All images by Li Ling

Young widowhood is often met with silence in Singapore—a private grief swept under the carpet because it’s too uncomfortable to bring up. But what if, instead of turning from it, we choose to face it with openness, gentleness, and grace?

For 41-year-old documentary photographer Li Ling, she chose to confront that heartache with acts of love and remembrance.

Through tender, everyday portraits, she chronicled her late husband’s journey with cancer in Metamorphosis and Home. The photographs became a way to honour his spirit—and a tangible legacy for their two young daughters to hold onto and feel close to their father.

For Li Ling, the impact of losing her late husband, Larry, went beyond those frames. It led her to connect with another young widow, Naadira Aziz, which eventually inspired her latest body of work. Still Here captures the quiet rituals of moving on: the sorting, the keeping, the letting go of objects left behind by loved ones.

Li Ling takes us through her work to share how she approaches the heaviness of loss with care and love through her lens.

Hi Li Ling, we first crossed paths while covering the SDP rally during GE2025. It was only later, through Instagram, that I discovered Metamorphosis. What moved you to begin documenting your late husband Larry’s journey with cancer?

We shared a love for photography, but I didn’t always document Larry’s 10-year journey with cancer. Between us, he was more intentional in documenting his cancer journey than I was, at times even directing me to pick up the camera to photograph him.

In 2020, Larry underwent surgery where he was expecting to have one eye removed. He was in low spirits in the days leading up to and following the surgery, and that was one of the rare times he stopped using the camera.

I remember feeling the weight of very big changes upon us.

Knowing that Larry will never be the same again coming out of that surgery, I felt compelled to pick up the camera to photograph his transformation.

In the face of impending loss, Larry had to process a lot of emotions to come to terms with what was happening. I wanted to photograph him to bear witness to his spirit.

The images you captured in Home documenting Larry’s last five months are deeply intimate and heart-wrenching. What went through your mind during the process?

As my grief deepened, my awareness of life’s transcendent beauty also heightened.

Every moment could be Larry’s last. His last time playing the piano, strumming a guitar, watching the girls play at the playground, holding them, walking, eating…

I also experienced a profound shift in what beauty is to me. As Larry approached the end of life, his body entered a process of cutting off its functions so that he stopped moving, speaking, eating and eventually, breathing.

In this stage of his life, he no longer fit neatly into the mainstream definitions of ‘beautiful’. Yet when I looked at him, prostrate and peaceful, I was overcome by beauty—a beauty I’ve never known and felt.

He was physically still with us, but it seemed to me that his consciousness had already begun shifting into a different realm where his essence resides.

Even as the light of his external life dimmed, the light of his eternal self kept glowing. I beheld this beauty. It was transcendent, and doesn’t yet have a place in our dictionaries.

Did creating this body of work shape the way you processed Larry’s passing?

Every once in a while, the girls—especially Georgia, who was 3 when her father died—will ask to look at old photos of them with their papa. It brings them joy to look at these photos and recall memories. I sometimes find myself going through these photos myself, reminiscing and grieving.

The photos are a portal to the past, a safe place for me to allow my grief to surface. A reminder of the love that was and still is present.

For your new project on grief, Still Here, you capture the process of going through a loved one’s belongings after they’ve passed. Tell us how you came up with the idea.

Naadira Aziz and I got to know each other through her cousin. Both our husbands died a month apart at the end of 2022. We hadn’t met before, but in each other, we felt seen and understood—connected by the death of our husbands, widowhood, and raising two young bereaved children.

The idea for this photo essay came about when, in March 2024—more than a year after her husband’s death—Naadira asked in a message, “Would it be OK if I asked how you went through Larry’s belongings?”

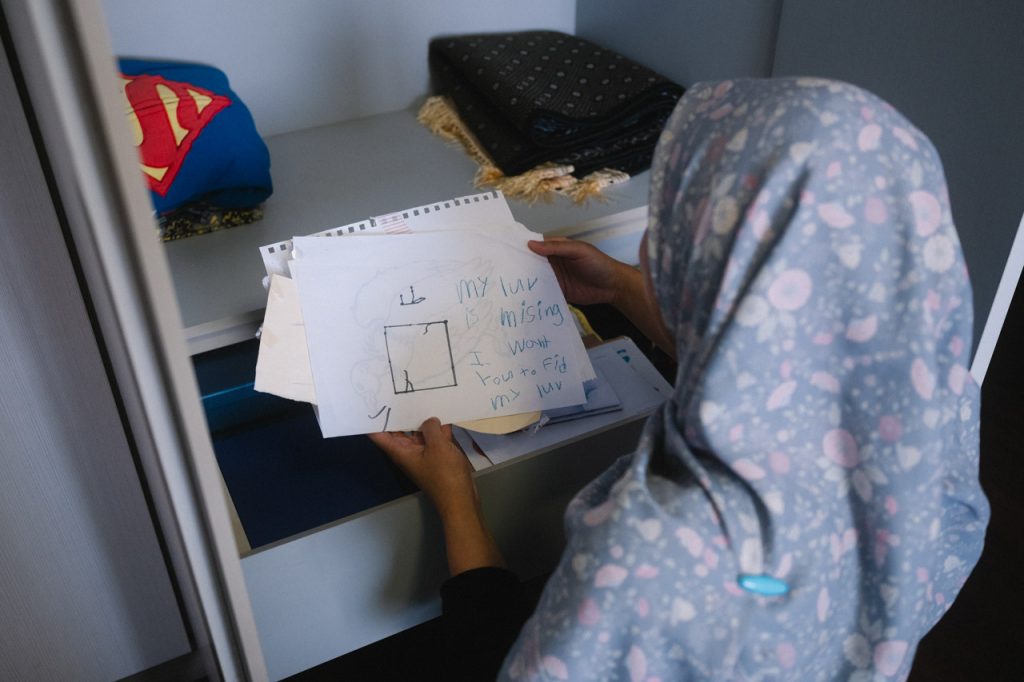

What came to be was a series of photos where I bore witness to Naadira’s grief as she went through some belongings of her husband, Hasyali, that she previously couldn’t bear to peruse. His work uniforms and certificates, his prayer mat, the clothes he wore when he died.

Some items, Naadira found, were too hard to put away in storage, so they went back into the wardrobe.

In the last image, Naadira pauses before leaving home to look at Hasyali’s backpack, which has remained hooked on the wall, unpacked since the last time he left it there. It’s a daily reminder of him—and yearning for a life that once was.

The project is layered with my own grief. It is not lost on me that these images were shot on my late husband’s camera that I brought to Naadira’s home, carried in a backpack Larry used to carry for his photo shoots.

Still Here doesn’t refer just to our loved ones’ physical belongings; it also alludes to the love and grief, as well as our children’s, that we continue to carry long after the people we love have gone.

There’s something deeply affecting about this particular photograph. Can you share what was happening in that moment?

Naadira had taken out a bag of clothes that Hasyali last wore when he was alive, and holding his Superman hoodie brought back strong memories and emotions. This is what she shared about this moment:

“I remember thinking this doesn’t smell like him anymore. It smells like mothballs. Even after massive decluttering, leaving a job, and going through therapy, I was holding on to hope that I still had one final trace of him that couldn’t be taken away. But when I smelled that jacket, it hit me that it was gone. He was truly, organically, gone. This photograph reminds me of the moment that gave me release—even if it was a painful release. In everyone else’s eyes, we looked like we were doing ok, moving on. Even I believed I had moved on. But now I know there’s no moving on in grief… You just move through it and with it. It’s like my heart expanded from the moment I truly accepted he’s truly gone. And I realised there was room for so much more.”

Naadira did not feel ready to pack away this set of clothes at the time, so they went back into her wardrobe.

Her words about this moment are poignant. Even though she did not ‘make space’ in her wardrobe, internally she had arrived at acceptance and therefore, an expansion within her.

For me, this moment is also a very real representation of grief having its own timeline. I was moved that Naadira honoured her grief and where she was at.

How do you navigate the intimacy of documenting something so deeply personal—not just for yourself, but for others too?

I tend to get into a state of flow. Most of my attention is on the people I’m photographing, the scene, and the light. In this state, the volume dial in the part of my brain that accesses my feelings and thoughts is temporarily turned down.

Occasionally, my own grief may pay unexpected visits and become louder. In these moments, I quickly notice the lump in my throat, breathe through it, and then adjust the volume again to refocus on my role as a photographer.

As a documentary photographer, I must set aside my own stories to truly see and hear the person before me. After the shoot, I return to my personal feelings and stories, allowing myself time to process them.

What does it mean to keep or to let go of something a loved one once owned?

I’m learning that every grieving person’s process is different. For some, letting go of physical possessions may be an important part of the grief process. For others, holding on to certain belongings may help them cope with their grief.

In my case, I gave some of Larry’s belongings to his friends, whom I know will continue to cherish the items. I’ve also donated some other items, but I’ve chosen to keep some things Larry once treasured—his cameras, photo books, coffee machine, acoustic guitar, select pieces of clothing and accessories…

Many of these are now being used by me and bring me joy and pleasure as they once did for him. I love being able to make new memories with what once was his.

Have these photographic projects offered you any sense of closure—or perhaps something else—in your own journey through grief?

Closure hasn’t been something I’ve sought after, perhaps because I don’t think of grief as necessarily having an endpoint.

I resonate more with the notion that we can integrate grief by both grieving fully and living fully.

Still Here has been a fulfilling and meaningful project. When I asked Naadira if I could document her process of going through Hasyali’s belongings, I didn’t begin with a clear goal.

But fate had its own way of drawing us closer. Recently, Naadira and I became certified Grief Educators, and we now hope to build something together by offering support for grieving parents and children.

Through this, we hope to foster braver, more compassionate conversations around loss, and in doing so, help nurture a deeper understanding of grief in a society that often struggles to hold space for it.

What kinds of conversations do you hope your work will open up, especially among families?

While I am coming across more content about grief on social media lately, it still isn’t something most people are comfortable seeing or talking about.

In a society that expects the bereaved to finish mourning within two to five working days, grief tends to be seen as inconvenient.

We commend people who seem to have ‘moved on’ and celebrate their ‘strength’. This paints a false picture that grief is a sign of weakness and leads to unrealistic pressure on people who are grieving.

I hope for grief to be normalised so that people of all ages have safe spaces to feel and process their grief. After all, almost every one of us will experience loss at some point in our lives.

For these reasons, I am very thankful for how willing Naadira was to be vulnerable in front of the camera.

To me, when I see her photographs, I see strength and beauty. Perhaps others will see this too.