Didi, a 33-year-old business consultant for the manufacturing industry, finds himself travelling extensively for work. Like many overseas travellers, he adheres to the unspoken law that you must buy snacks and souvenirs for your friends stuck at home.

You’re in Osaka. They’re not. Treat them.

After a while, the costs of being a jetset Deliveroo man caught up to him.

“I realised that I was actually spending quite a lot of money buying these gifts for all of my friends and colleagues back home,” Didi said, laughing awkwardly.

Pressed for time and money during one of his trips to the UK, he went to the supermarket and picked up instant noodles in lieu of ‘proper gifts’. Being a natural-born business consultant, he then tried to up-sell his cup noodles as cultural relics from a foreign land.

“Of course, we called him out for being a cheapskate immediately,” said Sue, the group’s main photographer.

But the cup noodle thing stuck and it soon became a long-running inside joke amongst the four friends, who’ve known each other since junior college. To take the piss, everyone started bringing back instant noodles from their own journeys abroad, inundating their diets with an excess of exotic MSG.

This went on for a while until the last months of 2016, when Didi proposed a website, one dedicated to the eating and reviewing of cup noodles.

“He’s full of crazy ideas like that,” said Sue.

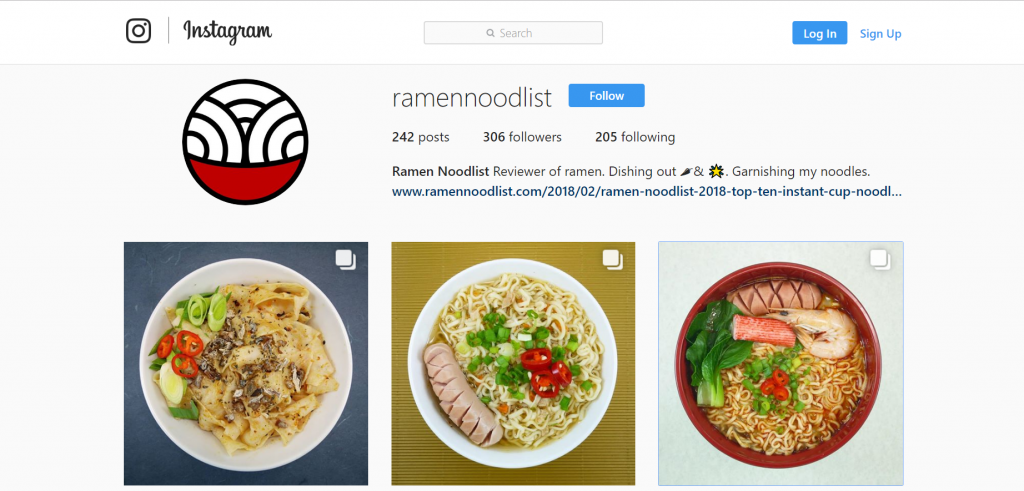

Not too shabby for four working professionals who knew nothing about WordPress or photography before embarking on this voyage. But to hear Didi tell this origin story, starting Ramen Noodlist was as easy as, well, pouring hot water onto cup noodles.

“The so-called movie moment where everything came together is when we decided on the name of our website,” he said, “After that, I just needed a few undisturbed hours to learn about web hosting. Nowadays, it’s easy to find resources online.’’

Since then, Ramen Noodlist has published more than 200 reviews of cup noodles from all around the world. Every alternate weekend, the group meets at Sue’s house with eight to 12 ramens on the agenda. Over the course of an afternoon, they cook, garnish and photograph the cup noodles before digging in to judge each product on its taste and spiciness.

According to Didi, the group rarely disagrees about the spiciness rating because they are all Singaporeans with a “similar baseline for spice tolerance”.

Taste, however, causes more dissent and difference in opinion, though never to extremes of total disagreement.

“It’s usually one or half a star difference. There’s never been a case where one person gives one star while another guy gives full marks,” said Sue. In cases where the members cannot reach a consensus, an average score is used as the final rating.

Though Ramen Noodlist began as fun project between old friends, both Sue and Didi believe that cup noodles have taught them much about the peoples and cultures that consume them.

To help me understand this, he used the example of cup noodles in China. Or more specifically, a question that used to bug him: Why Is There So Much Oil in China’s Instant Noodles?

“Back in the country’s poorer days, the oil was quite dodgy and people could not afford to use good quality cooking oil,” he explains, “Now that things are better, using lots of oil is like showing everyone that you’re moving up in the world.”

“Our subjective verdict is “too oily”, but people in China absolutely love it.”

Closer to home, Didi sees Singapore’s wide range of cup noodles as a reflection of our status as a multicultural global city. Post-Ramen-Noodlist, he expresses a newfound appreciation for Singapore’s diversity and privilege, especially when compared to neighbouring countries.

“If you go to Indonesia or the Philippines, they will have local flavours like “bulalo” (Beef Stew) or “mi goreng” plus a few well-known Japanese brands. But the range is very limited compared to Singapore. You’ll be hard-pressed to find many Taiwanese or Korean flavors unless you go to an upmarket place for expats,” he says.

This idea of instant noodles as culinary shorthand for a country’s deeper cultural values is Didi’s pet topic. He believes cup noodles can condense culture. They allow us to experience countries and cultures beyond our own.

But for every rule, there exists an exception. One unsolved ramen mystery that continues to haunt him is the existence of Samyang’s tongue-melting Spicy Ramen.

“I’ve been to Korea many times before. Their food is spicy, but not to the extent of Samyang-level “spicy”. So I’ve always wondered where did it come from? What’s the precedent, you know?” he asks.

In reply, I mumble some vague musings about Running Man and Samyang’s potential as quality television, but it’s Sue that provides the most succinct explanation:

“I think it’s a marketing gimmick like the ice bucket challenge a few years ago. One person starts it on Youtube and people just follow.

“Growing up, Maggi and instant noodles were semantically identical. And for a long time, we were stuck with the mental price point of $2,” Didi said, “Only in more recent years have we begun exploring high-SES cup noodles like A1’s Abalone noodles or Prima’s premium flavors.”

In his view, the future of cup noodles lies in the West. Asia might have experienced a ‘ramen Renaissance’ thanks to the explosive flavours of Samyang and Prima, but the West remains trapped in a proverbial stone age of artificial chicken broth.

“I think they’re getting quite sick of it already,” he speculates.

To capitalise on the virgin wilderness that is the Western ramen market, he wants to forge a ‘Grand Theory of Culinary Cultures’. In plain English, he wants to find a single ramen flavor that everyone WILL enjoy, a flavour that can capture everyone’s imagination and unite palates otherwise divided by national boundaries.

“My money is on tom yum”’ he said, “There’s something about tom yum’s sour and spicy flavor that appeals to lots of people. Even the Koreans have cooked up a Tom Yum Kung noodle and I’m quite curious to see what that tastes like.”

Sue begs to differ. Her vision of the future is one of diversity rather than unity. She thinks that we will see more ‘interesting flavours’ and ‘creative combinations’ that are totally divorced from the mundane realm of ‘normal food’ served up in hawker centres.

“We already have nacho cheese in our instant noodles and Samyang even has a Wasabi Mayo noodle. It will be something innovative or something that people have never thought of before,’’ she said, laughing.

“Maybe by 3305, we will see a chocolate-flavoured instant noodle.”