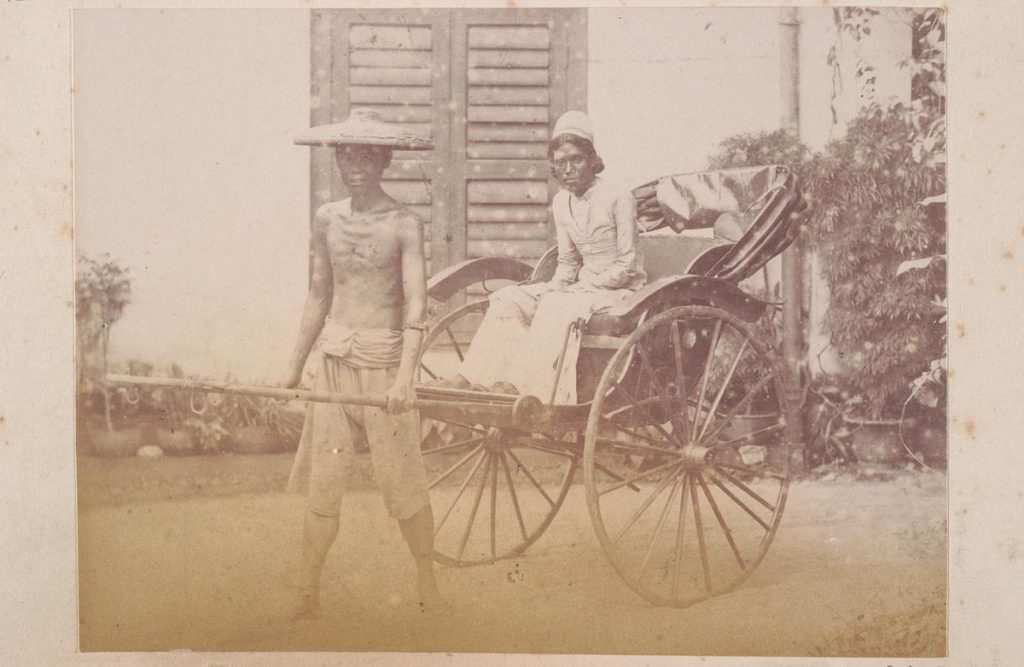

At that time, there were no laws governing workplace health and safety. Labourers and coolies—many of them immigrants seeking a better life in Singapore—would thus work as hard and as long as possible in harsh environments. Sometimes, they worked harder and longer than they could. With no one preventing them from doing so, working to death was a frequent, and expected, end.

The historian James Francis Warren describes one—out of many others—such episode:

Kwan Moh Kia, a seemingly strong, well-fed Hockchia, had passed by a Tamil house on Bukit Timah Road going towards Kranji pulling two Macao women as fares. When he was just beyond the house, Kwan Moh Kia dropped down between the shafts, on that March afternoon in 1906, when his aorta exploded like a roadworn tyre. Taju, a Tamil woman, said he never rose up again.

