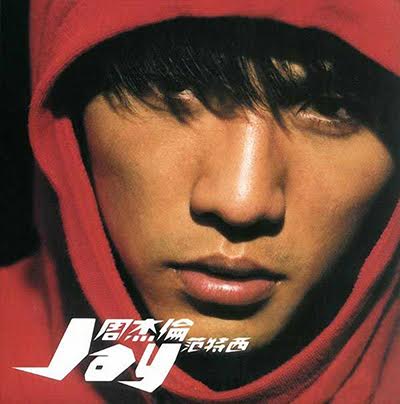

Come September, 15 years after his debut, Chou will grace our shores for yet another packed concert. While his fans have grown from 14-year olds dreaming of first kisses to mature mid-twenty somethings on the cusp of marriage, the king of Mandopop has remained just as magnetic.

To his fans, this comes as no surprise. His appeal merely reflects the larger, enduring charm of Taiwanese romance, spanning everything from film to music.

Everybody hurts

Most of our first experiences with romance, and consequently heartache, happen in secondary school. Unsurprisingly, this is when many first encounter Jay Chou’s wistful lyricism. He tells us that we are not alone in our suffering. We believe him, and grow to associate his songs with the intricacies of bittersweet adolescence.

Likewise, the admittedly formulaic genre of Taiwanese romance taps into the timelessness of love and its popular, requisite dimensions: coming-of-age, first loves, love triangles, unrequited feelings.

Remember the confusion and betrayal of watching your best friend fall for your crush? Or that helplessness in the face of a fading connection; the inexplicable joy of meeting someone’s eyes from across the school hall.

Otherwise insignificant moments like a knowing smile and the accidental brush of one’s fingers against another begin to take on greater meaning the moment we learn, by way of real life and its reflection on television, that these things don’t last.

Even in good times, we lean intuitively towards Chou’s iconic ballads (like An Jing or Qing Tian) during karaoke sessions, if only because they remind us of the first time we truly felt understood.

Arguably, few capitalise on this fundamental desire for empathy via nostalgia better than the Taiwanese. At a press conference last month, Taiwanese director Neal Wu shared about his latest movie At Cafe 6: “Ever since the start of the human race, there have been feelings and emotions. You might think love is something you just do, but there is a lot to analyse about it — things we find impossible to understand. That’s why these themes persist. Their topics can never be exhausted.”

Explaining the emphasis on life’s little things, a critic analysed: “Since 2000, the Taiwanese economy entered a period of stagnation, leading young people to pursue private joy and try to make the most of all the little satisfaction and happiness in their daily lives. Another reason [for the emphasis on small joys] is that social upheaval made young people more pessimistic about long-term great happiness.”

So move aside, education! Heartbreak is truly the great social leveler. Country singer Sheryl Crow might have quipped, “The first cut is the deepest,” but the Taiwanese have always known it is also the easiest to commercialise.

You too? Me too!

The popularity of Taiwanese romance is built on the shoulders of its relatable protagonists and storylines. It is this relatability that transcends vastly different demographics to allow the genre its widespread success.

In You Are the Apple of My Eye, Ching-teng’s feelings for Chia-yi surface only at her wedding to someone who isn’t him. The ‘should-have, could-have’ theme resonates with anyone who has ever experienced the profound regret of not following their heart.

Where storylines are concerned, the magic lies in finding the right balance between the personal and the universal.

According to TODAY, such winning recipes entail “quirky coming-of-age, puppy-love stories tinged with nostalgia and featuring awkward but lovable high school students as the protagonists.”

Looks and behaviour are equally important. Bombshell beauties à la Hollywood’s Megan Fox generally do not play leads. Instead, female leads must possess an accessible, girl-next-door kind of beauty.

Recall Michelle Chen (You Are the Apple of My Eye) and Vivian Sung (Our Times) from the abovementioned films. Their girl-next-door personas are goofy, non-intimidating and unassuming, making them ideal candidates for capturing both male and female audiences.

Guys want to be with them, and have all had crushes on girls like them. Girls, well, girls just want to be them. And these resemblances to real life are not coincidental.

Where storylines are concerned, the magic lies in finding the right balance between the personal and the universal. This involves breaking down the nuances of larger feelings like sadness and joy by projecting them on-screen in scenarios that revive specific memories and emotions. “Wow, this movie gets me,” is the highest compliment a moviegoer can pay.

Unfortunately, the most relatable theme of such movies is a lesson mostly appreciated only on hindsight: that life rarely goes according to plan, as much as we think we have it all figured out.

For all the research and think pieces done on the Taiwanese romance genre, none (if at all) have observed that they can be far more affecting than their Hollywood counterparts.

For the Taiwanese, less is certainly more. Crucial details are subtle, and plot twists are rarely overdrawn. Reciprocated feelings are more innocent, portrayed perhaps by a kiss on the cheek, leaving the audience free to paint the bigger picture in their heads.

With more room for interpretation and imagination, there is inevitably greater opportunity to draw connections to personal experiences.

The genre is comfortable with ambiguity, something Hollywood hasn’t quite grasped. Happy or closed endings are not necessary. Taiwanese films might allude to a possible future for their protagonists, or lyrics in songs might be used to tease out vague ideas. But none of this is ever explicit.

While Hollywood usually opts for a straightforward expression of ideas, symbolism is rife in Taiwanese romance.

In the closing scene of Chou’s music video for Ge Qian, the female protagonist is seen slumped on a hospital floor shortly after catching the man she loves with another woman. In one hand is clasped an equally forlorn ice cream. As it melts, it turns into a powerful symbol of one’s helplessness in love.

Speaking of the undying attraction of Taiwanese romance amidst flashier Western films, actress Cherry Ngan of At Cafe 6 feels that films like hers offer audiences something lacking: “I think there are too many international blockbusters and Hollywood films filled with special effects. Even Hollywood blockbusters are now repeating themselves … Taiwanese teen romances are very small and local, but they are about things that everyone can relate to.”

For all the merits of its subtlety, the genre is known to be predictable. Perhaps, the perfect combination of formula and nuance delivers on the expected heartache, all while facilitating the emotional navigation of that which audiences cannot control in their real lives.

Granted, we might never see a Taiwanese romance win Most Original Storyline or Most Novel Concept, but it will always win hearts. Sometimes, this is the best award. Just ask Jay Chou this September.