‘After the Vote‘ is a RICE Media series where Singaporeans from all walks of life share their hopes for Singapore—the changes they envision, the values they want to uphold, and the future they want to help shape.

We take a step back to explore the bigger picture: What kind of Singapore are we building beyond this election? Through these conversations, we uncover the aspirations and concerns shaping the nation in the next five years and beyond.

The views in ‘After the Vote’ are those of the interviewees and based on their experiences; they do not reflect the publication’s stance.

All images courtesy of Lester Lim unless stated otherwise.

For most of Lester Lim’s childhood, school was a struggle. He didn’t quite know where he was headed in life—only that he wanted to pursue art.

Back then, there wasn’t much awareness of dyslexia. All the 54-year-old knew was that reading and writing felt difficult, but art? It just made sense.

For years, Lester poured himself into any kind of creative work he could find—from painting posters to commercial design work. But by his 40s, he was feeling spent.

“It paid the bills, but everything felt too clean, too calculated. I got tired of making things that looked ‘right’ but didn’t feel real,” Lester tells RICE.

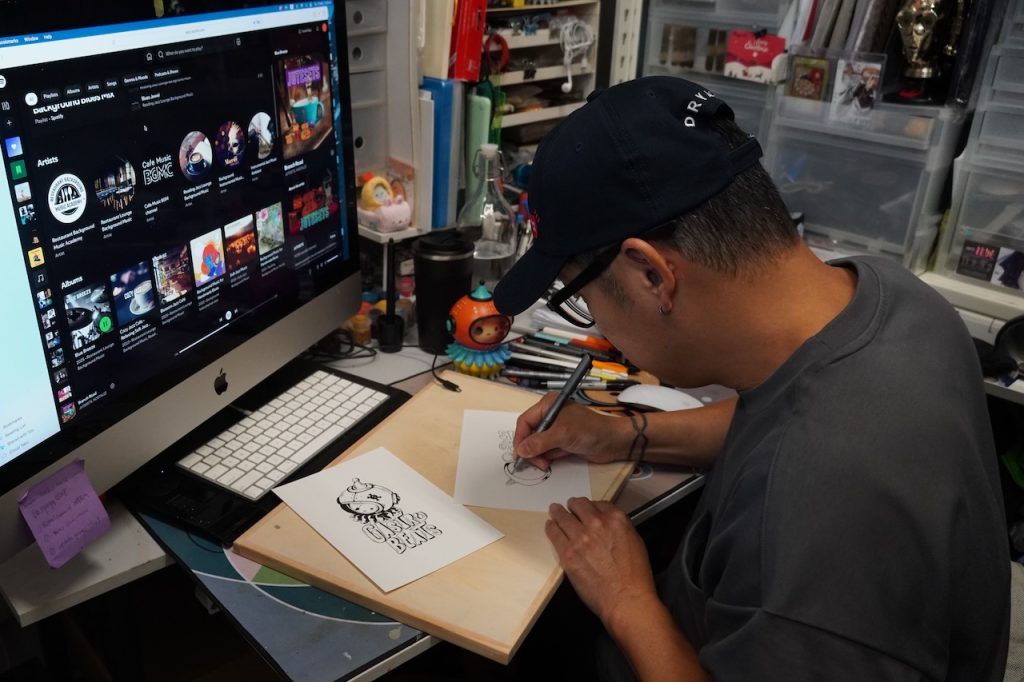

That frustration turned into experimentation. Around 2018, Lester began designing for himself again—strange, playful characters that helped him process feelings he couldn’t quite name. One of those sketches became Jelilo, a jellyfish-like figure wearing a space explorer’s helmet.

“Toy-making gave me a way to tell stories in a form that felt tangible, emotional, and accessible. The designer toy world, especially, offered space to be weird, vulnerable, and real—and that’s exactly what I needed,” says Lester, who now creates toys under his brand, gagatree.

Jelilo was an ode to his daughter’s experience of being bullied for having dyslexia, and his own realisation that he had been living with it, undiagnosed, his whole life. The toy wasn’t created for commercial success.

But when Lester finally put it up for pre-order in 2020, it sold out in three days. Since then, the quirky, wide-eyed figure has garnered fans worldwide, proving to him that art, creativity and design are valid ways to tell personal stories.

RICE is taking a longer-term view towards the Singapore we’re collectively building. And Lester has plenty to say about building a Singapore where artists can thrive and where every child has the space to be creative.

What is one change you hope to see in Singapore by 2030 that would make life meaningfully better for people like you?

I hope to see more creative freedom and public support for artistic experimentation, especially from younger, lesser-known artists. Singapore’s creative scene has incredible potential, but we often have to shape-shift to fit commercial or traditional expectations.

I didn’t pursue a formal education in art, so stepping into visual art and toy design felt like walking into uncharted territory. When I first started experimenting with creating characters like Jelilo, I wasn’t sure how it would be received. It wasn’t “cute” in the usual way, and it didn’t follow what was trending. But Jelilo was honest, and it came from personal experiences with bullying and the need to channel something raw into something hopeful.

In Singapore, there’s often this pressure to create things that are commercially safe or easily digestible. I’ve had moments where I was told to tone things down, make them more palatable. But I realised the more I embraced what felt unfamiliar, even uncomfortable at times, the more people connected with the work on a deeper level.

The journey to finding my footing was about letting go of the need to conform. I had to give myself permission to play, to be weird, and to be vulnerable. And it’s why I hope we can build a culture that gives young creators that same freedom—to try, to stumble, and to be unapologetically original.

A society that embraces play, weirdness, and vulnerability in the arts would be a game-changer. Not just for artists, but for how we collectively express who we are.

What’s a challenge Singapore must overcome in the next six years to stay a place where people want to live and thrive?

We need to break out of the fear of failure. Everything here is so tightly optimised—from education to city planning—that risk-taking feels unsafe.

I’ve seen that fear-of-failure mindset in the creative industry here. There’s this unspoken rule that your work needs to look ‘polished’ or commercially viable before it’s even shared.

I see many artists playing it safe by sticking to what’s trendy or commercially proven just to survive. There’s a real pressure here to make things look polished and market-ready from the start, which makes it hard to take risks or develop a unique voice.

At the same time, I’ve seen some creatives head overseas because they feel there’s more freedom and appreciation for experimentation elsewhere. It’s not that the talent isn’t here—we have so much of it! But without support systems that allow for failure and growth, we risk losing our most original voices to other cities that provide them room to breathe.

Growing up, I felt that pressure too. Like many Singaporeans, I was raised in a system where mistakes felt costly. You don’t try unless you’re sure you’ll succeed. That mindset really stuck with me for a long time.

What helped me break out of it was honestly… getting tired of playing it safe. I started to realise that some of the most meaningful creative breakthroughs came from accidents, from uncomfortable emotions, from letting go of control. Jelilo, for example, came from a deeply personal place. It wasn’t calculated, and that’s why it resonated.

The conviction came when I saw how people responded to the honesty and imperfection in the work. That gave me the courage to keep experimenting, even if it meant not everyone would ‘get it’. I think we need to normalise that by getting people to try weird things without always demanding a perfect outcome.

The future won’t be built by people who always play it safe. Whether it’s in tech, art, or social change, we need to create room for trial, error, and reinvention.

If you could introduce a new national priority for Singapore, what would it be, and why?

I’d prioritise the mental, emotional, and creative well-being of our people.

Productivity is great, but what’s the point if we’re burnt out and disconnected from ourselves? Art, humour, and imagination aren’t luxuries; they are survival tools. They help us process who we are and where we’re going.

Art has always helped me process what I couldn’t put into words. It also gave others something to relate to. People have told me the character made them feel less alone, and that’s when I realised: creativity isn’t just expression, it’s connection.

For many artists I know, creating art is a way to cope with pressure and navigate their identity. That’s why I believe mental and emotional well-being should be a national priority. Supported not just by policies, but by giving people space to create, feel, and be human.

What small shift—policy or mindset—could make a big difference in the daily lives of your community?

Stop seeing art as a ‘nice-to-have’. Creativity shouldn’t just be a decoration slapped onto an HDB wall. It should be part of everyday life—how we learn, how we build communities, and how we care for one another.

It’s a big part of why I went into toy-making. Toys are emotional objects. They spark imagination, nostalgia, and joy. They’re accessible art, especially for people who might not engage with galleries or traditional forms. With Jelilo, I wanted to create something that could live in people’s everyday spaces and still carry meaning.

I’ve always been inspired by artists who blur the lines between play and message, artists such as KAWS or Takashi Murakami. Their work isn’t confined to white walls; it lives in public, in culture, in conversation.

That kind of impact demonstrates how creativity can shape our perception of the world and one another. If you take KAWS’ work for example—the most popular of which are the Companions—it embodies the feelings of vulnerability and loneliness. The human condition.

We need more of that in Singapore: creative work that’s part of daily life, not just a backdrop to it.

The more we value creative thinking, the more resilient and inspired we’ll be as a society.

Singapore moves fast. What’s one thing we need to slow down for?

We need to slow down to ask better questions. Not just “What works?” or “What’s efficient?”

Questions such as “Will this sell?” or “Is this practical?” are so common here, but they shut down imagination before it even begins. They’re focused on outcomes, not meaning. When we only ask what’s efficient, we miss out on what’s emotional, what’s human.

For me, better questions start with curiosity, not certainty.

I ask things like, “Why does this make me feel something?” or “What if we tried something that doesn’t make sense yet?” These kinds of questions open up space for play, vulnerability, and discovery. They may not lead to immediate answers, but they lead to more honest ones. And I think that’s what we need more of.

It is with this very notion and philosophy that my wife and I started gagatree. We wanted to pursue conversations and expressions via our art and toys. Times are changing. Consumption patterns are changing, and information overload is real. There are conversations happening on every platform but sometimes we need to take a step back and see if the conversation actually means something to us.

I think we often fall into transactional mindsets, especially in a fast-paced environment like Singapore. We’re taught to optimise everything, even our relationships.

When we stop asking, “What can I get?” and start asking, “Who is this person?” we create space for real, lasting connection. That’s where meaningful work and relationships begin.

What’s one thing about Singapore you’d want to protect for the future?

Our children. They deserve more than just a safe environment. They deserve one that actively stands against bullying. Jelilo was born out of that hope: to speak up for the quiet ones, the misfits, the kids who get picked on for being different.

Jelilo was born from my own third-hand experience with bullying. I wanted to create a character that embodies softness, resilience, and being unapologetically yourself.

The jellyfish felt right: quiet, gentle, but strong in its own way and when they band together. The light from the jellyfish emits a sense of hope. Jelilo became a symbol for the misfits, the sensitive ones who deserve space and protection. It’s not just a toy, it’s a reminder that it’s okay to be different.

Bullying still happens in schools and on social and digital platforms, and too often it’s brushed off as “kids being kids”. That mindset has to change. Protecting our children means building a culture of empathy, not silence. That’s the Singapore I want to help shape.

Besides building a culture of empathy, I want to keep Singapore’s diversity, or more generally, the mix of cultures and traditions that make us unique. I also want to protect our spirit of resilience and innovation.

It’s these strengths that make Singapore a caring, inclusive, and forward-looking home.

In 2030, what kind of Singapore would you be proud to call home?

A Singapore that doesn’t just celebrate success but also honours expression.

Right now, success in Singapore often feels tied to achievements such as grades, high-paying jobs, and titles. But from my experience, that can leave little room for creativity or expressing who you really are. I’ve seen people hold back their true selves to meet expectations, especially in more traditional settings.

The Singapore I imagine in 2030 values success differently—not just by results, but by the courage to express, experiment, and connect. It’s about making space for all kinds of talents and voices, where people don’t feel like outliers, but part of a bigger, thriving, creative ecosystem. One where people feel brave enough to be strange, to be soft, to be loud, and to be real.

One of gagatree’s mantras is “Don’t Forget To Play.” Singaporeans are too serious sometimes. There needs to be balance.