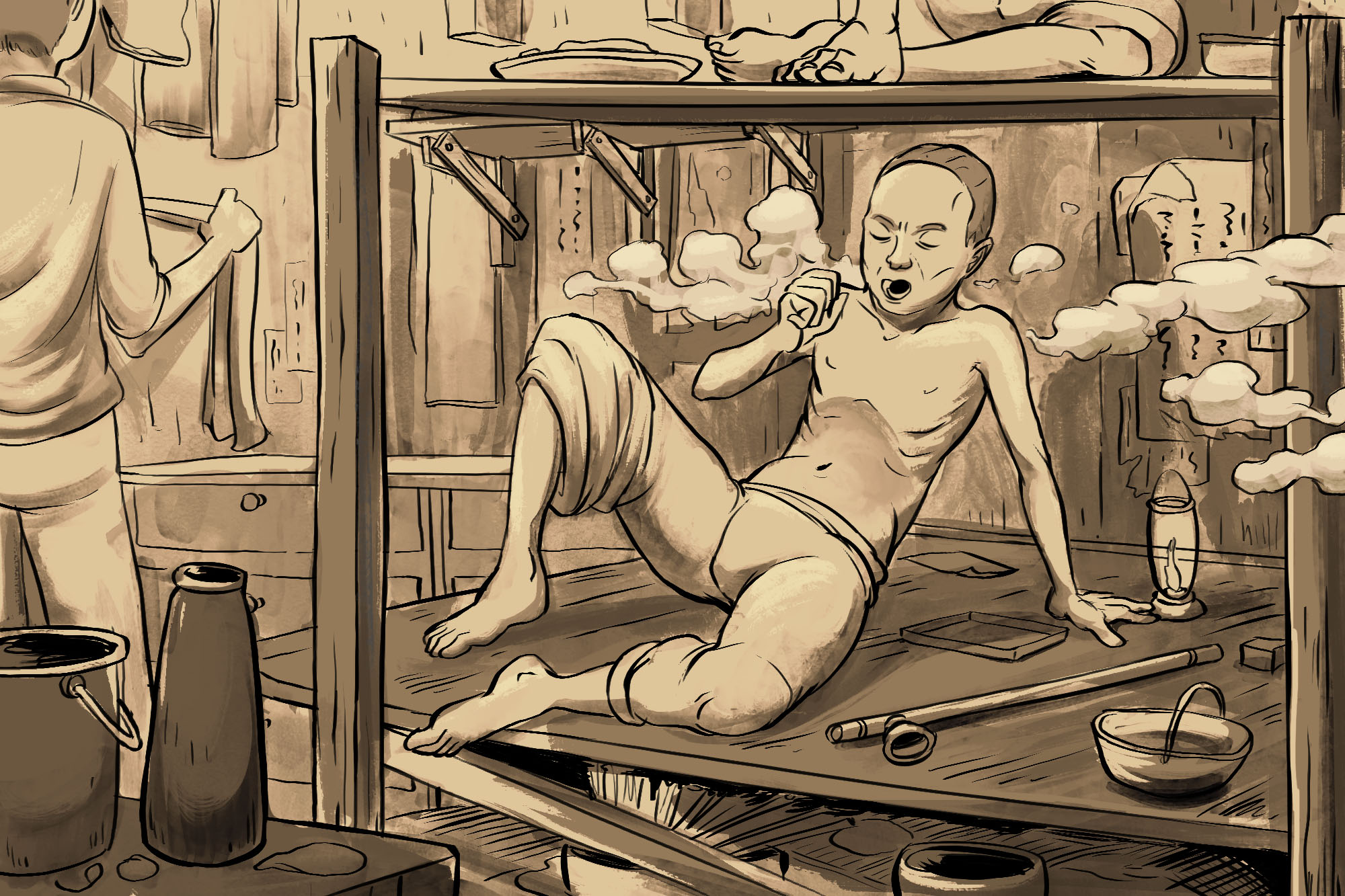

The bomb shelters in today’s BTOs would seem cavernous to these residents.

Thus, even if they were lucky enough to survive their workday, Singapore’s early immigrants still had to return to an overcrowded home that lacked ventilation and a plumbing system, factors which encouraged the spread of diseases like cholera, malaria, and tuberculosis.

Under such conditions, anyone who celebrated their 60th birthday was considered long-lived.

Without skills or education, these coolies and labourers could not find a job more conducive to staying alive. Nor could they, on their meagre pay, move to any accommodations that did not want to murder them.

Worst of all, they could not seek medical help from hospitals. Money was an obstacle, of course, but the main reason is that medical care in 1800s Singapore was highly segregated. According to the book Caring For Our People: 50 Years of Healthcare in Singapore, the General Hospital was “the preserve of European soldiers, sepoys (Indian soldiers) and the colonial government”, while government officials and Europeans had the privilege of private house visits from hospital surgeons.

Local inhabitants and natives who have taken ill? Please writhe quietly on a street corner so you don’t disturb the peace.

For these early immigrants, opium was not only a recreational drug but also an important medication. Because of its powerful pain-killing effects, opium was the drug of choice for coolies who regularly injured themselves while working and had to live with chronic pain.

In fact, opium was held in such high esteem by the 19th-century medical establishment that doctors worldwide prescribed it for conditions from cholera to bronchitis. Following their lead, Chinese sinsehs in the early 1900s would recommend opium as a treatment for illnesses that ravaged the immigrant communities in Singapore: tuberculosis, malaria, and venereal disease.

As a result, opium consumption in Singapore became widespread. The 1908 Opium Commission stated that 40% of coal coolies and rickshaw pullers smoked opium. But the Commission only surveyed people who “were visibly affected by the ‘disease’”, that is, opium smokers who were addicted to the drug as a form of recreation.

If we take into account non-addicts and patients who used opium as medication, Warren estimates that the proportion of opium users among rickshaw pullers, for instance, could reach up to 80%.

All this was observed by Eu Kong, who, in 1878, worked in a grocery store in Singapore. Trusted by his employer, he was tasked to travel between Penang and Singapore for business.

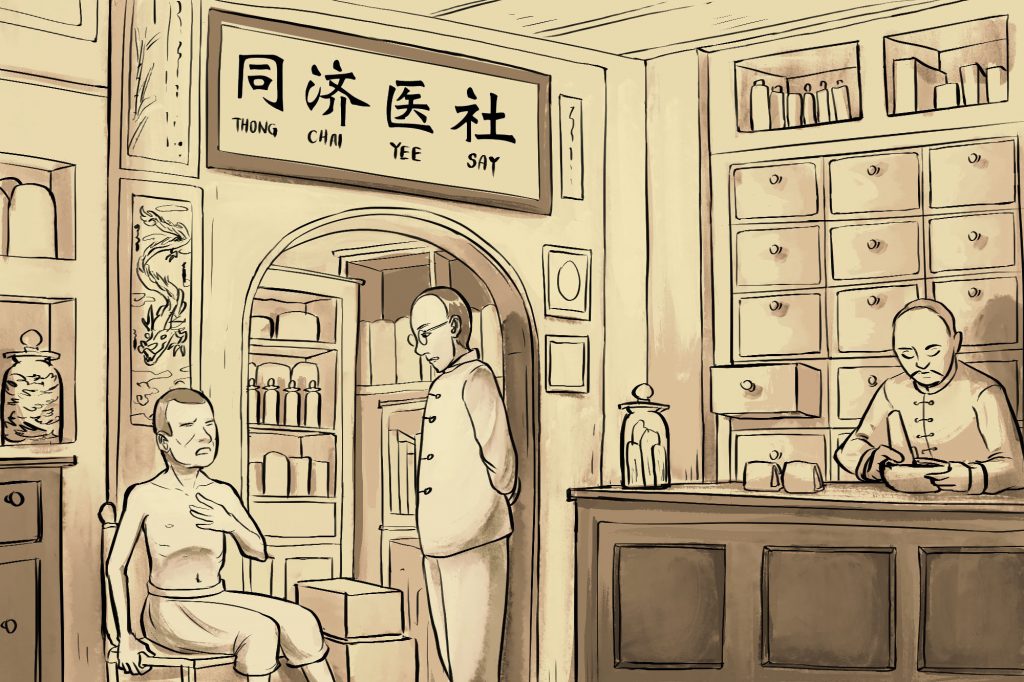

Eu Kong hoped that the shop would encourage labourers to use traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) instead of opium to treat their ailments; the shop was named “Yan Sang”, and was the precursor of today’s Eu Yan Sang.

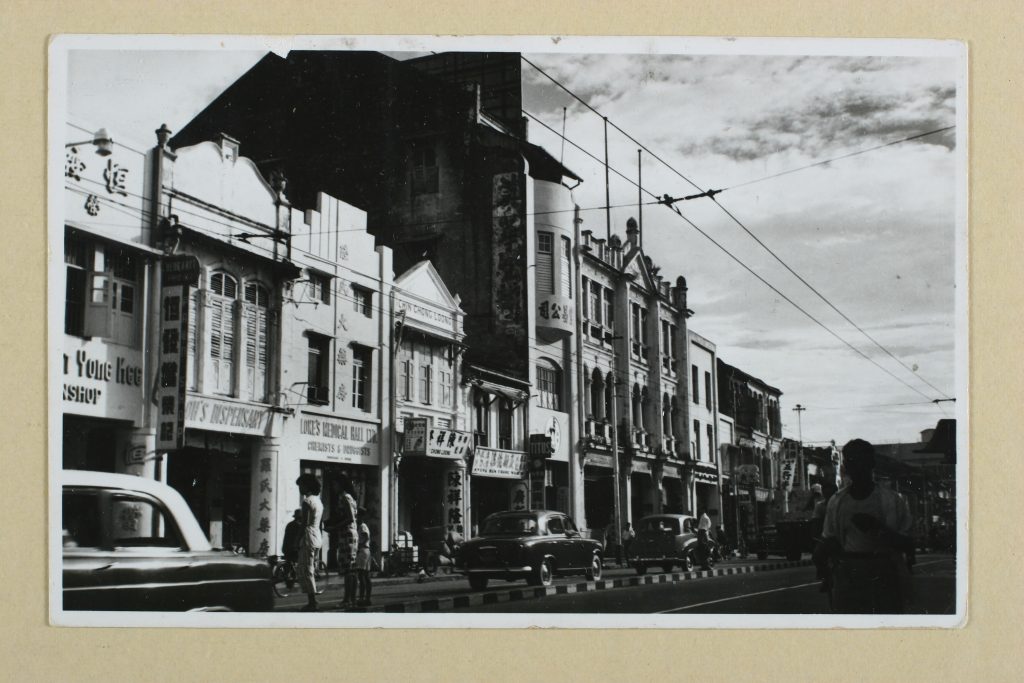

Indeed, during the 19th century, TCM institutions, medical halls, and clan centres started to be established by rich Chinese merchants all across the Straits Settlements (namely, Singapore, Malacca, Penang, and Dinding [now part of Perak]) to help poor immigrants. Eventually, these TCM institutions grew so numerous that they formed the backbone of each country’s healthcare system.

After the consultation, patients would receive a prescription for medicine which they could obtain at TCM medical halls (medical consultations and dispensations were separate at that time). These medical halls were essentially some of the first stand-alone pharmacies to be set up in Singapore, and were located near the homes of immigrants. For example, Eu Yan Sang’s first shop was at South Bridge Road, just a street away from the shophouses at Sago Lane.

Among the most commonly prescribed medicine at that time were Axe Oil, Tiger Balm, and Ning Sun pills. All of them helped to combat symptoms of overworking. (No surprise why these treatments remain popular today.)

Even if patients could not afford to pay for consultations and medication at other clinics or pharmacies (which may charge a nominal sum), they could rely on their fellow clansmen in Singapore. Coolies and immigrants would chip in what little savings they had to help cover the expenses of any member who was sick, even if they were not related. For a rickshaw man who earns an average of $20 a month—of which three-quarters went to food (just rice and vegetables) and rent— this was an immensely generous gesture.

For instance, Warren describes how Tan Moey Teng, a rickshaw puller, “gave 10 cents daily to an elderly clansman, Tan Eng Song, to help him over the toil of the last years”; when Lee Tien, who “had no kindred in Singapore”, fell ill, his clansmen “gave him medicine regularly and arranged his funeral … when he died”.

As more women emigrated from China, more families started to be established in Singapore. The increasing number of births meant that infant-related ailments were a growing concern in the early 1900s. Prenatal and natal care were still in their infancy then, so TCM stepped up to the role of providing medical aid to expecting parents and their babies.

Two TCM formulations, in particular, stand out: Bak Foong pills—which comprised Chinese ginseng, deer antlers, black-bone chicken, and other herbs—are known to combat fatigue, anaemia, menstrual pain; and Bo Ying Compound, which contains pearl and amber, and helps to reduce phlegm in infants.

Through loneliness and hardship, the early Chinese immigrants of Singapore developed bonds that kept each other, and a millennia-old tradition of medicine, alive on a tiny island far away from their hometowns in China.

TCM, in contrast to these developments, seemed like an outdated, mom-and-pop small enterprise resistant to innovation and progress. Such a perception would not be wrong, honestly speaking. TCM formulation at that time was limited to raw or ground herbs and liquid concoctions. These preparations faced issues with consistency, safety, convenience, and precision in dosage control—things which the public, exposed to Western medication, expected from any medicine.

Yet, even today, Singaporeans are relying on TCM to alleviate their troubles. According to David Tang, Chairman of Singapore Traditional Chinese Medicine Organisations Committee, “about 76 per cent of the population has used complementary alternative medicine”, a number corroborated by the scientific paper “Complementary and alternative medicine use in multiracial Singapore”.

How did TCM continue to remain relevant at a time when many were predicting its demise?

Simply put: the TCM industry read the prevailing winds and modernised TCM to meet the evolving demands of the population.

One modern breakthrough is the technology of granulating TCM products. By turning traditional herbs into granules, TCM is not only more palatable to the modern consumer, it is also safer, more shelf-stable, and portable.

TCM education in Singapore is also at the forefront of the field. For example, formalised TCM education began in 1953 with the establishment of Singapore College of Traditional Medicine, years before any such curriculum was designed in China. Today, universities like Nanyang Technological University offer a double degree programme in Biomedical Sciences and TCM.

Additional TCM products that Eu Yan Sang has developed include: ginseng tea bags (which reduce hours of brewing to minutes of steeping); convenient pre-packed TCM soup formula; and bottled bird’s nest of a higher quality and free from stabilisers (adding stabiliser, a practice common among most bird’s nest brands, gives the impression of a higher content of bird’s nest in the bottle). All these products were introduced back in the 1990s, before most TCM companies thought to modernise their products.

Eu Yan Sang has also partnered other organisations, such as NUS School of Medicine and Parkway Cancer Centre, to publish two scientific papers that explain the interactions between TCM and commonly used western medicine.

These innovations encapsulate Eu Yan Sang’s focus on catering to the needs of the Singaporeans: a demand for scientifically proven safety and efficacy, comparable to that of Western medicine, in the preparation of TCM, and treating the conditions endemic to Singapore’s fast-paced society and aging population.

The fact that TCM is increasingly being embraced by people who live in a country that boasts the world’s most acclaimed healthcare system and the longest life expectancy at 84.8 years speaks of the important role it plays in society. TCM, to many, is not just a form of medicine that maintains health or improves quality of life, but a part of culture, history, and kinship.

Indeed, neither we nor Singapore might be here today if not for the role TCM played in Singapore’s colonial days, when medical care was scarce, and jobs could literally kill you.

“A Short History of a Long Tradition: The Resilience of Chinese medicine in Singapore”, Daniel Foo Say Liang

Caring For Our People: 50 Years of Healthcare in Singapore, Ministry of Health

Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment, Brenda S. A. Yeoh

Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore, 1880-1940, James Francis Warren

The Eu Yan Sang Way: Renewing A Century of Heritage, William Koh

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram. If you have a lead for a story, feedback on our work, or just want to say hi, you can also email us at community@ricemedia.co.