I have a fair idea. Instead of celebrating his creative vision, business acumen, or some say genius, the obituary would probably fixate on his—wait for it—resilience. The writer would devote pages to how Mr Jobs had ‘bounced back’ from ‘setbacks’ like his departure from the Macintosh group, or the dramatic failure of Apple III.

There would be long paragraphs on the struggles of growing up in a single-parent household, and even longer paragraphs on his darkest moment—accidentally making an iPhone which bends.

In the conclusion, we would celebrate his inspiring story of resilience, grit, and a ‘never-say-die’ attitude. We would then conclude that Apple’s success would not be possible without Mr Jobs’ hard work and sacrifice.

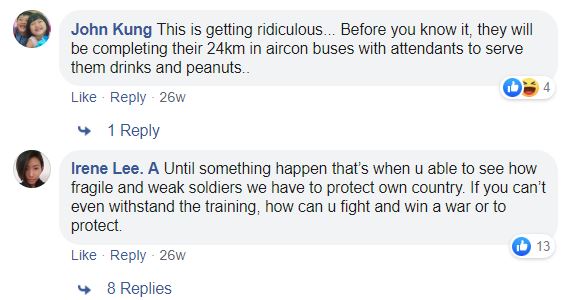

The media preaches it ad nauseam and so do many of our public servants. Worst of all are the Keyboard Enciks, who love to crucify kids for being ‘soft’ or ‘entitled’, when in fact, most of said entitled brats are trapped in circumstances beyond their control.

Take, for example, the perennial problem of heat-related injuries during National Service. It is a danger which cannot be completely eliminated in tropical Singapore. Nonetheless, we should try because one deceased soldier is one too many, and there’s no reason why better safety measures cannot help. Only the likes of a total nincompoop would be opposed to better training safety.

Yet nincompoops abound. Every time Mindef tries to work on its safety by altering the equipment or temporarily suspending exercises, they emerge out of the woodwork to KPKB. Such prudence, they argue, would lead to falling standards, soft soldiers, and eventually, the doom of us all.

Remember Sutachi? Remember the two young hawkers who put up $15,000 of their own money to set up a stall in Chinatown? I certainly do. Or at least I remember the aftermath when they announced their closure, after struggling for a year and failing to make a decent salary.

Instead of sympathy, they got scorn. Netizens criticised them for setting up a fusion cuisine stall in a neighbourhood like Chinatown, for putting ‘passion’ before economics, and for having the temerity to charge $7.50 for a single bowl. While some thanked them for having the guts to try, others despised them in spite of their striving.

University-educated? Japanese fusion cuisine? They should be frying char kway teow or making laksa instead! How dare they bring such western influences into the sacred space of the Hawker centre!

Clearly, resilience is not the real question here. Sutachi’s young owners have plenty of it, but it doesn’t matter in the light of a far graver crime: challenging tradition.

Firstly, a tendency to worry constantly about the declining resilience of today’s youth.

Secondly, an equal and opposite tendency to celebrate ‘toughness’ as the singular cause for our present-day success; often at the expense of all other qualities like cunning, ingenuity, rebelliousness, or even luck.

Grit is always the reason for all that’s good and well about Singapore and the source for all the good that’s yet to come.

This leads us to the first problem: ahistorical thinking which locates all virtue in an imaginary past. In this Disneyland version of our forefathers, everyone worked hard, and thanks to their ‘blood, sweat and tears’, Singapore had a strong foundation upon which its present-day success was built. Therefore, both our Merdeka and Pioneer generation websites salute the older generation for their hard work—and nothing besides.

I say this not to belittle their contributions, but surely there is more to Singapore’s past than hard work and more hard work? What about the opportunistic, the daring, and the totally unconventional? What about those who took risks to start new businesses or used their connections ruthlessly or simply had the balls to do what no one else dared?

Not everyone in the 1960s toiled like pack animals. Work and success in the past were not so different from work in the here and now. Ambition, opportunism, and innovation were just as important in a 1960s SME as they are for the co-working, latte-sipping start-up of today.

Having spent a fair amount of time in western countries, I can attest to the fact that Singaporean youth work much harder than many of their counterparts abroad. Students study longer and harder. They juggle expanded syllabuses, extra-curricular activities, and self-learning outside the classroom. Holidays are not real holidays because they are filled to overflowing with internships and CIP projects and part-time hustles, which serve to make them more employable in the future.

Our test scores are high, and our working hours are even longer, because everyone has (reluctantly) embraced the Darwinian logic of our free market.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Check out the Youth STEPS study, a longitudinal research collaboration between the National Youth Council and the Institute of Policy Studies Social Lab. When more than 4,000 youths aged 17 – 24 were surveyed in 2017 what they saw as the key ingredients for success, hard work ranked as one of the top three responses, sandwiched between ‘attitudes and values’ and ‘drive and ambition’.

But for all the effort that’s put in, youth today are still widely derided as snowflakes and strawberries. The reason is not that complicated: our attitudes towards work-related issues have changed.

Millennials today are simply more vocal about stress, anxiety, and mental health issues. And thanks to social media, these voices are greatly amplified. What was once a lament limited to the Kopitiam now has the ability to reach thousands, if not tens of thousands. This norm of self-expression (or it self-promotion?) naturally leads to a mistaken assumption that kids today are weak, soft, and unable to overcome obstacles.

Complaining, of course, has little to do with resilience or lack thereof.

Furthermore, well-educated youths in possession of desirable skills are naturally able to pick and choose their jobs. In a free market, they are not shackled to a toxic workplace or obliged to stay when opportunities for advancement are limited.

This has little to do with strawberry-ism or (lack of) resilience. Grit is surely not the tolerance of unnecessary suffering for less money and longer hours.

To believe in such a false binary of ‘present weak, past strong’ is a sort of Trump-ian argument deserving of criticism. What is it, if not an escape into a romanticised past, so as to avoid facing the difficult challenges of today?

The question is not why NSFs today are so soft, but what can we do about the suffocating ILBV and the hotter climate.

The question should not be why kids are so easily stressed, but how to create a learning environment where more forms of merit can be recognised.

This constant anxiety about toughness and grit helps absolutely no one. The future will demand more from us than sheer grit, and obsessing over its existence or lack thereof in the present-day is a lazy way of dealing with pressing, complicated challenges with no easy answers.

We can, of course, bite down and endure the economic crisis, heat injuries, cancer, lack of opportunities and mental health issues. But that’s not resilience. That’s masochism.