Top image credit: Still from footage of a multi-ministry press conference on the Wuhan coronavirus, Channel NewsAsia (Jan 27th)

Trying to contain rumours that are already making the rounds is essentially responsive in nature. But Minister Chan’s comments acknowledge that there is value in being proactive and forthcoming from the start.

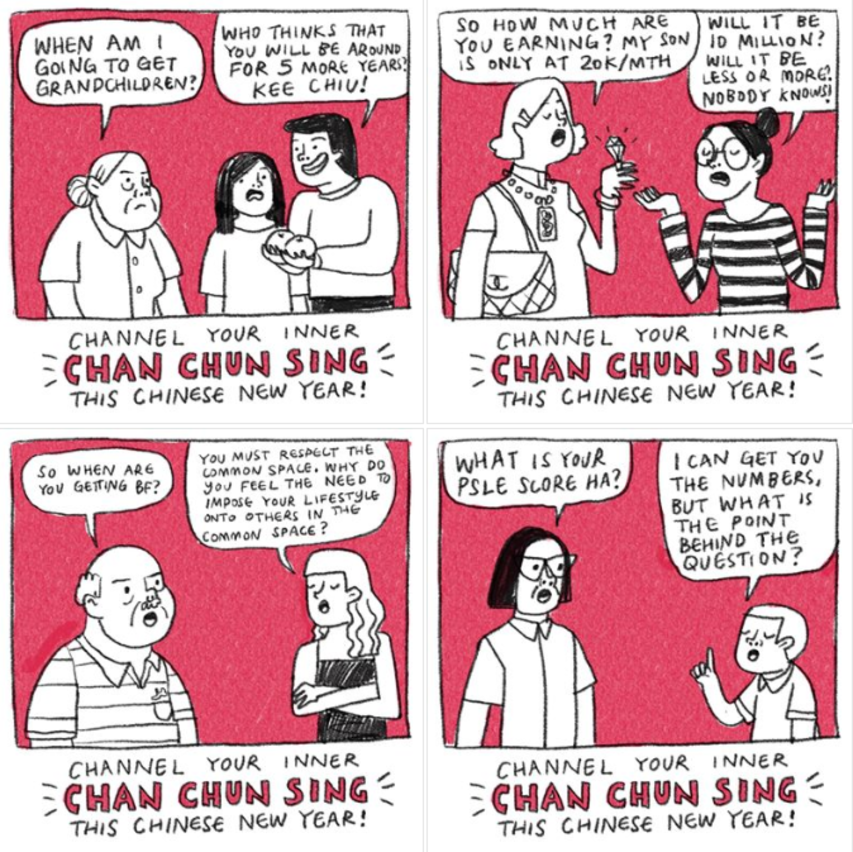

This is quite a different tune from the one he was singing a couple of weeks ago, when he met MP Pritam Singh’s questions about Singapore’s workforce with the now-infamous, “What is the point of the question?”

A few recent examples: when POFMA was being debated in Parliament last year, Minister K Shanmugam rejected MP Louis Ng and NMP Irene Quay’s calls for a Freedom of Information Act. His reasons? Civil servants would be “inundated’”with “odd requests”, and such an Act would mainly benefit lawyers, businessmen, and journalists (never mind that it’s our job to ask questions).

And on January 20th, in a speech at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) conference, Minister Chan (yes, him again) audaciously declared that sharing data “will not be a panacea to policy issues”.

He then followed up with this gem:

“If people don’t trust you, you can give as much data as you want, and you will not win over the hearts or the minds of the people.”

I’m sorry, but this is absolutely bonkers.

Saying that people’s trust is a prerequisite for releasing information is completely backwards. Being forthcoming with information is what creates trust. It is the ultimate gesture of transparency from a government which understands that a vice grip on information doesn’t guarantee control. It only gives the impression of having something to hide.

A public health crisis like the Wuhan virus outbreak shows how an open, communicative government is critical to maintaining public confidence. When authorities insist on withholding information, they effectively cede control of the narrative. And in the absence of clear direction, people will automatically assume the worst.

When the virus was first detected in Wuhan, public health officials claimed that the illness posed little danger. According to the Guardian, the official line from China’s national health commission was that the situation was “controllable”.

Before you could so much as sneeze, hundreds of people were sick. Wuhan went into lockdown. People started speculating that millions had ‘fled’ the city ahead of time, though nobody knew for sure (or if it was just Chinese New Year travel). ‘Whistleblower’ videos began circulating on Weibo and WhatsApp, purportedly showing bodies lying on gurneys in Chinese hospitals and ‘nurses’ claiming the body count was being wildly under-declared.

It’s possible that some of the rumours were trolls at work. It’s also possible that some of them stemmed from ordinary people, badly spooked, who had resorted to filling information gaps with guesswork.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) has been providing regular updates about suspected and/or confirmed cases, including contact tracing. News about travel restrictions, quarantine sites, mandatory leaves of absence for returning travellers, and enhanced screening and checks appears daily. Ministers have taken pains to appear on the ground, and reassure the public that robust measures are in place to manage the situation.

All this goes to show that being forthright goes a long way towards maintaining people’s trust.

This point stands whether or not there is an ongoing crisis. An emergency like the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak makes the need for transparency more obvious, but how an organisation responds in an emergency is only as good as its practices on an average day.

If leaders are already cagey and defensive in the best of times, or don’t trust their people to act sensibly, this probably won’t change during the worst.

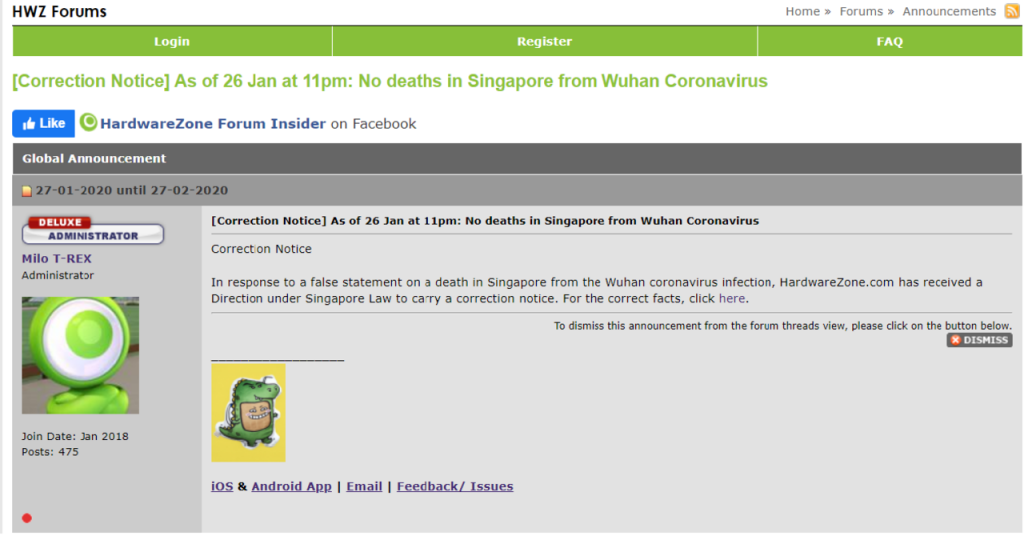

The post was made at 5:50 PM on Sunday, January 26th. What followed was swift and painless: the POFMA office issued a Correction Notice that night, and SPH Magazines complied by Monday morning. The post was taken down and a correction posted in its stead.

This was the sixth time POFMA was invoked since it came into force late last year. We can argue over whether the first five cases were ham-fisted bids to stifle political dissent, or good-faith attempts to combat disinformation.

In this case, it was clear that MOH had good cause to act without delay. Exploiting people’s fears to stir panic in a crisis is utterly reprehensible.

But a further point to be drawn from all this is that resistance to releasing information creates the perfect kind of breeding ground for rumours, conspiracy theories, and yes, fake news, that POFMA was meant to combat.

Tackling fake news becomes even more challenging when there is a fundamental imbalance in access to information. Disinformation spread by malicious actors is one thing, but speculation born of ignorance is another.

As NMP Walter Theseira pointed out during the Second Reading of POFMA in Parliament, differences in opinion are bound to arise when the public only has partial information. If only the government has the full picture, then it shouldn’t be affronted when people try to fill the holes with guesswork.

Of course some people will approach data with a confirmation bias (as Minister Chan raised in rebuttal at the IPS conference). Of course others will use it to prod the government with uncomfortable questions.

But the former’s blind spots will speak for themselves, and the latter is what engaged citizens are supposed to do. You can’t cherry-pick when it comes to active citizenship. If our politicians want Singaporeans to be clear-eyed, digitally literate, and actively invested in this country’s future, then they need to give us the information we need to know what we’re doing.

The reality of our world now is that social media will always be flooded with fake news. Even the most liberal use of POFMA (god forbid) would be like holding up a Band-Aid to a tidal wave.

And if—as I’m sure the government would agree—we all have an interest in distinguishing fact from fiction, then it should be more upfront in giving us the data to tell the difference.