Top image (composite): individual photos courtesy of interviewees.

RICE does not endorse or recommend DIY HRT.

Last year’s circuit breaker was tough for everyone, but Audrey*, a 19-year-old trans woman, remembers it as two months that literally changed her life.

Then in her second year of junior college, she had been quietly struggling with gender dysphoria for years. Coming out to her parents—whom she described as ‘conservative’ and ‘sort of transphobic’—was out of the question, and seeing cisgender girls in school every day only reminded her of the body she wished she had.

“The thoughts just kept recurring that I didn’t look like them and couldn’t blend in,” she said.

When school closed in April 2020, with nothing to distract her from her spiralling thoughts, her condition worsened rapidly. “I was quite badly dysphoric, verging on suicidal,” she said. “I tried to push ahead, but I felt that if I had to keep waiting before I could get care, I might not survive that long.”

In a bid to regain control, she turned to the Internet. While she’d read a lot about transitioning, she hadn’t heard much about self-administered hormone replacement therapy (HRT), believing the medication could only be obtained from a doctor. But after talking to other trans people on a Discord server and reading up online, she decided to take the plunge and buy hormone pills without a prescription. She ordered Estrofem, a brand of estrogen pills, from an online pharmacy in Portugal, crossed her fingers, and waited.

Audrey is far from the only trans person here to have attempted ‘DIY’ HRT. I couldn’t find any local data on the topic, but numerous anecdotal accounts from trans people, as well as LGBTQ+ community workers, indicate the practice is not uncommon in Singapore, and has been around for decades. While it has evolved over the years, its causes have remained constant: desperation born of stigma and discrimination, and difficulties with accessing trans-affirming care.

“It didn’t really occur to me how stressful it could be [when I started], because I wanted so badly to do it,” said Audrey. “I just felt, if the chances of me dying without HRT are higher than me dying from it, I might as well give it a try.”

Even if you don’t know where to look, it’s not difficult to track down illicit HRT online. You don’t even need to go on the dark web. With some time, patience, and Reddit sleuthing skills, you can find a wealth of information about buying HRT, be it from unregulated online pharmacies in Russia or the Philippines, or mainstream marketplaces like eBay and Taobao.

Amelia*, a schoolmate of Audrey’s, began ordering HRT off Taobao when she was only 14 and still living in China. She subsequently switched to ordering from a ‘more legit’ online pharmacy headquartered in Vanuatu.

Now 18, she has been DIYing for almost four years. Over coffee, she took me through the ins and outs of buying HRT online, explaining how vendors would change the names of the drugs to avoid being picked up by marketplaces’ filters.

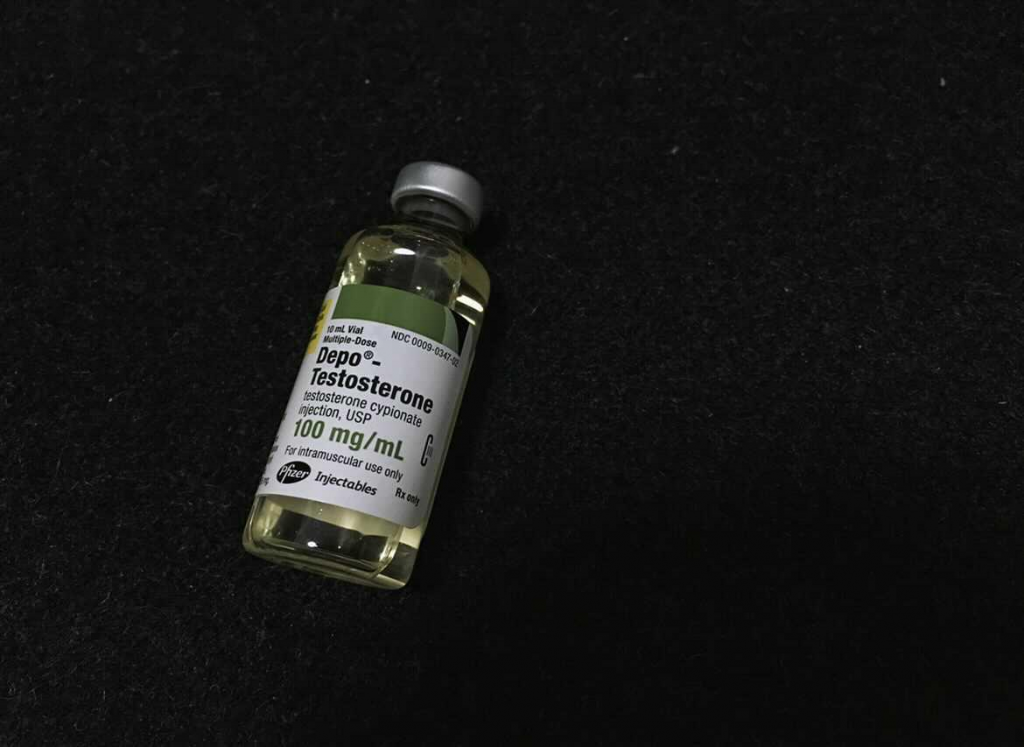

While feminising treatments like estrogen and anti-androgens can be bought online relatively easily, masculinising treatments—mainly, testosterone (T)—are more challenging to find. Dacre, a 20-year-old trans man, explained that this is partially because anabolic steroids are tightly regulated, given their potential for misuse. But also, unlike estrogen, T mostly comes in liquid form, which is taken via injection.

