Is Singapore Tired of Hawker Culture Discussions Already?

Ah yes, Singapore’s hawker culture — the perennial point of conversation since the day Malaysia decided they wanted nothing to do with us and our rendition of Nasi Lemak.

A while back, my colleague Edoardo penned his incredulity that a bastardised chicken curry— amid a flurry of other more pressing issues—would be the thing that warrants national concern. He cited a CNA commentary that said “few things define us as a country as much as food does.” You could interpret that as “Singapore doesn’t have a distinct culture the way other countries do, so we cling to food as the basis for our identity”.

Hence, if we were to take hawker culture as the only (or at least, the main) culture in Singapore, it’s persistence as a hotly debated topic is not without reason. Between becoming a forgotten trade in a stereotypically Asian pursuit for white-collar jobs over physical labour and the pandemic sweeping away hawkers’ rice bowls for prolonged periods of time, I think we have long come to the collective agreement that Singapore’s hawker culture has to be preserved.

But the same way eating chicken rice every single day for lunch will soon wear even the biggest stans down (unless you’re the admin behind A Different Picture of Chicken Rice Every Day), the countless articles and social media posts discussing the importance of keeping Singapore’s hawker culture alive feels like it’s starting to lose its meaning.

We can go on about how hawkers can’t sustain themselves if they’re charging us next to nothing, but it sure as hell seems hypocritical to talk about saving hawkers when we’re not willing to pay more. The entire rhetoric about hawker centres and their value almost feels like we’re just talking out of our asses.

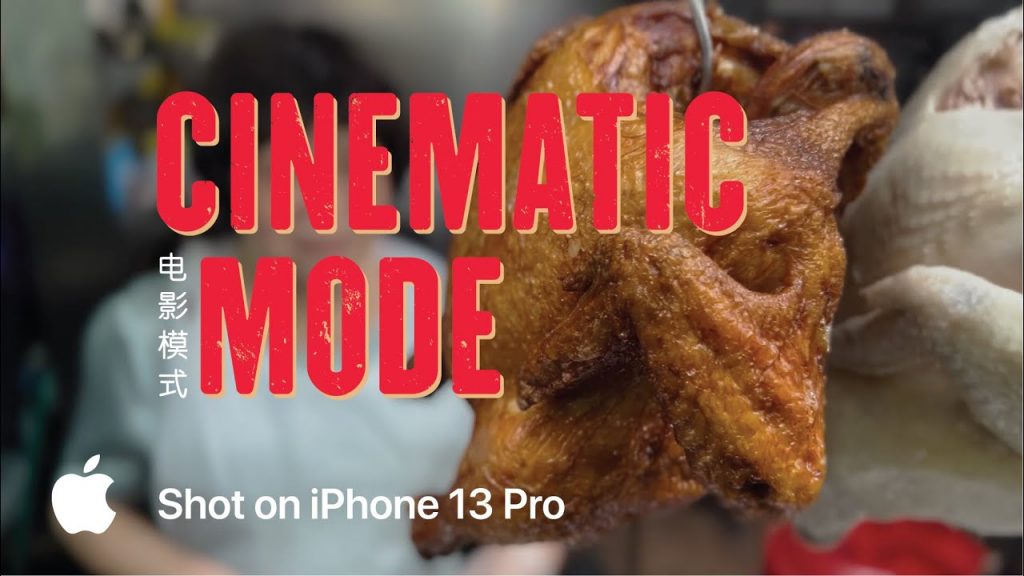

So I reached out to a couple of content creators who took part in this year’s Shot on iPhone run, coincidentally centred around Singapore’s hawker culture, with a penny for their thoughts on the importance of continuing to document the aforementioned topic — and if Singapore’s tired of hawker culture discussions already.

My motto for many years was “Eat soon kueh soon before it’s too late”. Given the importance of hawker culture to us (you can criticise our political system or education system but don’t ever criticise our food), we don’t just need to document it. We need to celebrate it. Singapore’s hawker culture has to preserved.

It’s an integral part of our social fabric and forms the soul of Singaporean cuisine — there are few experiences that come close to giving you that same type of low-grade anxiety as trying to order different variations of the same dish from an impatient hawker during peak hours. Hawker culture is also, to me, one of the ways edges of the different ethnicities blend together to create something unique to us. Growing up, my mother would buy breakfast from the nearby hawker centre — chai tow kway, lontong, putu mayam etc. It wasn’t a Chinese breakfast or an Indian breakfast, it was always a Singaporean breakfast.

