All images courtesy of Alaric Tan and The Greenhouse unless stated otherwise.

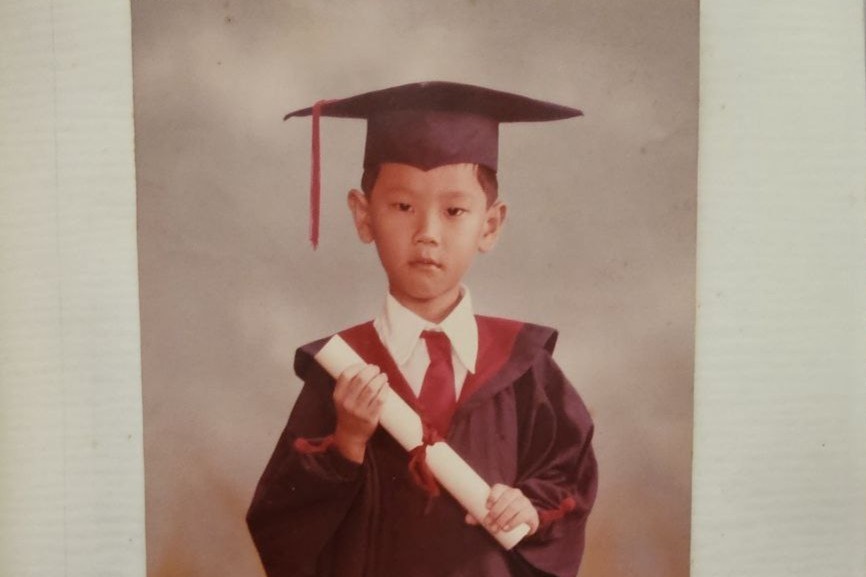

Alaric Tan has a calming aura. When you speak with the man, you can almost see his mind sprinting quietly, as if he’s weighing possibilities and choosing words with care.

Yet, beneath that calm is a past tinged with blame, rejection, and many years lost to drugs.

“I used to believe something was broken in me,” the 47-year-old says.

“But what I needed wasn’t fixing. It was safety.”

Alaric and I both attended Maris Stella, a Catholic boys’ school, so I know he’s not exaggerating when he recalls the abuse suffered by students who were different.

Seeing overweight and effeminate classmates ostracised—and sometimes even manhandled—he felt a responsibility as the head of the student council to protect them.

“I did my best to look out for everyone,” he reflects. “But when I began to feel maybe I too was different, I started feeling unsafe.”

He avoided bullies by masking his growing attraction to other boys. Yet the tension gnawed at him.

“I felt pulled in two directions: I wanted to defend the bullied, but revealing myself would make me a target.”

Self-preservation meant self-erasure. And in those hidden corners, self-loathing took root. That longing for a safe space never left him.

Years later, it became the seed of The Greenhouse—a rare sanctuary in Singapore for those weighed down by shame and silence to turn their pain into purpose.

Deep-Seeded Rejection

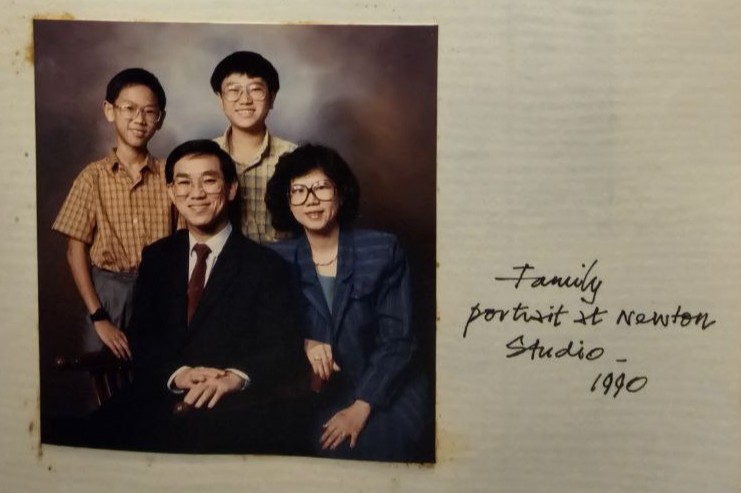

Seeking safety, he came out to his family. It was met with disappointment, anger and conversion therapy.

“A conversion therapist told me I was broken, but if I prayed hard enough, I could be made whole again.”

Alaric candidly shares that the darkest days of his childhood were marked by his parents insisting that homosexuality was his fault. The conversion therapist deepened the wound, convincing him he was broken at his core.

