All images by Cheryl Tang and Zachary Tang.

She expects to be chided for the strands of her curly hair strewn on the floor, on her bedsheets, around the kitchen, in the living room, and basically, every corner in her house.

And every 30 September, when she slips her hand under her pillow, she knows she will grasp at a rectangular packet. Like clockwork, the standard birthday angbao her grandmother gives her every year will be right there between her cool sheets.

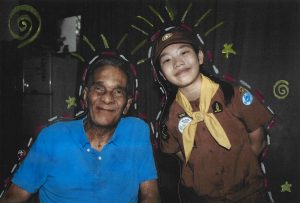

One day, this too will pass. But right now, Mdm Yong Oi Moh, her 71-year-old grandmother, is still around to remind her granddaughter not to eat too late at night, scold her for being messy, and leave her the customary birthday gift.

Moreover, living with your best friend all your life can make the miniscule details about them become exceedingly significant, from their easy gait to their vocal tics.

And if Karmen’s humble abode is anything to go by, Mdm Yong’s presence will likely always be felt.

Living solely with her grandmother, the 27-year-old walks me through her “Muji-esque” interior, pointing out “grandma aesthetic and accents” that indicate her grandmother’s unfettered influence. For instance, amongst the spartan crockery, there are a couple of mugs adorned with badly drawn cartoon characters—the kind you’d find in a heartland discount store.

Perched atop the sofa in the living room, Karmen’s three soft toys are wrapped in plastic packaging. Forget aesthetic, her grandmother just doesn’t want them collecting dust. The matriarch of the house is also “OCD” about having “everything put back in their right place”, unlike Karmen’s more laidback nature.

Above all, her grandmother demands perfect cleanliness, specifically for Karmen to immediately clean up any strand of hair shed.

But they’re all each other has: Karmen’s mother moved out of home four years ago, and her father lives in Hong Kong. So love—and co-habitation—requires them to “meet in the middle”.

It requires acceptance—not so much agreement. It doesn’t stem from resignation nor resentment, but from genuinely embracing one another’s harmless imperfections.

This is how it looks: Karmen continues to surprise her grandmother from the back with a hug when she’s washing dishes, despite knowing her grandmother doesn’t like people to hug her for fear of getting dirty.

On the other hand, Mdm Yong has no intention of relaxing her strict standards, which translates into her stubbornness in living life within tediously frugal and conservative means. She doesn’t allow Karmen to have tattoos or dyed hair, which Karmen insists “constraints [her] freedom”. As a compromise, Karmen has gotten a temporary jagua tattoo instead.

While these extreme behaviours might be frustrating to anyone else, compromise means allowing for inconsequential concessions in the grand scheme of things. For example, if this means understanding that her grandmother may chastise her for occasionally wearing makeup because she doesn’t believe in vanity, then Karmen is willing to accept the ‘criticism’.

The singular aspect that Karmen appears unwilling to budge is finding a husband and having kids soon.

Judging by the number of times Mdm Yong brings this up in conversation, neither is she.

In fact, the friendship probably began the day that Mdm Yong laid eyes on her granddaughter when she was born.

Since Karmen’s mother was 10, her mother (i.e. Mdm Yong) has raised the entire family on her own in poverty. The only ‘silver lining’ was being forced to learn financial prudence at a young age, which explains her thriftiness and practicality.

In turn, these qualities have rubbed off on Karmen, who’s since inspired to start saving more. At 27, she has started planning for her future and buying her own insurance plans, while remembering to heed her grandmother’s advice to save her CPF monies .

“From young, my grandma reminds me that the government has been topping up her CPF. She also saves bit by bit, in order to have money for retirement and travel,” explains Karmen.

The financial freedom is most obvious on trips with her grandmother to the hospital, when MediSave helps to offset the elderly woman’s medical bills greatly. During her recent cataract surgery, Karmen “shrieked internally” when she saw the sum reflected on the bill, but felt sheer relief when she realised a huge portion of the final bill would be subsidised and paid for using MediSave and MediShield Life in the end.

“This particular relief extends to all polyclinic visits with her too. Sometimes I’d translate her mail for her and realise plenty of stuff could be deducted via MediSave,” she adds.

“I know that if I were in her position, I wouldn’t be so sacrificial. She puts others before herself a lot more. But then she’d spin her own narrative and tell herself certain things are not important, and not to indulge, even when she has the disposable income,” she says.

Yet, because CPF provides Mdm Yong with some retirement income, Karmen gets peace of mind knowing she doesn’t absolutely have to financially support her prudent grandmother. This frees up her time and energy to focus on actually spending time with her grandmother, from travelling to new countries (one of their shared hobbies) to taking walks around the MacPherson neighbourhood.

In the end, Mdm Yong’s CPF might give her money, but Karmen is the real beneficiary of its true gift: the privilege of unadulterated time with her.

“Yes,” Mdm Yong replies to her granddaughter in mandarin without missing a beat. “But I wish you’d find a husband.”

Despite the mischief inherent in their interaction, no matter the topic, their intergenerational friendship transcends the bond that many of us have with our closest friends. Ironically, their playfulness compels them to stay present, lending depth to what could turn into an otherwise serious and bleak relationship, just like joy gives meaning to melancholy and the limits of time make longevity more valuable.

When your best friend is 44 years older, love is often displayed through acts of service—a bowl of cut fruit in the fridge waiting every day, reminders to pick up after yourself when you shed hair around the house, and a birthday angbao under your pillow without fail every year. Love is, then, also realising that the inevitable absence of these actions will be the most powerful reminder of its presence once upon a time. And just like this paradox of love, time is only truly treasured when you realise there can never be enough.

In the meantime, there is still time, and there are still fruits to be cut.