This blend is so beautiful to me, so, no. The topic of Singapore’s hawker culture is not overexposed. If we don’t keep hawker culture alive, we’ll come to regret it when we lose it. Talking about it, taking videos and capturing bits and pieces of it, is my way of cherishing what we often take for granted. So eat soon kueh soon before it’s too late.

Willin Low, 50, is a lawyer-turned-chef serving up Mod-Sin cuisines under Wild Rocket Group. His videos capture a new-generation hawker who took over the reins of the Prata Saga Sambal Berlada at Tekka Centre from his father, a symbol that all is not lost yet.

It is human nature to tend to treasure things only when it’s gone. Because Singaporeans live a very fast-paced life and get access to so many other formats of food, we don’t realise that hawker food is a rapidly dying trade. As I went around taking photos, I realised most hawkers are in their late 40s or older. I don’t see many young adult hawkers around, and it’s sad knowing that food traditions may be lost forever without a successor.

When I spoke to the septuagenarian owner of a BBQ chicken wing stall, she said even though her kids have been telling her to retire, she didn’t want to because [running the stall] is the last meaningful thing she could do in her life. She offered us free wings after that.

I can see that hawkers are very genuine and appreciate every single customer that visits their stall — there’s this kampung-like vibe going on. In a way, hawker culture to me connects our past to our present and hawkers are the ones shaping our cultural identity. Hawker culture is more than just food, it’s our heritage.

Rather than calling it overexposed, even more can be done to educate others about the importance of hawker culture. By doing something as simple as taking a photo and posting it online, we can shine a global spotlight on Singapore’s hawker culture and boost the demand for hawker food, hopefully attracting the younger generations to take over the hawker trade to support the growing demand.

Tan Chun Rong, 30, is a professional photographer and food stylist with a passion for capturing the cooking processes and techniques. He hopes that his works will pay homage to hawker predecessors by preserving their techniques through photography.

I often think about the rising costs of living in Singapore, and how it relates to the prices charged by the hawkers. Hawkers are urged not to raise their prices while utility prices and GST go up. With these unrealistic expectations, doesn’t that mean hawkers have to sacrifice and take the hit on behalf of the nation?

The multiculturalism, the crazy organised mess and each individual stall represents a tiny little cell that makes up the entire being that’s ‘our country’s belly’, and given the greater cultural significance endowed upon hawker culture, how can we translate discussions into government and community action to preserve it? An ideal scenario would be a thriving hawker culture with a good mix of young and old hawkers to keep the ecosystem going, and to get there we’ll need more discussion and more action — even if it’s just by shining a light on the prep work that goes on before the stalls open.

The Americans sell the American dream, the Japanese with their Anime and Manga, and the Koreans with their K-pop. And our hawker culture is uniquely our own. When we start sharing with the world what makes us unique, it elevates our standing in the world.

Chai Yee Wei, 46, is a filmmaker and producer. Beyond hawker centres and hawker culture, he also fears that wet markets will slowly disappear as the country becomes more ‘modern’.

Even though I work in the food industry and research hawker culture, I’m guilty of eating hawker food mindlessly.

In a country as food-obsessed as Singapore, we don’t think about the work, history and craft that goes into it. Especially now that we rely so much on deliveries, we forget the people behind the food.

We get hung up on the years that a Japanese sushi chef has spent perfecting their knife skills or the restaurants that a Cantonese chef has worked in.

What about the time a hawker has invested into their craft — the way lor mee hawkers master the ratio of starch to gravy for the perfect thickness or the way a curry puff is crimped shut for maximum crunch?

If you think more deeply about the dish and its history, it makes the meal a little different, a little more special. These are all things we should remember every time we eat hawker food, and I think capturing moments like that on our phones help us celebrate them.

As it is, I think the topic of keeping hawker businesses alive keeps coming up because we haven’t really figured out a solution. With the way the past few years have panned out, we never know when certain dishes or hawkers stalls, along with their stories, will become a thing of the past. I don’t have the answers on how to make hawker trade a sustainable one, but I think just having the conversation alone is vital to the process.

Sarah Huang Benjamin, 33, is a chef, content creator and heritage researcher. It still blows her mind that everyone carries a high-quality camera around in the form of their smartphones nowadays, essentially turning them into storytellers with every photo or video they take.