Although he now has an official prescription under the public healthcare system, Dacre started off buying T from a fellow trans man he met at the gym. That friend, in turn, got his supply from an online pharmacy in Malaysia, which he claimed was ‘lab standard’.

When I asked Dacre how he decided it was safe enough to use—the Internet is rife with horror stories about how fake T (in one alleged case, petrol) has been linked to the deaths of trans people—he grinned sheepishly.

“I had done some research, but in the end I guess I was kind of half-assed about it,” he admitted.

“I just trusted that his T was safe, because it worked for him. And I was desperate and curious. [My thinking at the time was], if it works, it works, if it doesn’t, nothing too bad can happen…right?”, grimacing while I winced. He continued buying T off his friend for a couple more months, before eventually ordering his own online.

Medical opinion is unequivocal: DIY HRT can be extraordinarily dangerous. To better understand this, I spoke with Dr. Lakshmi Ganapathi, a Singaporean doctor who studied and trained here, and is now a practising paediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital, the first centre in the U.S. to establish a gender multi-speciality service for children and youth.

She laid out the risks for me over email: potential interactions with existing health conditions, especially unknown ones; counterfeit or poor-quality drugs; difficulties with establishing potency; inappropriate dosages; and risks associated with injection, all compounded by the lack of professional supervision.

“Patients receiving HRT need careful titration of doses that balances many factors, as well as short- and long-term monitoring of risks,” she said. “They need to have the opportunity to discuss it with a trained provider who can be vigilant about risks and guide their overall care.”

Dacre and Amelia found this out the hard way. When they eventually went for blood tests at the insistence of their parents, who had found out they were self-medicating, the results showed they’d been overdosing. Their testosterone and estrogen levels, respectively, were off the charts.

While trans advocacy and support groups generally do not condone DIY HRT—TransgenderSG, for example, ‘strongly cautions’ against the practice—they nonetheless understand why individuals might feel driven to it.

First, the lengths to which Audrey, Amelia, Dacre, and many other trans people go to obtain HRT need to be understood against the dangers of untreated gender dysphoria. Multiple studies have shown that without appropriate and timely treatment, trans- and gender-non-confirming individuals are at much higher risk of depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide. Against these, like in Audrey’s case, experimenting with treatments can start to seem like an acceptable gamble.

While trans-affirming healthcare, including HRT, is available in Singapore under both the public and private systems, many trans people face difficulties accessing it, both as a result of structural and technical reasons as well as stigma and discrimination.

According to Leow Yangfa and Alexander Teh, two representatives from Oogachaga I spoke with, trans people of all ages and backgrounds have been known to attempt DIY HRT. However, a significant push factor here, especially amongst younger trans people, are the age restrictions controlling access to HRT. In Singapore, it is generally not available to anyone under 17, and between the ages of 18 to 21, both parents’ consent is needed to obtain it.

The basic rationale behind age restrictions is straightforward: to ensure patients can give informed consent to medical treatment.

In medicine and law, competence is well-established as a fluid and multifactorial concept, where age is neither the sole nor primary determinant. That said, because there is no singular and reliable way of applying this, many countries still default to age-based thresholds in practice. (In Singapore, this is generally 21.)

Nonetheless, according to Dr. Ganapathi, professional paediatric bodies do recognise that most adolescents develop the capacity to provide informed consent by age 16. One test for assessing this, known as Gillick competence, is used by doctors in specific circumstances, and has generally been accepted in Singapore.

Within the field of transgender healthcare especially, it gets very complicated very fast.

A trans teenager may have been certain of their gender identity from an early age, but may not necessarily be able to appreciate all the effects and risks of starting HRT, such as fertility loss. Because the treatment can induce permanent physical changes, it needs to be carefully considered. At the same time, starting it late—even after 18—can make socially transitioning harder.

Timely intervention can also help reduce the risk of adverse mental health outcomes, especially the trauma of puberty-induced gender dysphoria. Naturally, many trans teenagers are keen to start HRT as early as possible, but this brings us back to whether they can give informed consent in the first place.

