All photography by Zachary Tang.

As we stepped outside Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan that Wednesday afternoon, I asked RICE’s photographer Zach, whose father’s side of the family is Teochew, whether he ever thought about joining a clan association.

“Nah, I’m just too busy at the moment,” Zach replied. “I do speak some broken Teochew at home with my grandparents. But joining a clan is just not a priority for me right now.”

The same sentiments were echoed by the rest of my Chinese-Singaporean colleagues, whose ancestors hail from various Southern provinces in China: from Hainan to Jiangsu and Shanghai.

This is the unfortunate reality for many young Chinese Singaporeans. Outside of daily interactions with their Chinese grandparents, who may still have memories of the old country, the closest they ever get to experiencing their Chinese roots is at the family meal table over food.

To better understand this important part of Singapore’s heritage, I set out to learn about the role that clan associations played in Singapore’s early history.

Why Were Clan Associations Formed?

The origins of clan associations (or 会馆, ‘huay kuan’ in Chinese) can be traced back to the early 1800s.

In 1819, the founding of Singapore as a British colony prompted the arrival of coolie labourers to support a burgeoning merchant class. Many of these labourers arrived penniless and alone, leaving their families behind in China in order to earn a living.

Clan associations were formed, at least in part, to address these challenges and provide a support network for its members. As the various Chinese communities in Singapore grew, the clans started pooling funds to take care of their own, buying land to build temples and securing burial plots. They also facilitated personal and business introductions between members, while establishing links back to their home provinces in China.

This legacy of business and land ownership among the clans also contributed greatly to the development of modern-day Singapore. For example, Lim Nee Soon, a Teochew merchant, was Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan’s founding president. He helped to develop Singapore’s Northern heartland that would go on to bear his name ‘Nee Soon’, until it was later renamed to its pinyin spelling of Yishun. Meanwhile, the Hokkien influence is responsible for the names of neighbourhoods like Ang Mo Kio, Toa Payoh, and even the pronunciation of Singapore itself (sin-ka-pho).

What Do Clan Associations Do Today?

Today, the role of the clan association has evolved from fulfilling basic social and community functions to higher order objectives of cultural education (eg. traditional opera and performance arts), preservation of regional dialects, and the establishment of business networks both within Singapore and across Asia.

To get insights on how these changes have affected their membership and operations, I interviewed the Presidents of the two largest clan associations in Singapore: the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan and the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan. Together, Hokkiens and Teochews make up about two-thirds of the ethnic Chinese population in Singapore.

In His Own Words: Mr Tan Cheng Gay, President of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (SHHK)

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, throughout its 180 years of establishment, has always focused on the three key areas: education, culture and social service.

Our membership in recent years is around 5,000 members.

Most of SHHK’s members are below the age of 45, although our oldest member is 103 years old. In the past, the occupations that have been associated with the Hokkien community include commodity trading, shipping and maritime, banking and property development. Now, our members come from all walks of life.

Most of our new members initially join our Huay Kuan to facilitate their children’s enrolment into one of the five SHHK affiliated primary schools – Tao Nan School, Ai Tong School, Chongfu School, Nan Chiau Primary School and Kong Hwa School – under Phase 2B of the primary one registration exercise.

Over time, many members developed a sense of belonging and camaraderie after becoming part of the SHHK family. Through cultural events and language classes that we host, they became more enthusiastic about the Huay Kuan’s cause of promoting Hokkien culture, and continued to volunteer their services at language classes and cultural events even after their children’s graduation.

The Hokkien culture, alongside other cultures, certainly left its imprint on local Singaporean culture. Many Hokkiens have upheld the spirit of endurance, hardworking, and the “can do” “never say die” attitudes of our forefathers. A common colloquial Hokkien term (爱拼才会赢 ai piah jia eh yia, translated literally as ‘you have to fight in order to win’ ), which by the way is also the title of a Hokkien song, aptly encapsulates the ‘never give up’ Hokkien spirit.

