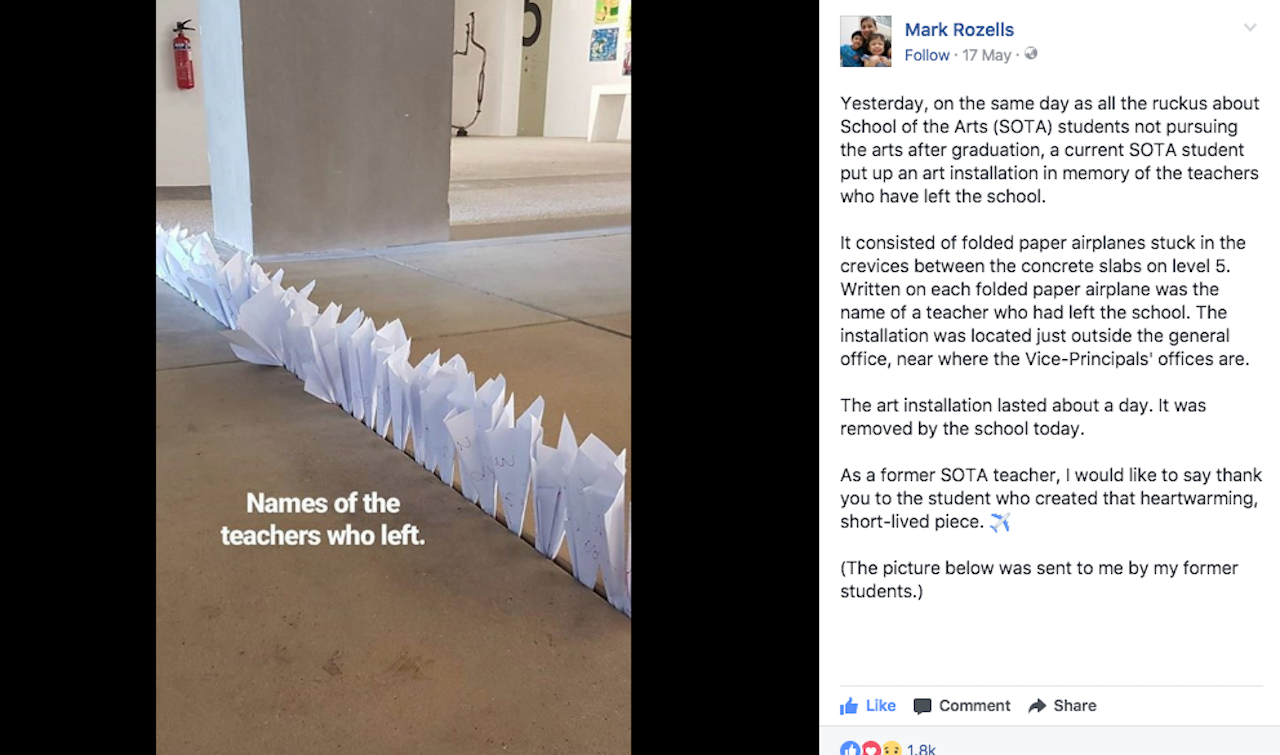

Top: Taken from Facebook

Like art, courage exists in myriad expressions. Last week, Calleen Koh chose a paper airplane to express hers.

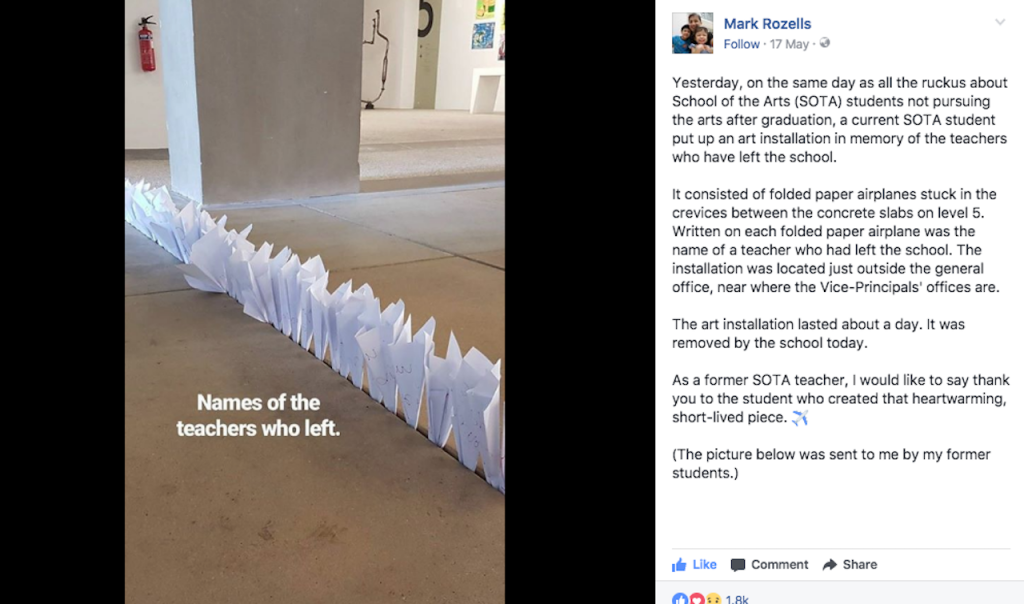

The Year 6 Visual Arts student from School of the Arts (SOTA) stuck several paper airplanes into the crevices between concrete slabs in her school, each carrying the name of a teacher who had left. She had not sought approval to do so, even though the art piece was was part of a Performance Art Masterclass where students were instructed to create a site-specific performance piece. The next day, her art piece was promptly removed for not complying with SOTA’s guidelines.