Alaric had to endure two cycles of the harmful practice, and it only amplified his shame. Nights stretched into dawn as he lay awake, terrified of being discovered. Eye contact made him flinch; friendships felt unsafe.

“I feared that my imperfection would taint others. Why would I inflict myself on them?”

When his parents sent him to an “ex-gay” clinical psychologist who disapproved of his “lifestyle” and prescribed antidepressants, his sense of failure and guilt deepened.

“Why is it so expensive to keep me alive?” he recalls thinking. That self-hating narrative would shadow him for years.

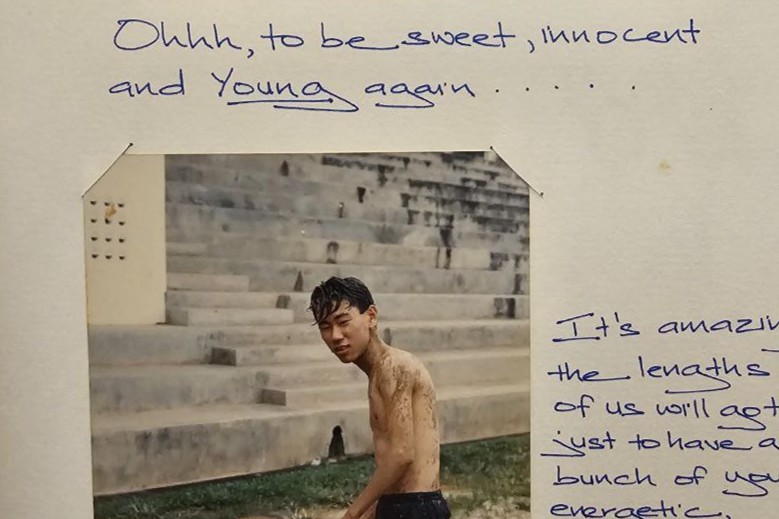

University brought both promise and danger. In college, he discovered marijuana, then ecstasy. He found his racing anxiety slowing down like a gentle hand on a spinning wheel.

“It was such a powerful sense of relief,” he divulges.

But the fleeting relief quickly turned into dependence, with weekend ecstasy binges in Bangkok giving way to frequent use of ketamine and meth.

After graduation, he landed a job in business consultancy, where he excelled professionally while concealing his use. It was when he struck out to start his own business that the pressure shifted his drug use from occasional escape to daily dependence.

It took a drug-induced car crash to jolt him into seeking help. Alaric booked a flight to The Cabin, a rehab centre in Chiang Mai. For the first time, a psychologist told him that his drug use didn’t stem from moral weakness, but from the trauma of conversion therapy.

“I flew into a rage,” Alaric recalls, his voice breaking slightly with embarrassment.

Rage not at the psychologist, but at the years stolen from him by those who insisted his suffering was his own fault.

The anger drove him even deeper into narcotics. It got to the point where he was completely unable to function without drugs.

“I needed at least 1ml of GHB (gamma hydroxybutyrate) every hour of every day just to get out of bed and complete simple tasks—this was excluding other drugs that I was using,” he reveals.

“My boyfriend of 14 years said he no longer believed that I was trying to quit, and left me.”

Whenever Alaric tried to stop, he would get anxious, depressed or even suicidal. During the stillness of those clear-headed moments, piercing childhood memories would creep in alongside feelings of being unloved and unwanted.

In 2016, fate caught up with him. When his drug dealer was unavailable, Alaric turned to his runner—unaware the man was under police surveillance.

The arrest that came after could have been just another low point, but six months in the Drug Rehabilitation Centre became a wake-up call for Alaric. Upon his release, he poured his energy into chairing support groups and starting anti-drug initiatives—a first attempt at turning pain into purpose.

But the real crossroads came a year later, in relapse. After a week-long binge of meth, GHB, and ecstasy, Alaric was gripped by an amphetamine-fuelled psychosis. Hours before he was meant to chair a support group meeting, he found himself fighting not only the drugs in his system, but also the humiliating irony of leading others while he was falling apart in front of them.

Twitching and sweating, eyes dilated, he braced himself for judgment. Instead, the members embraced him.

“The craving for drugs left the moment I felt truly seen,” Alaric says, his eyes widening at the memory of his key turning point.

“If you believe in a higher power, it felt like one had given me a choice at that moment: to continue living in pain, or to live a life of purpose.”

That moment birthed The Greenhouse.

Nurturing What Wouldn’t Survive Otherwise

After chairing countless support groups and rehab sessions, he decided it was time for a permanent home for these initiatives.

When he found a modest but conducive space in Little India where his work could take root, he sold off his car, his business, and gave up his rental apartment—raising about $100,000 to start The Greenhouse.

“First of all, the building we were in was green,” Alaric smiles.

“But over time, the name came to mean a place that nurtures things that don’t usually survive in the wild.”

The Greenhouse isn’t just a recovery centre for drug users and trauma victims. It’s a community that reminds people there’s nothing faulty with them—that true healing is not shame-based. It starts with feeling safe and understood.

Alaric relies on a trusted core team and board of directors, but The Greenhouse family also fosters a culture of honesty and vulnerability, where anyone can step in and show up for another.

This community welcomes those who face shame, fear, and discrimination. It was only natural that many from Singapore’s LGBTQ+ community, ethnic minorities and those living with HIV felt drawn to The Greenhouse. It was the only place where they didn’t feel marginalised, where they could be themselves.

Meetings such as 12-step programmes and group therapy often begin by celebrating abstinence milestones. Members check in with one another, sharing their struggles and feelings, then exchange coping strategies and ways to reframe challenges without turning to substances.

“Addiction is rarely just about drugs,” Alaric affirms. “It is often about unspoken pain, unprocessed trauma.”

At The Greenhouse, recovery isn’t a set of scheduled programmes on a page. It’s built within the consistent check-ins, the safe spaces where stories of relapse and triumph are shared, the hands that reach out to steady someone struggling, and the small victories celebrated together.

Behind every shared meal and gardening session is an evidence-based recovery model that tends to biological, psychological, social and spiritual needs.

Mohamed Imran, 48, who is the Founding Director of the Dialogue Centre, helps train The Greenhouse’s peer supporters and counsellors.

He vouches that The Greenhouse fills a critical gap at the intersection of recovery and sexual identity in Singapore.

“It offers a safe space for people who are too often overlooked to work through their struggles,” he notes.

Without that safety net, Imran has seen people spiral—into depression, fractured families, worsening mental health, and even substance abuse.

“That’s why The Greenhouse matters,” he adds. “I’ve watched their former clients grow stronger here, and some even return as peer supporters themselves.”

Here, clients learn to name both their Big T traumas—violence, abuse—and their small t traumas: the casual cruelties of rejection, ridicule, and religious guilt.

In recognising these wounds, healing becomes possible.

One young man, for instance, could not kick his drug habit despite repeated attempts, and the frustration among his support group’s members slowly became visible.

Only when he opened up about a traumatic incident—when his father once pushed him down a flight of stairs, leaving him convinced he should never have been born—did the cycle begin to break. Upon verbalising that poignant memory, his therapy began to see results.

Within 90 days of being held in safety, he stopped abusing drugs. It was one of The Greenhouse’s fastest-ever recovery cases.

Alaric’s approach to recovery support is unconventional, which can make it hard for others to grasp—and easy for them to criticise.

He has been chided for counselling drug users instead of reporting them, mocked for offering his services free of charge, and even accused by some in the LGBTQ+ community of bringing shame upon them. In a 2018 news article about The Greenhouse, one online commenter went so far as to suggest Alaric should be hanged rather than celebrated.

Such sentiments came from people who had no idea that Alaric had already cashed in his health insurance and retirement plan just to keep The Greenhouse’s lights on.

Yet the deepest cuts came not from strangers but from allies—when The Greenhouse finally secured charity status, NCSS (National Council of Social Service) membership, and IPC (Institution of a Public Character) status, long-time partners dismissed him as a sellout.

Those moments stirred insecurity, self-doubt, even impostor syndrome. But in the same way he urges clients to lean on community, Alaric draws strength from The Greenhouse’s culture of openness and vulnerability.

“I shared my thoughts and feelings at our recovery meetings, then forged on,” he recalls.

“These were painful experiences I needed to go through, so I could support our recovery ambassadors in sharing their own stories when they were ready.”

Where Good Work Thrives

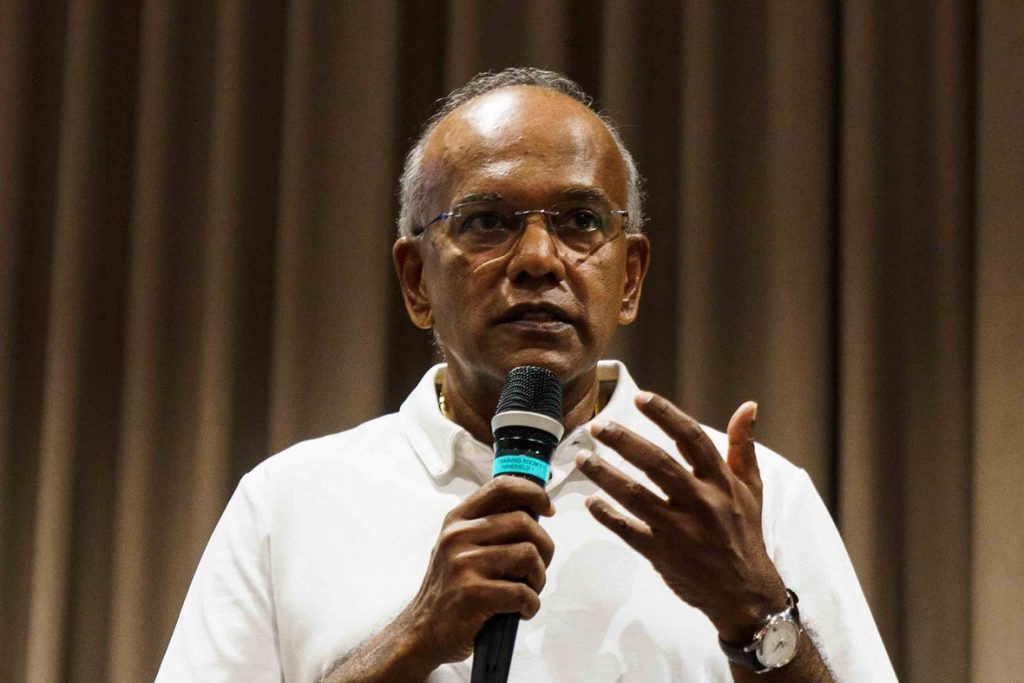

Over time, The Greenhouse has gained recognition, even ministerial support. Upon Alaric’s invitation, Coordinating Minister for National Security K. Shanmugam visited the centre in 2021 and commended the founder on his efforts. He graced The Greenhouse once again in July 2025 as the guest of honour at its Mid-Year Celebration.

“We need to reach out to every part of the community, to be inclusive, to save as many lives as possible,” said Minister Shanmugam at the event.

“A good society means helping everyone, regardless of background, achieve their full potential.”

For Alaric, these words affirmed both the work of his team and the dignity of his clients. And he’s tirelessly raising funds for new initiatives on the horizon—vegetable gardens, a soup kitchen, even an animal shelter. The Greenhouse continues to grow as a place where survivors can pay their healing forward.

“Contributing to society restores self-worth, and doing that shoulder to shoulder helps us focus on our similarities, instead of our differences,” Alaric affirms.

The Greenhouse has also profoundly impacted former clients like Nazir, 41, who learned how to cope with daily struggles and manage his emotions.

“It’s a safe place for anyone seeking help with recovery,” Nazir says. “Here, we can reintegrate into society without being judged or retraumatised by our past.”

As a gay Indian-Muslim man living with HIV, Nazir faces rejection constantly, even from his own community. But The Greenhouse has shown him the power of focusing on what he can control.

“The Greenhouse has lifted me up and taught me how to take charge of my thoughts and feelings. Because of that, I’ve started to love myself.”

Nazir’s story underscores how The Greenhouse transforms not only individual lives but the very way its clients see themselves, laying the foundation for resilience that extends far beyond the centre’s walls.

Alaric has watched this ripple effect extend to his clients’ families as well, as loved ones begin to understand trauma and learn how to support recovery.

“When someone starts to heal, the people around them begin healing too,” he reflects. “When I see mothers of our clients lead support groups, it’s a heartwarming full-circle moment.”

Towards a Gentler Society

“I like the saying, ‘Shame dies when stories are told in safe places’,” Alaric tells me triumphantly.

He believes in another saying: Nothing is wasted in God’s economy. Even his darkest chapters have been repurposed into a source of light for others. That is the quiet power of redemption—not in erasing the past, but in re-shaping it into a safe space for those who still wander in shame.

“Many of us are in pain from something, or running from something,” he says. “The only way forward is to lift one another up.”

That longing for safety—the shelter he once needed but could not find in his youth—has now borne fruit in The Greenhouse. Here, brokenness is not a verdict but the soil from which resilience grows. It’s a reminder that healing begins not with fixing what is ‘wrong’ in us, but with being held in safety until we can grow again.

“One organisation won’t change the country,” Alaric admits. “But we can be part of a larger movement towards openness, compassion, and care.”

And perhaps that is the lesson his journey leaves us with: that healing is never a solitary endeavour. It is collective—built in small, patient acts of listening, acceptance, and care. True healing doesn’t erase the scars, but teaches us how to grow around them, together.