In any regard, stressed Dr. Ganapathi, “each teenager’s capacity to consent, particularly for partially irreversible treatments like HRT, needs to be assessed individually.”

All three of my interviewees admitted (often, with some embarrassment) that, in their desperation, they had taken more risks than was probably wise. Audrey, for example, reflected that she had been “pretty cavalier” in hindsight.

“I just read what I could and took the lowest dose possible, and adjusted my dose based on the changes I observed in my body,” she said.

While DIY HRT dramatically improved Dacre’s mental health and quality of life, he struggled to come to terms with some of its effects, which he only learned about after seeing a doctor.

While he didn’t regret it, “you really need to think carefully before starting, because you can’t take these things back,” he wrote in a follow-up text. “I actually grieved about not being able to have kids [when I found out]. It really tore me from the inside.”

While there is no one-size-fits-all test for informed consent, the dual-parent requirement also bears scrutiny. It’s easy to see how this can be onerous for many people looking to start HRT—not just those who come from single-parent households, or ones whose parents don’t get along, but those whose families may be unsupportive, uninformed, or hostile towards their child’s gender identity.

For Dacre, Audrey, and Amelia, knowing their parents were unlikely to consent was what drove them to DIY HRT in the first place. (For that matter, none of them felt they would have come out to their parents, had they not been discovered self-medicating.)

“I understand that parental consent is to ensure that children are acting in their best interests, but in the context of Singapore, where so many parents are transphobic or uninformed, involving parents can sometimes erect a barrier between the child and their treatment,” said Audrey. “I don’t think denying, effectively, a child access to potentially life-saving treatment can be in their best interests anyway.”

In Singapore, according to Dr. Ganapathi, several medical procedures (e.g. sedation) only require one parent’s consent. “Given the legal precedent for one parent to consent in many other situations, and the many challenges patients may face in getting both parents’ consent, medical practitioners need to develop broader consent frameworks with the input of the legal fraternity,” she said.

Another consideration is puberty blockers, which are not currently available in Singapore. The treatment, which is provided to transgender pre-teens in many countries, works by suppressing the onset of puberty and halting the development of secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast growth and facial changes. Significantly, their effects are fully reversible, which makes them a compelling precursor to HRT.

While medical opinion largely backs their use (with appropriate assessment and parental consent), the long-term effects of puberty blockers are not fully understood, such as on bone density. Last December, in a controversial decision, the UK High Court ruled that under-16s would be unlikely to give informed consent to their use, which is also being walked back in Sweden and several US states. (I wrote to the Health Sciences Authority and Ministry of Health to seek comment about their stance on puberty blockers, but did not receive a response in time for publication.)

Nonetheless, between the unavailability of puberty blockers here and the challenges of obtaining HRT before age 21, there is a very real risk of trans teenagers facing harm either way: potentially going without treatment, or resorting to self-medicating.

Dr. Ganapathi opined that while puberty blockers—like any other medical treatment—need to be carefully studied, opposition to their use is often grounded in misinformation or implicit bias.

“Often, you get people saying that all this is happening because of the media or Western influence, stuff like that,” she said. “While there is greater awareness of trans issues and therapies now, thanks to the Internet, people’s positions on puberty blockers and trans healthcare tend to be rooted in their fundamental beliefs about gender.”

She pointed out that puberty blockers have also been used—to much less violent objection— in contexts outside gender dysphoria treatment, such as in children who begin puberty too early. (HRT, too, is prescribed in contexts outside gender transitioning.)

“If people recoil against these in the context of trans kids specifically, it’s possible that their real concerns don’t have to do with the medication or its safety profile, but the purpose it’s being used for,” she said.

In this, age restrictions are only one aspect of a larger problem. Although access to trans-affirming healthcare has improved over the years, many significant systemic barriers remain.

As a starting point, it must be noted that unlike many other countries, HRT is relatively affordable in Singapore. Under the public healthcare system, both HRT and related consultations are available to Singaporeans and PRs at subsidised rates. From what I could ascertain, these are not prohibitive: a vial of T costs around $15-20 and lasts several weeks, while a month’s supply of feminising treatments costs around $30-$60. (Both the medication and consultations, naturally, cost much more in the private sector.)

Of much greater concern are bottlenecks in the system: long wait times, coupled with a lack of providers who are both medically and culturally equipped to provide trans-affirming care.

At present, the main clinic providing transgender healthcare services is the Gender Health Clinic at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH). When it opened in 2017, it was the only clinic in the public healthcare system believed to specialise in gender dysphoria. Its predecessor, NUH’s Gender Identity Clinic, closed for good in 2008, leaving a nearly decade-long gap.

While reviews of the quality of care at IMH’s clinic have been uniformly positive—both from trans people I interviewed for this story and others, as well as online accounts—a common grouse is that wait times for an appointment can be as much as 2-3 months, if not more. This increases the likelihood that patients, desperate for help, might turn to DIY HRT in the meantime.

To the best of my knowledge, the IMH clinic is staffed by only two doctors, one who sees under-18s and one who sees adult patients. Meanwhile, according to Dacre and Amelia, COVID-19 has made the wait for a slot even longer.

More recently, however, at least one other public hospital—Changi General Hospital—appears to have opened a gender dysphoria clinic.

“There are clear resource bottlenecks, and at the same time, we do know that transphobia exists in the healthcare system, as it does in society generally,” said Yangfa, the Executive Director of Oogachaga.

He speculated that problems may also lie upstream, with a lack of doctors who are trained to provide trans-affirming care. “It may well be circular, for example, psychiatrists who can’t diagnose GD (gender dysphoria) because they’ve never learned about this or seen a case. If you don’t see, you don’t know.” While the issue of gaps in medical education is not unique to Singapore, it merits dedicated attention and commitment to solving.

Either way, he added, “the need is clearly presenting itself, so insufficient demand cannot be cited as a reason. Trans people need to be treated equally, and trans healthcare, like access to healthcare for anyone, is a human right.”

Thorny as the debates around consent, puberty blockers, and HRT may be, they can all be linked to a common structural challenge: massively inadequate access to information around gender identity issues here.

DIY HRT, after all, is only one example of how this knowledge gap works against trans people’s interests. While the Internet has helped increase awareness about gender identity issues (and enabled trans people to connect and seek support), this has been accompanied by a flood of misinformation, some unintended and some malicious. (Dacre, Audrey, and Amelia all shared that their families had sent them false information about HRT and trans-ness at some point.)

In this climate, when legitimate concerns about under-studied treatments can bump up against blatant lies and fear-mongering, the need for reliable information is not only critical, but urgent. Arguably, the single biggest step toward improving trans healthcare in Singapore—and possibly one of the simplest—would be to ensure trans people, especially youths, can easily obtain the information they need to make informed decisions about their own lives.

I remarked to Yangfa and Alexander that researching this article, from combing the Internet for resources and piecing together information from word-of-mouth, felt like it’d given me a small taste of what the process might be like for trans people considering HRT.

Even without the personal stakes, it felt like I was preparing a dissertation on a topic I’d never studied, ploughing through incomprehensible medical literature at times, falling down Reddit rabbit holes at others. An off-hand comment Amelia had made during our interview came to mind: “Your best friend is the Internet, and other people who’ve gone through the same thing.”

“The knowledge barrier is very, very real,” said Yangfa. “It takes so much effort to find out everything, especially if you are not connected to the community.”

In Singapore, MOH does not publish public guidance about gender dysphoria, although this is available for many other conditions (the entry for HRT only addresses it in contexts outside gender transitioning). Similar guides, for example, are published by the health authorities in the UK and Australia. At present, the most comprehensive local guide is maintained by TransgenderSG, an NGO.

Remarkably, even the two specialist gender clinics in the public healthcare system—at IMH and CGH—are not clearly advertised or signposted on the hospitals’ websites, and are most easily found by a direct Google search.

Better access to information would do wonders not just for trans people, but their families, too. Yangfa, Alexander, and Dr. Ganapathi were all adamant that holistic trans-affirming care takes a village. Beyond a broader suite of services (psychosocial support and speech therapy, for example), medical social workers are often needed to counsel patients’ families, especially where they are unsupportive or ill-informed about gender dysphoria.

“Family-centred care is so, so important. Parents need the resources to be able to support their kids,” said Dr. Ganapathi. “And they have a right to information too, be it about therapies or service providers.”

While Audrey, Dacre, and Amelia don’t regret DIYing per se, they all felt they would have benefitted from advice and oversight. If anything, having had time to reflect on their choices has made them reluctant to encourage others to do the same.

“Do I feel DIY HRT was worth it? Yes,” said Dacre. “It helped me through a very dark period of my life, becoming who I really was. But I wouldn’t tell people ‘go do it’, because it’s extremely dangerous.”

Audrey, the only one of my interviewees to have never sought medical supervision, continues to DIY, taking as low a dose as possible to avoid alerting her parents. While she hopes to get an official prescription eventually, she is resigned to lying low till she turns 21.

“I guess one thing that stands out to me is the loneliness of the whole affair,” she texted me a couple of hours after our interview. “Medically transitioning should have been an exciting process where I get to celebrate who I really am, but instead I have to hide the changes and what I’m doing every day, and that’s disconcerting.”

“Perhaps coming from an unsupportive household compounds it, but I’m really doing this thing on my own without anyone to look out for me or monitor my safety, and it’s scary knowing that no-one’s taking care of me.”

Resources for transgender individuals: