Photography by Thaddeus Loh / RICE Media.

“Wow.” My jaw dropped open as I let my inquisitive eyes wander around … As I moved slowly through the space, I could not help but let my fingers touch the furniture as a sense of warmth swept through my body …

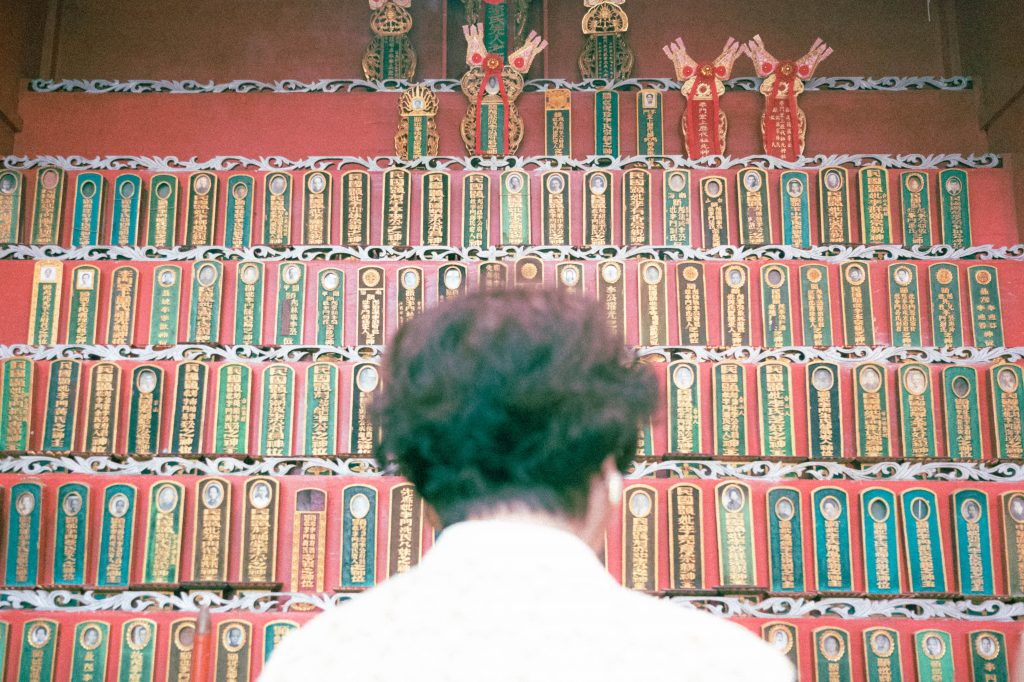

I caught sight of my own reflection in the mirror. The opposite facing mirrors formed an infinitely smaller me in every reflection, as if revealing how minute one is in the universe. The black-and-white portraits hung on the walls smiled upon me, as if reassuring that no matter how small or misunderstood one was, one has a role to play and contribute.”

Everyone has a defining moment in their life and, for heritage researcher Lynn Wong, this was one of those. Her short story—aptly entitled My Second Home—recounts the first time she visited a clan association at the age of 15.

“I was there to learn kung fu and lion dance,” says Lynn, a fan of Wong Fei-hung and traditional martial arts since young. “But it opened my eyes to a whole new world.”

The trip, you see, had been nothing short of an epiphany: “Before that, I was only able to learn about history through social studies and TV shows. Entering the clan however felt like entering a time capsule undisturbed by the hustle and bustle of modern Singapore.”

The thunderstruck teenager began spending more and more time at the clan. In her story, she recalls a strained late-night encounter with her mother after one such incident:

““一个女生为什么要练到这么晚才回家?” (“Why does a girl have to train till so late?”)

“I heard my mum’s disapproving voice as I unlocked the house door. I looked up at the wall clock while avoiding my mum’s intense gaze. It was already past midnight.

“Because I’m not Cinderella,” I joked in an attempt to ease the tension.

She was certainly not pleased with my reply … Growing up in a traditional Chinese family, coming home late was considered unacceptable for a girl, especially when the reason was training in martial arts late into the night at a clan association—a place stereotypically male-dominated and some say associated with secret societies.”

Lynn had fallen in love without realising it. But unlike other childhood infatuations that are fickle and fleeting, this one would lead her to exciting new discoveries.

Fast forward 17 years later to a typical weekday morning at the Kwong Wai Siew Lee Clan Association. All was quiet, except for the clicking of a camera shutter. Now 32-years-old, Lynn—who’s lost none of her youthful chutzpah—is busy capturing the clan’s sombre exterior with her camera. It is one of the handful of clans in the vibrant enclave of Ann Siang Road that have survived the onslaught of time.

Clad in a cheongsam, Lynn is modern-day heroine, armed with more than just a clunky DSLR. She also possesses a psychology and business degree from NUS, several trophies in traditional Chinese martial arts, and a life mission.

Only five years ago and with her parent’s full support, Lynn gave up her PhD at INSEAD to be a full-time champion of Chinese culture and heritage. She now holds a leadership position in five clan associations—including Kong Chow Wui Koon—and is in a race against time to document Singapore’s remaining clans before they disappear forever.

For the uninitiated, clans once served as “embassies” for newly arrived immigrants from China, offering networking and commercial opportunities as well as lifelong friendships to those who have travelled far from home. Now stripped off of their original purpose, many clans are struggling to remain relevant.

Lynn, however, believes they are more important than ever.

“These clans existed to serve our forefathers,” she said. “They’ve touched lives and they’ve helped in nation building. I believe it’s our responsibility to preserve them, because they remind us of the struggle it took to get to where we are today.”

Not many Singaporeans share her sentimentality. Of the 500 or more clans that were established in the country, only about 200 have remained, according to Lynn.

“People often ask why is there a need to preserve so many clans. Why can’t there be an umbrella clan instead?” she says. “That’s because we’ll be losing a lot of diversity … China is so big, and each of these places have their own produce, festivals and language. Canton alone has at least 16 distinct districts.”

These days, Lynn is all about damage control (“I thought I could revive some of these clans but I now realise how naive I was.”). She goes traipsing around the city salvaging mementos—badges, old photographs, even ancestral veneration scriptures—of soon-to-be shuttered clans.

Recalling these incidents makes her grimace: “When I was at one of the clans, I spotted some old manuscripts in a trash bag. It turns out they were account ledgers from the Qing Dynasty! But the worst part was that the people who threw them away had no idea how precious they were.”

“This is just the tip of the iceberg. So much is being lost every day,” she says, sighing.

Of course, there are also intangible items like clan recipes and festivals that need to be recorded. Lynn whips out a photo album filled with fast-disappearing specialties like the Guo Zeng Zong, a type of pillow-shaped glutinous rice dumpling from the Song Dynasty, and the Mandarin Peel Duck, a duck-based dish featuring a golden broth, made from boiling the peel of mandarin oranges aged for 30 years.

“It’s from Xinhui and was a tribute item for the empress dowager,” she says, referring to the latter. “The mandarin peel from there can be as valuable as gold depending on how many years it is aged. Unfortunately, the man who has helped me recreate the dish has passed away.”

Lynn has compiled these recipes for Ho Yeah!, a Cantonese and Hakka food and culture festival she organised back in 2018. One of her biggest endeavours yet, it’s a subtle and clever approach to attracting the public’s attention, since food is a common denominator for Singaporeans.

The next Ho Yeah! Festival—along with other heritage-related events and exhibitions she organized—was supposed to happen last year, but that was before a virus tore through the earth, leaving a trail of wrecked plans in its wake.

It is now mid-afternoon but the Lee clan has received few visitors apart from the steady trickle of customers visiting the TCM clinic that’s discreetly set up in the back of the building. Many clans now survive by renting out available space, and this 147-year-old association is no different—apart from the TCM clinic, it also collects rental fees from an interior design firm occupying its upper floors.

The clan’s main hallway—which is redolent of 1960s Singapore, with its mosaic floor, antique furnishings and Chinese lanterns—now doubles up as a waiting area for the clinic’s patients. Its walls are mostly adorned with framed monochrome portraits of men and women—portraits that Lynn helped to painstakingly restore—and the occasional Chinese poetry scroll. Among these, a photo of the late Lee Dai Soh hangs, his bespectacled face looking placidly upon those who may or may not recognise him as the legendary Cantonese storyteller at Rediffusion.

Lynn is the only source of energy in this place—she’s now speaking with gusto whilst fiddling with her camera, oblivious to the inquisitive stares of the elderly patients.

“Even though things have been done a certain way for so long, I think many clans now realise they need to change with the times in order to stay afloat,” she says.

Sitting across from Lynn is one by-product of these changes. Madam Lee Swee Har, however, seems to be unruffled by the fact that she’s made clan history by becoming the association’s first chairperson three years ago. Things were very different when the 79-year-old was first introduced to the clan by her father at the age of 14.

“The clan leaders were always male before this, but it wasn’t something I ever pondered over,” says the highly accomplished singer and chef in her native Cantonese. “There were more than a thousand of us, and we were all like brothers and sisters. We usually played music and sang when we got together, and also occasionally performed for the radio.”

Lynn, on the other hand, isn’t impervious to this breakthrough: “Clans were once patriarchal, but I think there’s a trend towards equality. When I first joined the lion dance troupe in a clan, there was only one other female. It was even taboo for females to touch a lion’s head if it was new.”

Today, membership numbers at the Lee Clan have plummeted to just above a hundred—its one and only youth member is in his 40s. It used to be that one needed to have the surname Lee and hail from one of three districts in China (Guangzhou, Huizhou or Zhaoqing) to be able to register, but since the clan’s very survival hinges on fresh blood, regulations have relaxed over the years.

While Lynn herself isn’t a member, she is helping Madam Lee with a few events in conjunction with the Singapore Heritage Festival (most of these events are now cancelled due to the heightened COVID-19 restrictions). The pair first met back in 2017 while Madam Lee was giving a talk at the clan.

“Lynn has done a lot for us,” says Madam Lee. “I think it’s really admirable to be doing what she’s doing in a capitalistic world. She’s not motivated by money. We need more people like her.”

Beaming at the compliments, Lynn remarks: “It’s not that younger Singaporeans don’t care, it’s because they aren’t aware of all the things they could lose once these places are gone. I think we can all start by asking our family and relatives questions about our own ancestors – their name and where they come from before settling in Singapore. That way, it’s easier to find the clan you belong to.

Lynn’s own story has come full circle recently, after she discovered the identity of her own great-grandfather in a clan register.

“I never knew what he looked like until the day I saw his picture. I always thought I was a third generation Singaporean Chinese, but it turns out we’ve been here for longer.”

Join Lynn Wong in a virtual talk entitled ‘My Journey as a Millennial Growing Up in Clan Associations’ on May 29, 10am.

Are there any lesser known cultural traditions we should writing about? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.