It’s Hari Raya, a time of celebration and, of course, house visiting. Every year without fail I visit my aunt on my father’s side. I feel particularly at home in her house but not for reasons I would like such as because she’s family or because of memories I had there. The familiarity partially is because of that, of course, but it’s mostly something else. My family sits down on the couch, which actually used to be ours from moving 2 houses ago. Her TV too was once ours, we decided to replace it because it was too old. I guess it wasn’t too old to her. Below it is an old-fashioned sound system, also ours. In fact the whole set up complete with the rack the set-top box rests in was ours. Her coffee table too.

In some ways, I’ve lived in my auntie’s house longer than she has. My cousin would come running out of his room which he shares with 2 other siblings. He wears what I recognise as my old Hari Raya outfit from a few years ago. I get the same sense when I visit my other relatives and recognise my old furniture breathing life anew in their houses. As a kid it made me wonder why we never got things from our relatives and why we could always move so often but my aunts and uncles never seemed to budge from their HDBs. Mostly, I wondered why the stuff we considered old, outdated or rubbish was stuff my other relatives would want.

Now, I preface this article with the caveat that I am aware the problems I’m about to discuss are privileged ones. This article is the equivalent of me wiping my tears with money. Well, I don’t literally do that, but I might as well.

I will say, however, that any who judge you by your privilege is just as bad as any who judge the impoverished for being impoverished. To say that a problem is invalid because you can smell hints of upper class and therefore deem it inherently invalid is moral relativism and in general moral relativism stinks doo doo. Now without further ado do, let me hit the woes (I’m coining this term, I will publish more under my ‘sad Tiktoker’ sticker pack).

I’m not the quintessential Malay, at least according to popular imagination. I, and most people I know, would regard my extended family as closer to that.

My mom is a senior banker, and it’s the same job she’s had since before I was born. My dad is currently retired and my mom earns more than enough for the whole family, but when I was younger, my father used to have a high-ranking job in a shipping company, which was when my family had the most money.

I don’t know much more than that because my parents never spoke to me or my sister much about work or the development of their careers. The fact that they were always able to hide that speaks to the stability of their jobs and the lack of financial stress we had. My family is far removed from the typical Malay household. Before I was born, my dad used to be a crewman on shipping vessels. Working with an international crew and sailing across the world for the majority of his time must have done something to broaden his world view, and so I regard my father as a globalised man. I remember growing up family conversations skewed towards the cultures and politics of other nations as often as it did towards those of our own. This sets the backdrop for me as a person and why I am who I am today.

I tend to label myself the least Malay Malay there is in that I barely tick off any stereotype boxes. I don’t play soccer, I do well in school; I don’t, in fact, speak Malay well at all and the list goes on. It’s just a joke I use, mostly because these stereotypes aren’t completely true anyway (obviously). But they’re only mostly untrue, factually, not socially. As Paul Simon sang, “he doesn’t speak the language, he holds no currency”. My lingua franca has always been English, and pretty much only exclusively so—the fact that I use the phrase ‘lingua franca’ can attest to this. It’s the language I speak to my family and all my friends, and I do mean all my friends including the few interactions I have with Malay people outside my family. Some people who are bad at their mother tongue say they can’t speak it but they can at least understand a conversation if they heard one. I can’t. Sure, I know words and I can string a coherent sentence or two, but to say I can functionally use the language in any form is objectively wrong.

Have I mentioned that I’m not close to my extended family?

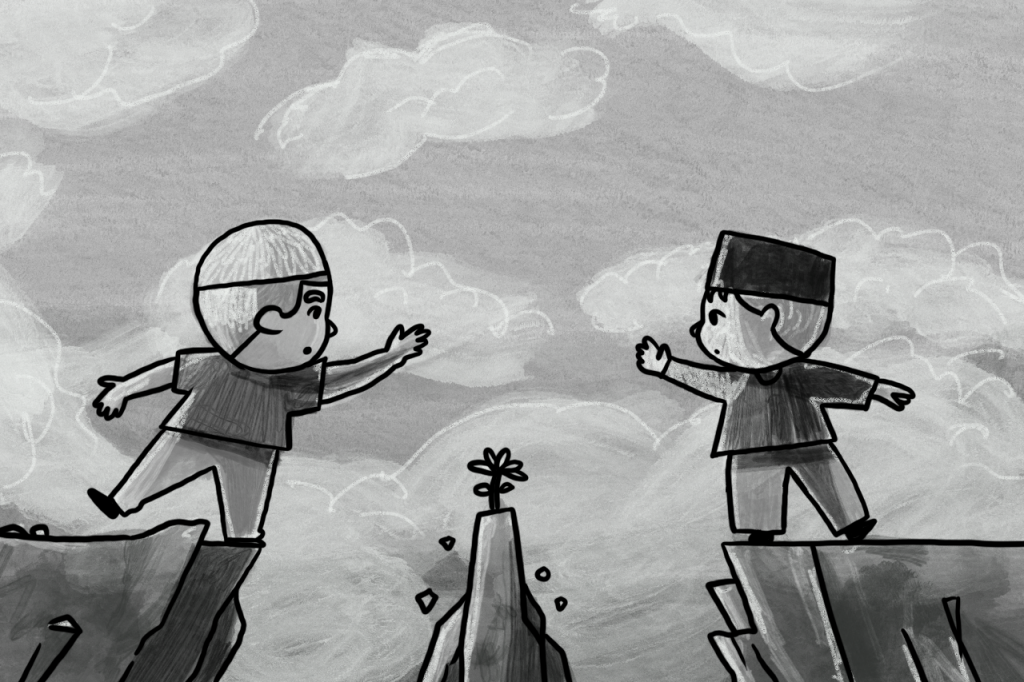

Well, I’m not. One stereotype box I do tick is that I have a big extended family. On my Dad’s side alone I have 20+ cousins stemming from 5-6 uncles. Like Yin and Yang, during family gatherings my cousins and I fill opposite roles of the congeniality spectrum. For every pleasant conversation my cousins have about where they’re studying or something else, I scroll through 10 minutes worth of Reddit posts. For every baby that gets passed around between them like a puppy at a primary school, I sit in the corner fascinated by a funny thought I just had.

I’m not one of them, although that’s not to say I have disdain for them.

I was at the market with my mom when she bought some vegetables from this Chinese lady who called it by its Malay name. Out of curiosity, I asked what it was in English, and the lady told me. As we were walking away she asked about our nationality. She guessed that we were Burmese, then Filipino, then Indonesian. After a pause my mother replied, “No, we’re Malay.” The Chinese lady responded, “Then why did you ask for it in English?”

The first barrier between my cousins and I is the language. I feel so uncomfortable and foreign speaking what is supposed to be my language. And maybe it’s only right that I feel this way. I never spoke it colloquially, I never watched many shows with it, and I don’t ever think in Malay. As far as I’m concerned, Malay is to me as it is to a Chinese person, just something vaguely mixed in me because Singapore is a Rojak society and you’re bound to learn Malay by happenstance.

My extended family treats English with the same alien attitude, as if the Anglo-Saxon world is so far removed from theirs and it’s never something they can identify with. Again, perhaps only rightfully so.

When I answer their questions in English, and I mean grammatically correct, no-Malay-accent English, I think they see me as arrogant, like I can’t stoop down to their level to speak ‘normally’. I wish me speaking in English and them in Malay and both of us understanding each other would work. But it doesn’t. It’s like I’m not one of them.

I feel great shame that I can’t functionally speak Malay. This isn’t not for lack of trying, it’s for lack of nurturing. Let’s face it, it’s impossible to ingrain a language in you if you never speak it at home. So I don’t blame myself, although nonetheless there is a sense of shame in that it’s an identity I’ve lost. Sure, my English totally rocks (I think), but I feel bad for the thousands of Malays who only ever get functionally good in Malay and get left behind by an education system that operates in a language they can’t understand. I’m thankful that never happened to me. I’m thankful that the majority of the internet that contains all the information I could ever want to know is in English, allowing me to comprehend and learn with ease. I’m thankful I’ve connected with friends and strangers so different from me because the lingua franca of the world is the one I happen to use. In that sense English is the biggest bubble breaker for me, and conversely it’s what traps others in their own.

But my cards aren’t gained, they’re swapped. Every Chinese friend I make is a family member ostracised. Ever article read, a conversation with a family member I won’t be having. Bukan seerti-seiras. It’s not commensurate.

Hassan Minhaj in his standup talks about paying the immigrant tax as an Indian in America. I can’t help but think I’m partaking in the same fees. Oh you want to appreciate English literature? That’ll cost you appreciating Malaysian and Indonesian cinema, a cinema that all my relatives relate to. You want to get an A1 in O’ level English? Take this B4 for Malay. You may argue that they’re not mutually exclusive, and I would agree that it isn’t for a lot of people. But it was for me.

I question why cultural identity is so important because morally and practically speaking, losing your mother tongue is no harm, no foul. But it does tie you to belong somewhere. You can watch Malay shows feeling they cater to you, talk to Malay people recognising the same speech patterns and slang you know, and bond with a family whom you regard as familiar. Some days I feel I come home to a house and not a home, like I felt a stronger sense of belonging in school or wherever I was before I walked through my front door.

It begs the question, whether all this time the onus was actually on me to become ‘more’ Malay.

After buying what we wanted, my mom came home and set to work cooking in our open-air kitchen. She laid the ingredients out on the single-slab marble countertop, and began cooking.

I imagine that every day thousands of Malay mothers like her set up their kitchen just the same, albeit in a different space with different decor. Meanwhile, I sat down on our sofa and watched movies in our living room, which is connected to a balcony with an unobstructed view, something we paid extra for when buying our house. I imagine many boys do the same when their mothers cook, just on smaller TVs and on less decadent couches.

Come Hari Raya, the yearly visits always make me wonder. At their HDB flats, I get served simple fizzy drinks and watch a small plasma TV. Sometimes they’ll have a stand-up fan in the corner of the room, and other times their ceiling fans won’t work, caked in dust.

Some houses can’t fit all of us so we sit on the floor, other houses have toilets with the default tiling that all HDB flat toilets have, and they’d have lots of colourful pails for scooping water. I wonder, for the relatives who call this home, what they must think when they enter my spacious, fully-renovated and air-conditioned living room with wooden floors. What do they think when my parents bring out a pristine china set to serve expensive tea as they watch shows using our Netflix subscription on a big, 3D-ready borderless TV hung on a custom-built rack? What do they think leaning over our large balcony or using our toilets with bespoke glass doors and marble and ceramic detailing?

Do they think we live in the same world as them? Do they regard my house as a Malay household? Do they think that the way I act starts to make sense?

Because when I go to their house and I eat their food on their Ikea dining table, I think: I can’t pretend that we are as similar as families are supposed to be. I have more in common with my German neighbour who moved here than with my own aunties and uncles.

I feel uncomfortable sitting in the homes of my relatives because they know I’m used to amenities they could never provide me. I see it in their faces when they serve me food on plastic plates. I see it when they switch to Suria on their desktop-mounted TVs for me. I see it when we talk to each other like there’s an impossible chasm we can’t bridge.

As a meritocracy, Singapore is indoctrinated with the mantra that SES doesn’t matter. I don’t want to contend on how it might affect one’s future but to say that it doesn’t affect us at all is naive to say the least. The poor make friends with the poor and the rich make friends with the rich. I too make friends with people roughly as well to do as I am. This is not a product of discrimination as much as it is a byproduct of our SES. If you’re richer, you’re more likely to have parents with a higher education, which gives you an advantage during your early education and you get into a good secondary school. And the people there, who make friends with each other, tend to be from the same well-off backgrounds.

After a few English movies filled with violence that Islam would disapprove of, morals we don’t share, and characters living lifestyles I never did, my mom was finished cooking. She had made a traditional Malay dish, something she said we used to eat as kids when grandma was still healthy enough to cook for us, although I seem to have no memory of it. I ate and realised that it was something I had not tasted in years. I then went on to call it by its English name, having Googled it out of curiosity. This was the name I would use when I texted my friends about it, about how new an experience it was to me. Friends who would find it just as alien as I did.

The third and final barrier is upbringing. SES affects more than just my material possessions, and therefore my upbringing. I grew up in an upper-middle class home. My parents are educated, my dad could help do my homework when I was a kid, and has a good command of academic subjects. Growing up, I consumed Western media on TV and on the DVDs we could afford to rent weekly. I listened to Western music and learnt Western ideas, ones my father himself would learn from his job as a crewman.

My family never had conversations concerning budgets or really, the lack of anything. Rather, we entertained concerns about what destination to fly to at the end of the year, and when we should move. I grew up in excess. I did well in school and I went to the best ones and sat in the top classes. I rarely ever spoke to Malays in my classes because I could count the number of Malays I saw in my schools on one hand. I went to an expensive specialised Secondary school and I did well for my O’ levels. I got the freedom of choice—despite my grades qualifying me to get into the best JCs—to pursue filmmaking in polytechnic where I mixed with even less Malays in my classes. Yes that was a major flex, but it serves a point, a non-flexing point.

I don’t know what it was about the choices I made during my education, but I never seemed to go where Malays go, if ever there even was a typical path for us. Inevitably I mixed with Chinese kids much more, upper-class Chinese kids to be exact. I learnt more about Christianity which the majority of my friends subscribe to than my own religion just because people around me would bring it up more often. I talked the way they do, inculcated the same habits in eating, hobbies, and thinking as they do, and hell I identified with the same sphere of cultures as they do.

But I wasn’t one of them. I can’t count the number of hours I’ve sat bored and miserable in my room on CNY because my entire circle of friends disappear to their families, as they should. So many times I’ve had FOMO seeing all my friends going out together during Hari Raya when I’m busy not talking to my extended family. I can’t celebrate their Christmas or go to their churches or go drinking with them as they so normally do. Not that I was influenced by their religion, but it felt so natural being with them to go where they go and do as they do.

When in Rome, right? But that’s not me. I’m born different. This is no Boy-In-Striped-Pyjamas-fence situation, but it is a divide based solely on my race.

I don’t think my parents would be comfortable knowing how fully ‘Chinesed’ I am. Don’t you think your parents not being comfortable with your identity rings too many bells from too many gay movies?

I don’t go home to a family where I suddenly belong again. My extended family never grew up with that ‘only Malay kid in class’ starter pack. I can’t talk to them about the things I normally think about: the shows I watch, hobbies I partake in, issues I care about or facts or news I just learnt. The cultural sphere that encircles every one of my extended family members shares no overlap with mine. None. It’s a Venn Diagram with no common middle, a mathematical concept which I have actually tried to bring up in conversation with abysmal results.

In all this, I haven’t really mentioned my sister, who I’m sure suffers the same to a certain extent. She went to good schools, grew up the exact same way I did, and has the same troubles with our cousins. But some days I see her bring home Malay friends and I wonder how she does it.

How did she retain that part of her while forging a path so off-tangent from the typical Malay? Our President is Mdm Halimah Yacob. Hell if there isn’t a more Malay looking woman out there. When I see her or Dr Yaacob Ibrahim, the Minister for Muslim affairs, I wonder if they face the same issues. Do they wonder whether Makciks are meant to be President? On their off-days do they visit relatives who don’t understand them too? And do those relatives regard them as foreign?

If so, they never mention it. I guess I don’t either. It begs the question whether all this time the onus was actually on me to become more Malay.

In the end, this is not to say that my race is defined so narrowly by class or by language. I’m Malay, it is what it is.

But with the label ‘Malay’ comes averages. The average malay is an amalgamation of certain parameters like wealth, education level, and affinity to soccer. The perfect average Malay would fall in the middle of all those bell curves. But if you adjust those parameters too far to either side of the bell curve, he’s still Malay, although he might as well not be. I just so happen to be a Malay whose parameters got shifted to the ‘upper class Chinese’ setting evidenced by the fact that that’s the setting all my friends are on. I prefaced this article by saying it was about a privileged problem, but that’s only as it applies to me.

As often as I have problems connecting with my relatives, I also see my uncles on the other end of the financial spectrum struggling to connect too. It’s not a privileged problem as it is a difference problem faced by anyone who deviates too far from the centre.

I went to a radio station for an internship, where I got to do my own radio show. During the 3 months I was on air, unbeknownst to me, my mother shared my shows with the rest of my extended family. It’s funny to think they heard more from me and learnt more about me through that little video camera live streaming my shows than they will probably ever hear from me in real life.

Halfway through that internship, I remember visiting my relatives for Hari Raya. My Dad showed a clip of me energetically back-selling a song on air. Back-selling a song refers to when a DJ announces the artist and title of a song after it has played. My auntie, who I’m sure could count on her hands the number of words I’ve spoken to her, said, “Oh my god! He has a voice after all!”

She said ‘he’ instead of ‘you’ because she was speaking to my dad, not to me. In her mind, she knew she wasn’t going to get an interaction from me. It’s interesting watching them talk about me in third person while I’m right there. So who was I on air; that person who was so free to talk?

The answer is: I was me. Rid of all the judging eyes and the guilt and the pulling and pushing of different identities, I spoke freely.

Then, who am I? In The Green Book, the protagonist who struggles with his identity screams, “If I’m not black enough and I’m not white enough and I’m not man enough, then tell me Tony, what the hell am I?”

Sometimes, I guess far too often, I too ask myself, “So if I’m not poor enough, and if I’m not Malay enough, and if I’m not Chinese enough, then what do I call home?”

Because that’s what it boils down to in the end. That’s why it matters to me. Having people I call home. Not just in the sense of family and not just in the sense of a nation. But in the sense of a community that makes me feel like we all grew up the same. That I think thoughts and experience life the same as some people.

I have friends, sure. But I don’t go home to friends. I don’t sleep underneath the same roof as friends, and friends aren’t the ones the hospital calls if I’m about to die. Being individualistic is fantastic and I applaud the people who strive for it. But you must admit that being yourself can only be done by yourself. It gets all too lonely all too quickly.