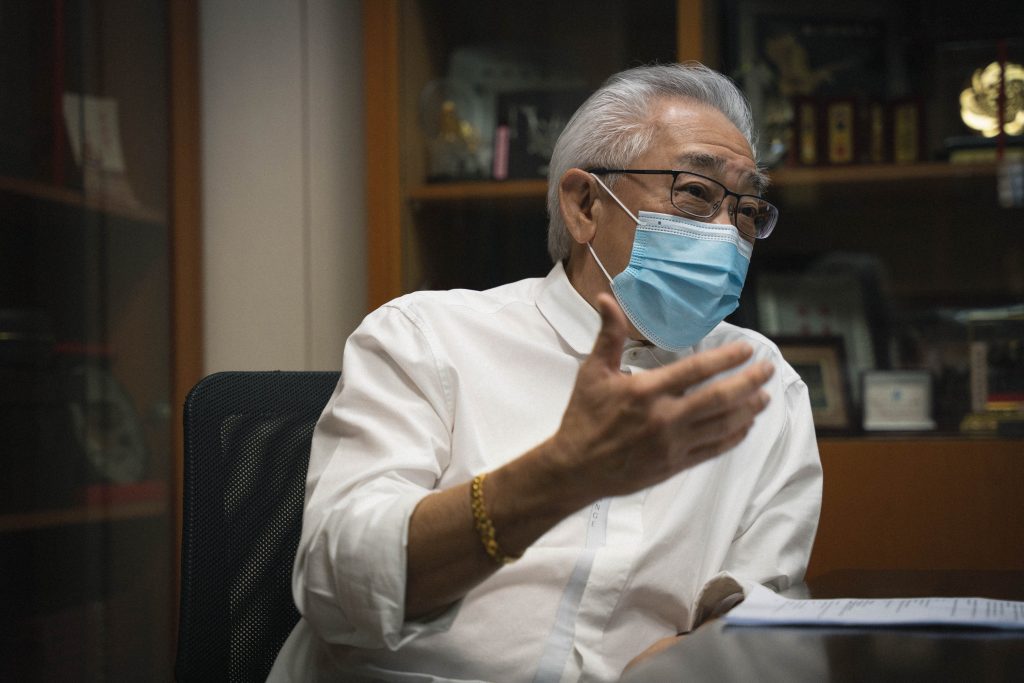

In His Own Words: Mr Chan Kian Kuan, President of Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan

In our late Minister Mentor’s book Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Ideas, LKY mentioned Teochew culture of entrepreneurship and resourcefulness as the X-factors that helped nations like Singapore succeed, noting the disproportionate number of Teochew ministers like Teo Chee Hean and Lim Hng Kiang.

Today, we have DPM Heng Swee Keat, a Teochew Singaporean who was a guest of honor at our Huay Kuan’s 90th birthday celebration in 2019, which took place in the Yishun heartland of our Huay Kuan’s founding President Lim Nee Soon.

As the second largest clan in Singapore, we have about 4,000 active members.

Our Huay Kuan fulfills three major roles:

1. To promote Teochew culture by holding Teochew language study groups and reviving interest in Teochew opera.

2. To support our Teochew Youth Group (Qin Nian Tuan). A programme that’s the first of its kind in Singapore that helps Teochew exchange students from China integrate better into Singapore’s community.

3. To promote business networking opportunities for Teochew entrepreneurs and businessmen. These regular networking sessions and business awards enable Teochew Singaporeans to connect with Teochews overseas.

The Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan is actually more famous outside of Singapore because we are the founding members of many Teochew chapters and associations within Southeast Asia. This is one of the reasons many people want to become members — to gain access to such a community. Of course, many Singaporeans also come because of genuine interest in the culture and language of Teochew.

How Are Clans Trying to Stay Relevant?

Clearly, the membership numbers in the two largest clan associations (5,000 for Hokkien, 4,000 for Teochew) fall well short of the size of their overall communities here in Singapore.

What explains this lack of interest? How can clan associations better appeal to a younger demographic? Is the Chinese-Singaporean identity even relevant to the current generation of Singaporeans?

Both Presidents believe so, although some reforms are necessary to better promote the benefits of membership to young people.

For starters, membership in many clans remains patrilineal, meaning that only those whose fathers are from the relevant backgrounds qualifies them for membership. This outdated aspect of their Constitutions is changing to include the mother’s side as well, in no small part due to the clan’s push to add younger, more engaged members.

They are also trying to modernise their outreach. The Hokkien Huay Kuan has developed a collection of Whatsapp emojis, featuring popular Hokkien phrases, to promote the use of Hokkien in our chat groups. The Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan holds youth events that feature performances by Teochew hip hop groups like AFinger (壹指團體).

As We Grow Older, Our Roots Become More Important

So despite all of these efforts, are clan associations becoming obsolete in Singapore?

According to two Huay Kuan Presidents, their clans’ steady membership and influx of curious Singaporeans suggests otherwise.

In fact, clan associations, rather than becoming obsolete, could become more relevant with time, as young Singaporeans grow older.

For example, Mr. Chan from Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan admitted that he himself didn’t become an active clan member until well into his middle age.

“When I was younger, I thought it was very bothersome when my family would drag me to these clan association events,” he recalled. “I wanted to work, make money and not have to deal with any of these responsibilities!”

But this all changed when he grew older and his father passed away.

“As you grow older, you start focusing less on studying and earning money. You start to value your family and roots. It is very important to our sense of belonging.”

This phenomenon is borne out in the membership numbers; most members either join or become active in their early 40s or 50s. This appears to be the natural course of things.

At the risk of sounding complacent, clan associations are betting on the fact that, as Singaporeans grow older, family and community will take up a more central role in their lives.

And Huay Kuans will still be there to welcome Chinese Singaporeans back into the fold.

Let us know what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.