In the coastal waters of Singapore, life finds a way.

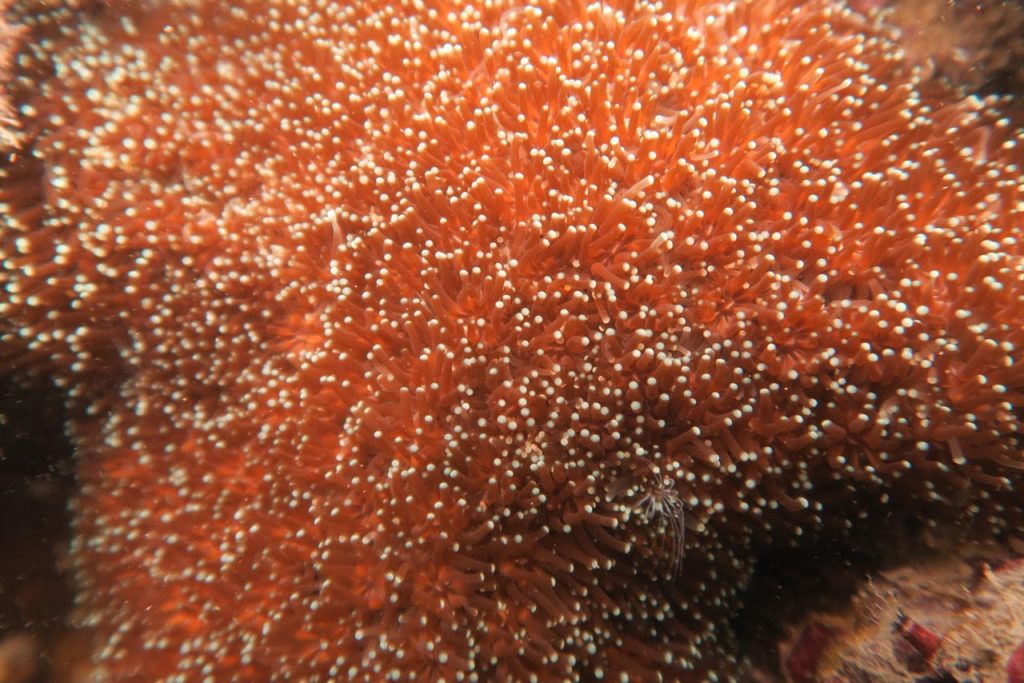

Upon the seawalls of Sisters’ Island Marine Park, for example, thousands of coral colonies in different colours and shapes manage to thrive under increasingly difficult conditions.

And their continued survival is something that all Singaporeans should care about.

Singapore’s Coral Reefs and Why Their Survival Matters

Singapore is home to 250 historically recorded coral species, or one third of the total number of coral species in the world. For such a small island, that’s an impressive statistic. Yet most Singaporeans have probably never heard of the treasures that exist off their own coastal waters.

Despite what people think, corals aren’t colourful plants, but living animals, each made up of thousands of tinier animals called polyps. These coral reefs, despite covering less than 1% of the planet’s ocean floor, houses 25% of all marine creatures in the world.

Coral reefs face many threats, the most alarming of which are the effects of climate change like rising sea levels and temperatures, ocean acidification and extreme weather events. In the commercial waters of Singapore, the risks to marine life are magnified by coastal development and well-trafficked shipping routes.

But as the MPA-planned construction of the Tuas Port demonstrates: economic development doesn’t have to come at the cost of the environment. For example, the Maritime Singapore Green Initiative consists of four programmes that seek to reduce the environmental impact of shipping and related activities, and to promote clean and green shipping in Singapore.

In 2013, together with a consortium of marine experts, environmentalists and NGOs, the MPA commissioned an ambitious coral relocation project to minimise the disturbance of the Sultan Shoal coral habitats from the nearby dredging work of the Tuas Port development.

Cheong Yiting was the MPA Project Manager in charge of coordinating the efforts.

“This coral relocation project was my first exposure to marine biodiversity and conservation,” said Yiting, who is a civil engineer by training. “But it is important to ensure that our development works are carried out in a sustainable manner, so that future generations will be able to enjoy the biodiversity we have today.”

Under MPA’s guidance, two teams of marine experts set out on separate missions to save Singapore’s coral reefs.

DHI Water & Environment Singapore: Brian Cabrera and the Coral Relocation Team

It’s said that humanity has clearer images of the surface of Mars than we do of our own ocean floors.

It’s no wonder then, that when I asked Brian Talde Cabrera about the appeal of diving, he described it as ‘entering a different world’. A world filled with amazing organisms and landscapes. Brian’s favourite dives are at night, in the watery darkness of the Philippine coast, the place where he grew up, and where, with his father’s encouragement, he first nurtured his passion for marine biodiversity and conservation.

After receiving his diving certification in 2001, Brian would spend many nights searching and studying nocturnal seahorses camouflaged on coral branches. He would also be actively involved in establishing and monitoring the effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas.

Since then, he’s logged 2,500 dives working with DHI, a research-based environmental consultancy with a mission to solve the world’s toughest challenges in water environments. His career at DHI has taken him to the waters of Indonesia, Brunei, the Maldives, and finally to Singapore.

Following a competitive tendering process, DHI was commissioned by MPA to spearhead the coral relocation efforts. Brian was responsible for planning and leading the actual coral relocation operations from harvesting and transporting 2,300 coral colonies from Sultan Shoal to their new homes at Sisters’ Islands and St. John’s Island.

To kick off the project, Brian and his team first surveyed the coral reefs at Sultan Shoal, located a few kilometers south of Jurong Island, where coral habitats remain resilient despite well-trafficked waters.

“There are certainly places in the world with clearer waters and more picturesque seascapes,” said Brian. “But Singapore’s marine habitat is unique in that there’s such rich biodiversity in such close proximity to development.”

As a patch reef prior to its reclamation in the 1970s, Sultan Shoal reached its current size through a highly modified shoreline made up of artificial seawalls. These seawalls offered the ideal conditions for Brian’s relocation team. That’s because the granite surface the coral sits on is relatively flat, making it easier to dislodge and harvest the coral colonies.

Over the course of a year, Brian and the DHI team dived up to four days a week, for several hours on end, engaged in the backbreaking work of harvesting 2,300 corals from Sultan Shoal.

Transportation was then carried out by sea.

The corals were removed from the water in small baskets and placed onto the deck of a support vessel. Each basket was covered with wet towels and doused with seawater every 10-15 minutes to prevent desiccation. They were then transferred to three recipient sites at Sisters’ Islands and St. John’s Island within Sisters’ Islands Marine Park.

After relocation, the status of the relocated corals and the overall coral and reef fish communities at the recipient sites, was monitored over the next five years. DHI also drew on their expertise in monitoring water quality conditions, by assessing any changes in parameters such as turbidity, temperature, and sedimentation.

In August 2019, Brian’s team completed the most recent survey, and reported that the coral are thriving in their new homes, with a survival rate of 82%.

Tropical Marine Science Institute (TMSI): Sam Shu Qin and the Coral Research Team

Ten years ago, while I lay in bed reading Jules Vernes’ 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Sam Shu Qin stood on a boat off the coast of South Africa, chasing Great White Sharks as part of a research study on their hunting patterns.

Inexplicably, this was the experience that inspired Sam to get her diving license upon her return to Singapore.

Marine biology was still a relatively obscure field in Singapore at the time, with few available courses of study. So Sam’s mother, having given up on pushing her daughter towards a stable career in business, allowed her to study Biological Sciences at NTU, the next closest thing.

But lab work bored Sam. What she really wanted was to be in the water studying marine animals. Again, she found the next closest thing: interning at Underwater World on Sentosa (this was before the SEA Aquarium). On weekends, she logged dives around Singapore’s waters, exploring its underwater treasures.

One day, she chanced upon a posting for a Research Assistant position at the Tropical Marine Science Institute (TMSI), as part of the National University of Singapore (NUS). This turned out to be the research arm of the MPA-led coral relocation project.

Their mission? To develop strategies to mitigate potential losses in coral reef biodiversity from coastal development, as well as to devise methods for restoring degraded coral reefs.

Sam and the TMSI team also conducted experiments to figure out the best design for building coral nurseries, as well as best practices for coral transplantation and monitoring.

When Sam first told me about coral nurseries, I’d pictured an NUS laboratory where scientists in white lab coats studied coral in vats and test tubes.

In reality, the TMSI coral nurseries at Kusu Island and Lazarus Island were built and anchored right into the ocean floor. The nurseries consisted of raised tables with mesh-nets, and the structures were weighed down by heavy iron pegs to protect them from the waves so that they don’t topple over.

Sam and the team’s work consisted of diving in and around Sultan Shoal, chipping off coral fragments and transporting them to these coral nurseries. Throughout the project, the team would monitor the growth rates and health of different species, and see how they respond to different stressors like rising ocean temperatures, high sedimentation and turbidity.

They also studied the impact of these stressors on Singapore’s reef ecosystem, conducting experiments to find out how to best manage coral predators, algal competition and coral bleaching.

Coral bleaching is a process where coral expel their colourful algae and leave their white calcium carbonate skeletons behind. This process is happening globally, most notably in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Singapore’s coral population is also being affected.

“Despite the negative headlines, there’s actually some optimism among scientists when it comes to the survival of some coral species,” said Sam. “Part of our research is about identifying and selecting those species that will have the best chance.”

For the TMSI team, identifying the most resilient species to the numerous effects of climate change and coastal development play an important role in coral restoration efforts.

To be clear: this isn’t simply a fight to save marine life. We are also saving ourselves. Coral ecosystems provide us with a vital source of seafood and are important to the livelihood of many coastal communities in the region.

“In the future, we need to come up with strategies to mitigate further coral loss due to climate change and development,” said Sam. “Even if you can induce mass spawning events, you need to ensure their survival against all sorts of natural and human threats.”

Threats to Coral Reefs Are A Threat to Singapore’s National Heritage

It’s been seven years since the MPA-led project started, and transplanted coral colonies are thriving. A testament to the vitality of Singapore’s coral species.

As for takeaways from their experience, both Brian and Sam agree: they want to see more projects like this in the future, ones that combine the focused energies and resources of the government, marine experts, and NGOs to save a precious part of Singapore’s marine biodiversity.

But money can only go so far. Each year, tons of rubbish makes its way into our local waters to snuff out coral life. Precious natural habitats like coral reefs are being destroyed by temporary moments of indifference or carelessness.

“It’s frustrating to see all your hard work being undone by a small plastic bag,” said Sam.

That’s the reason Sam co-founded Our Singapore Reefs (OSR), an organisation that brings together a group of volunteers to clean up Singapore’s ocean floors. MPA also works with OSR for public outreach events like World Oceans Day.

Perhaps the best way to raise awareness of Singapore’s coral reefs is to bring the science closer to people. Singaporeans need to understand that what we’re protecting here isn’t some distant glacier or melting Arctic ice sheet, but actual Singapore treasure.

If it gets destroyed, a vital part of our history and culture will disappear with it. So in celebration of World Oceans Day on 8 June 2020, let’s recast the narrative of Singapore’s coral reefs as a fight to protect our national heritage. Singapore can also be an example for other nations, proving that economic development doesn’t have to come at a cost to future generations.

To quote Jeff Goldblum from Jurassic Park: ‘Life, uh, finds a way.’

Sometimes it just needs a little push.

On World Oceans Day, we can all learn a little about protecting our shores, corals and life under the sea from marine pollution. Click here for a family-friendly way to learn more about the impact of marine debris on our environment.

Let’s all do our part to protect our blue planet and keep it clean and healthy.

This piece is sponsored by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA).