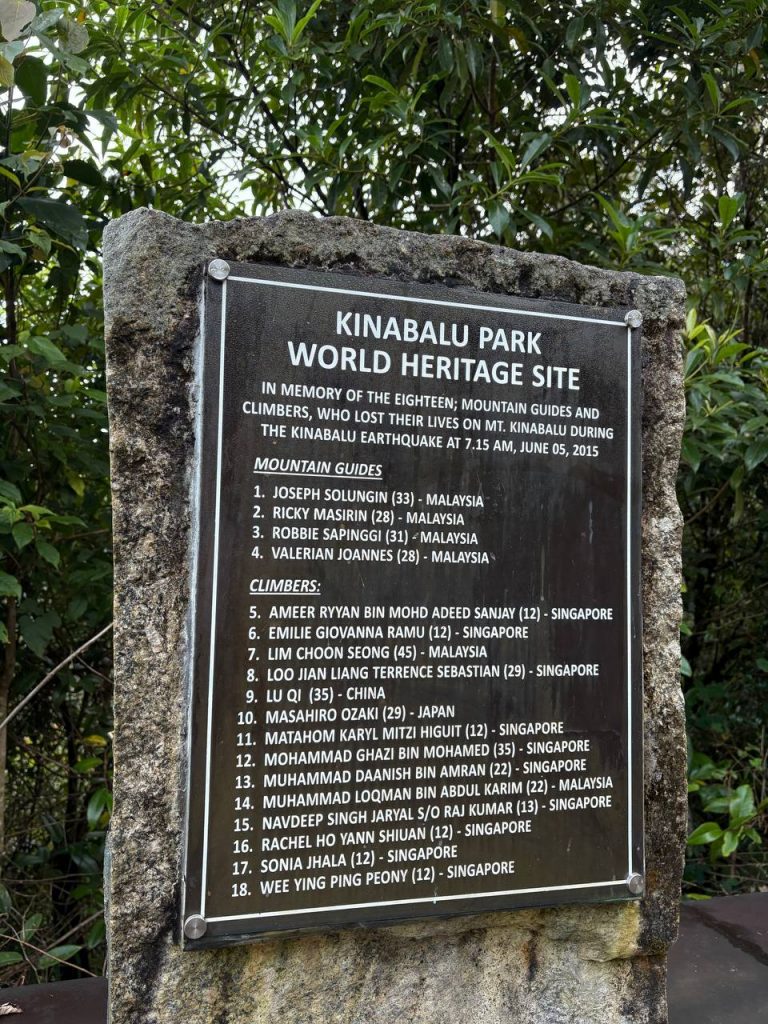

The family didn’t know it then, but the quake took the lives of 18 people on the mountain that day. It included seven pupils, two teachers, and an adventure guide accompanying the primary school group.

“I never told my wife and daughter this, but I actually pictured myself carrying Emyr home in a body bag,” Sadri says grimly.

Even as he recounts the experience today, it remains a discomfitting mental image. The 46-year-old father shakes his head, as if to get rid of it.

“I really did not want that.”

Emyr survived. But knowing how close he came to death shook the family to its core.

A decade later, Emyr, now 21, has returned to Kinabalu’s summit in search of closure—for himself, and for the family who has carried the weight of that day alongside him.

The Day the Mountain Shook

When we speak at his parents’ eclectic vintage store, Treasure At Home, Emyr has already done a string of media interviews about his return to Kinabalu.

We’d actually met for the first time last year when I interviewed his dad about his Kapo Building shop. The lanky young man was bright and charming on first impression. I’d never have guessed he went through something so deeply traumatic in his childhood.

I feel bad asking him to dredge up the incident once more, but he flashes a big smile.

“I actually find comfort in sharing,” he reassures me.

Back in 2015, he and his friends had been specially selected for the Kinabalu expedition. The group of 29 students were student leaders and had outstanding grades—the cream of the crop of Tanjong Katong Primary School.

On the morning of June 5th, 2015, the students, split into five groups, had made their way to the Via Ferrata Trail on Mount Kinabalu.

A via ferrata, which translates to ‘iron road’ in Italian, is a common mountain climbing fixture. These protected routes usually feature steel cables fixed to the rock face, as well as other fittings like rungs or bridges.

The route at Kinabalu was on a steep slope. With each group clipped to their respective cables, there was no overtaking. Emyr, who was in group two, recalls how they were egging each other to climb faster as they advanced upwards in a single file.

“All of us were laughing and joking around, telling each other, ‘Hey, hurry up, move up. Move faster. Don’t be a coward’.”

All of a sudden, there was a loud rumbling, which sounded like thunder. But there were neither storm clouds nor rain. Emyr looked up only to see a boulder the size of a van tumbling from the mountain, headed straight for groups three, four and five.

The whole mountain shook. A deadly hailstorm of rocks suddenly came pelting down on everyone.

Reacting quickly, a teacher yelled for everyone to lie down. Instinctively, Emyr dropped to the ground, turning his back towards the flurry of rocks.

To his left, a fellow student couldn’t lie down in time. She was hit in the head and neck by the sharp, unforgiving rocks, some of which were the size of car tyres. He could tell she was dead.

“I was shocked. I just kept looking down. Rocks were hitting me behind my helmet, my back.”

His backpack provided some protection, he says, but he didn’t know if the next rock would crush him.

“I looked down, praying. I even said the shahada (Islamic declaration of faith). I was prepared to die.”

After what seemed like 30 seconds of rockfall, the mountain stopped shaking. The dust settled. He was alive, but in a daze.

At this point, Emyr says all he remembers is a mountain guide spotting him—he happened to be wearing a neon orange shirt. The guide helped him down the trail.

“I was walking over my friends’ bodies along the way. I couldn’t see clearly, but what I could see back then were colours everywhere—colours of my friends’ jackets,” he says quietly.

“Some of them were down at the starting point already. It meant that the rocks were sharp enough to cut their ropes off. There were limbs everywhere. Bodies cut everywhere.”

Amid the devastation, Emyr says he didn’t even realise that his helmet had broken in half, or that he was bleeding from his head.

The local guide brought him to a hospital—they had to hike down 8 kilometres to the foot of Mount Kinabalu as it wasn’t safe for helicopters to land yet—and he finally found one of his teachers there.

It was nightfall by the time he was escorted into surgery to patch up his head.

“They put me under. I still remember the feeling. It was shiok lah,” he remarks, a brief moment of mirth crossing his face.

“After all that pain, there was finally relief.”

A Parent’s Nightmare

Meanwhile, it was absolute chaos at Tanjong Katong Primary School, Emyr’s mother, Yana, recalls.

She remembers receiving a call from the school at work saying her son was “hurt but everything is okay”. The anxiety, however, really took root when she and Sadri arrived at school to see wailing parents.

The students also had their mobile phones taken away during the trip, so none of their parents could reach them directly.

Some parents who decided they weren’t going to sit around waiting made their own arrangements to rush down to Sabah immediately. Others parked themselves in classrooms, feverishly refreshing the news sites.

Information arrived in bits and pieces. They’d been told they had to wait for the next SilkAir flight out to Malaysia. Later, it turned out they would instead take the Republic of Singapore Air Force’s C-130 Hercules—typically used for relief and aid during natural disasters—to Sabah.

At first, they were told Emyr was fine except for a leg injury. In the absence of concrete details, they filled in the blanks.

“They said his leg was injured. I was afraid he might have lost a leg. And I had just bought him a new football,” Sadri chuckles darkly.

It was a few hours later that they were told that Emyr also had a head injury, and the hospital in Sabah was seeking their consent to perform surgery.

As they flew out to Sabah on the military jet, Yana recounts how distressing the flight was.

Naturally, she and Sadri were worried sick about Emyr. But there were other parents who had already received news of their children’s deaths. Some had kids who were still missing.

“We didn’t know what to say to those who had lost their kids. Their eyes were closed, but you could still see their tears flowing.”

True relief only arrived when they finally met Emyr after his surgery.

“Even after everything, he smiled when he saw us,” Sadri mentions.

On his end, Emyr has a more lighthearted recollection of the reunion. He remembers waking up to see his parents by his side, with the feeling right there and then that everything was fine.

“One of the first things they told me was ‘You don’t have to study for PSLE. Don’t worry about doing well’,” Emyr recalls with a laugh. He was due to sit for the national exam just six months after the accident.

At that moment, he hadn’t really grasped the full gravity of what he’d gone through. But his parents knew that this wasn’t something you simply get over in time. Yana remembers what went through her mind.

“He told me when he woke up: ‘I saw everything.’ I knew then that I just had to be there for him and support him.”

The Aftermath

Emyr and his parents both grappled with the lingering aftereffects of the incident, albeit in different ways.

For Sadri and Yana, it was a wake-up call to change their parenting style. They decided to prioritise happiness over academic achievements.

Before the incident, Sadri would sit down with his son and force him to study. Emyr remembers him being a strict dad who sometimes resorted to using a belt.

But the Sadri that’s in front of me today looks very much like the Fun Dad. As I speak to Emyr, the former policeman potters around in the background, teasing his 19-year-old daughter by singing a silly song.

“We don’t pressure our children anymore. They could ‘go’ at any time. And once they’re gone, they’re gone forever,” the father says.

“If he’s talented, he’s talented. If he’s stupid, he’s stupid,” Sadri offers bluntly. “No point forcing it.”

Since the earthquake, both parents have supported Emyr in everything he wanted to try, like football, and let him pursue anything he wanted to study.

(To their relief, Emyr went with a pragmatic choice: studying finance at the National University of Singapore).

He’s been a sensible kid all along, but it seemed like Emyr grew up overnight after the incident, Sadri and Yana tell me. Their son took it upon himself to study hard, even without any nagging. Personality-wise, he appeared more sure of himself, more confident.

But behind his strong front, Emyr had struggles of his own.

At 12, he didn’t really fully understand the concept of death, loss and grief. And so he struggled to understand why he’d made it while his friends—who were smarter and better than him, by his own admission—had perished. All signs point to survivor’s guilt.

Adding to the tragedy was the fact that he and his friends had gotten closer during the trip, he says. On the bus to Kinabalu, one friend had told him about his goal to care for his single mother and sister. Just the night before, he’d prayed together with another friend, Ameer Ryyan, for a safe hike.

Neither made it. And these losses weighed heavily on Emyr.

At each milestone in life over the decade since, he couldn’t help thinking about his friends who should have been next to him.

Even when he was taking his PSLE six months after the incident, he and his fellow survivors were thinking, “Let’s do it for them”.

Somewhere along the way—he’s not sure when—he began seeing his survival in a positive light. He’d been given a second chance at life. He was determined to do his best at everything. It was his way of honouring those who didn’t make it and making the most of the extra time he was blessed with.

Emyr shares a theory: like him, many of the Kinabalu group have turned their trauma into fuel.

He muses that they’ve gone on to pursue great things. Some are studying law, others are scholarship recipients. Several are studying abroad at prestigious universities.

“I’m the least high-flying out of the group,” he says jokingly—though he really isn’t doing too shabbily himself.

Even though they all appeared to be doing well, Emyr still had an unfinished task. He’d never actually summited Mount Kinabalu.

Despite all the counselling and support Emyr received, Yana shares that they knew what her son really needed for closure was to climb Kinabalu again one day. The parents knew this long before he even brought it up.

Sure enough, soon after the accident, he declared to his parents that he wanted to return to Kinabalu someday. So when Emyr chose to make the climb in May 2025 with fellow survivor, Prajesh Dhimant Patel, no one around him was surprised.

He’d been talking about it for the last decade.

The Climb

The climb was actually the first time he’d seen Prajesh in years, Emyr confesses. But it didn’t feel awkward. It was more like a reunion of two old friends.

The pair set off from Timpohon Gate near the base of Mount Kinabalu on May 20, 2025, reaching Laban Rata Resthouse after a six-hour trek. It was the same place they’d stayed a decade ago as kids. After a short rest, they prepared for the final leg of the climb to the summit.

However, on May 21, their plans were briefly disrupted when a park ranger informed them that poor weather conditions and safety risks would prevent them from continuing the ascent.

“We were so sad. So disappointed. So angry. We went back to our rooms, but we didn’t sleep at all that night,” Emyr says, his voice rising. At that point, they thought that they would have to call it off and prepare to descend that morning.

Sadri and Yana, who were keeping up with Emyr’s climb from Singapore, thought they might have to clear their schedules and reattempt the climb with Emyr another day (they say they were fully prepared). But Prajesh had the bright idea to extend their trip.

Everything happened incredibly serendipitously, Emyr says. He and Prajesh booked the last two slots for the summit climb in the early hours of May 22. This meant they could spend the 21st exploring the vicinity of the guesthouse instead.

One of the guides, Cornelius Sanan, who had guided their group in 2015, asked if they wanted to revisit the old Via Ferrata Trail—the scene of the accident. There’s a new Via Ferrata Trail on the mountain, Emyr explains, but the old trail was never reopened because of the damage.

Seeing the rocks on the closed trail, Emyr finally understood the severity of the quake.

“I thought it was only like a few rocks, like a hundred. But there were thousands of rocks. There were rocks the size of a bus. How did we even survive that?”

When tragedy struck a decade ago, it was almost like he had tunnel vision. He was just focused on surviving. But to revisit the site and see clearly just how bad the destruction was, it truly sank in: Emyr and Prajesh had been extremely lucky.

In the 10 years since the accident, he hasn’t really discussed what happened that day with the other survivors. Perhaps this silence was because they didn’t want to trigger traumatic memories in each other, Emyr believes.

But the unplanned return to the accident site felt like exactly what he and Prajesh needed. Closure.

When they reached the mountain summit the next morning, it felt like the perfect finale. The rainclouds had finally cleared up, and they were greeted by a beautiful sunrise.

Emyr hadn’t expected to cry. But the tears flowed freely. “I felt so light. After 10 years, it’s finally done.”

“It was cathartic. I think it was like a release of all those suppressed emotions and an acceptance of the future, acceptance of the past, and a renewed sense of purpose. Now, it’s on to the next goal.”

How Tragedy Shapes a Family

Most people think survival is the end of the story. That once you make it out alive, the worst is over. But Emyr has spent the last ten years figuring out how to live.

There’s something incredibly impressive about the way he’s done it. At such a young age, he had to confront a question most people never do: What do you do with a life you didn’t expect to still be living?

His answer: Don’t waste the life he was given. These days, Emyr volunteers for a range of causes, from Meet-the-People Sessions to the Early Education Fund, which supports families of children affected by incarceration, and M³, which helps low-income Muslim families.

He also pitches in at his parents’ famous vintage store whenever he can.

“Instead of asking, ‘Why did I survive?’ I tried to make it mean something,” he reflects.

“I was given a second chance. So I put pressure on myself to live up to it. Sometimes, too much pressure.”

Emyr’s still figuring things out. He’s only 21, after all. But his story shows what it means to live with trauma—and to live well.

Survival isn’t just a solitary act. It’s shaped by the people who shed light in your darkest times, who sit with you through pain and trauma. Yana remembers the nights after the quake, when she had to soothe Emyr back to sleep after his nightmares.

In a way, with their unwavering support, Sadri and Yana held their son together. And they’re still holding him, even now.