Though her powerful art piece was a symbol of rebellion against the system, and its removal a sign that rules and regulations still trump in Singapore, perhaps she has this same system to thank. After all, the beautiful irony of bureaucracy is that it creates good art. The most electrifying art is born from struggle and thrives under tension.

When I spoke with Ong Sim, chairperson of the SOTA Alumni Board, she said: “I’ve felt similar frustration when I was a student. But I believe SOTA students will always be a little more angsty than the average teen simply because ‘standing firm in what you believe in,’ as we’re constantly reminded to do, tends to manifest that way in adolescence. And that’s okay.”

Within 24 hours, Calleen’s art piece had inadvertently started a conversation about arts education in Singapore, thanks to the viral Facebook post of her work from former SOTA teacher Mark Rozells.

Because of the effective intent behind the piece, SOTA’s staff turnover rate, which remained constant over the last five years, became a hot topic. The online furor was further fuelled by recent news that more SOTA students were pursuing non-arts related fields.

But a fire only burns as fiercely as its brightest ember. In this case, the blinding irony of an arts school being subjected to standard Singaporean bureaucracy lit up forums and comment sections.

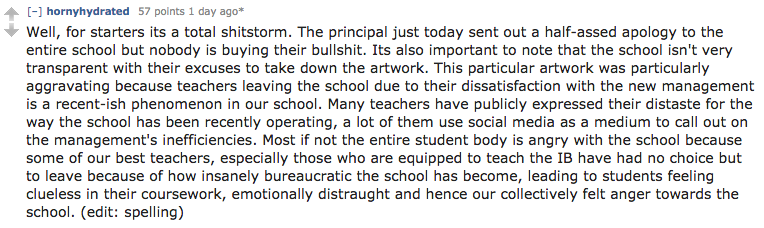

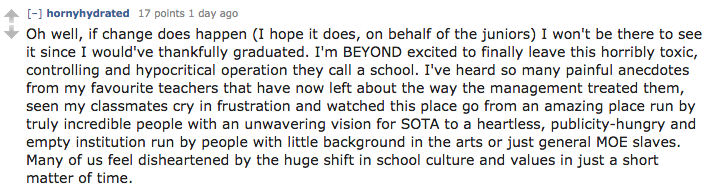

On the Reddit thread about the art piece, a current SOTA Year 6 student, who went by the now-deleted username hornyhydrated, explained that the particular frustration around the removal of the art piece highlighted the school’s poor management. The school had become “insanely bureaucratic,” causing a “huge shift in school culture and values.”

In contrast, both Rozells and Ong Sim attest to SOTA’s open-minded nature. The latter also stated that it wasn’t uncommon for rules to be abolished or changed when students made a convincing case.

Ong Sim surmised. “Isn’t it the mark of a true creative individual or artist to be able to achieve what you set out to do within the very boundaries presented to you? What good is an artist who has carte blanche or tabula rasa?”

While this may sound provocative, it’s difficult to disagree. After all, knowing how to cleverly navigate the nuances of bureaucracy only benefits oneself in the long run.

Rozells, who is currently Head of Language and Literature at SIM International Academy, explained: “Artists need to be smart. Calleen’s art piece was passionate, sincere but also incredibly intelligent. That comes from learning in and through the arts.”

To produce a work of art that’s thought provoking and deliberate, while balancing unbridled passion, one should be well-acquainted with the guidelines that govern large organisations. If for any reason, at least so one is aware when lines have been crossed. Calleen shared: “The school sets guidelines for art installations that are properly conveyed to all students. I was aware of the attention I could get from putting up my piece, but I wasn’t expecting the eventual impact it had on the public.”

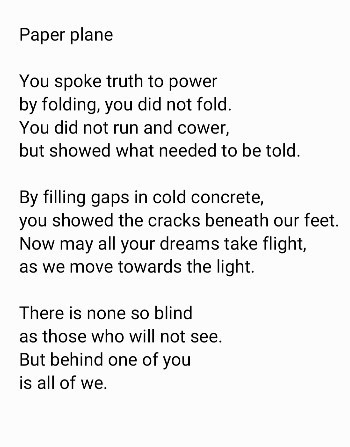

Rozells expressed the public’s general sentiment in a poem to show support for those, like Calleen, who use art to make a point, especially if it means going against the odds.

Unsurprised but heartened by how much the art piece resonated, he said: “It was a moving art piece for several reasons. Firstly, it took a lot of courage to be enacted. Secondly, it was sincere in its desire to remember the past and express gratitude for those who have gone before. And lastly, there was irony in its swift removal.”

In flourishing not just despite red tape, but because of it, these individual stories coming from SOTA within the past week remind us that good art is made great with challenges and hurdles. And great art starts a conversation. It forces us to confront the good, bad and ugly. With Calleen’s paper airplanes, we were given a reality check that life is not always easy and things like bureaucracy are a necessary part of it, one we eventually learn to deal with.

Most of all, great art demands more from us, that we show up and fight for what we believe in. For Calleen, this may have been sheer love for her teachers, whom she admits greatly shaped the way she is today.

“As an art intervention, part of the process was to leave it out in the open, subject to any outcome from its audience – whether it was to engage or to remove,” she added.

So perhaps great art doesn’t mind the duration an art piece remains or whether we practise it in the end. Only that we boldly embrace the raw and messy truth when it questions bureaucracy, pushes boundaries, and pulls apart the seams of a society’s fabric with honest intent.

But Calleen already knew this. We’re just playing catch up.