“My favourite book here, so far, is Ponti,” she says.

“I went for Sharlene’s talk. It convinced me to buy the book, and I’m glad I did. Really feels authentically Singaporean.”

She had not been in Singapore for more than a week.

Sharlene Teo, the UK-based author of the Singaporean novel Ponti, was one of the panellists at SWF, and her title was flying off the shelves of the festival’s bookstore. Ponti’s portrait of Singapore is rich and dripping with detail, but I couldn’t help but wonder if it was a little too …. English.

“No, no,” I argue, “This is Singaporean.”

On my phone, I pull up a page of Gwee Li Sui’s Spiaking Singlish, the first (and to my knowledge, only) book written entirely in Singlish. After scanning a few lines, my new friend’s nose wrinkles.

“This is Singaporean? This is unreadable!

After more than thirty years of trying to dismantle our native dialect, it seems that the government has been forced out of the ring, with the Speak Good English movement lying KO’d on the floor with nary a whimper.

Yet, even as Singaporean (Singlish-speaking) books and films continue to receive international acclaim, something is missing from the local portrayal of English’s illegitimate son.

That’s the opinion of the bastard’s favourite unker, Dr Gwee Li Sui.

“There are some artists that quite happily use the words, the phrases, [but] not in context. It doesn’t really show that this is part of a linguistic form. It’s just a way of turning the words into symbols, turning the phrases into commodities.”

Gwee is, of course, a respected authority on Singlish, having both the academic chops and siao unker mannerism that are essential to any purported expert.

But what does he mean by a ‘linguistic form’? Speaking Singlish is surely but a matter of swapping out some England for Hokkien, some England for broken England, and adding a few Melayu exclamations to your typical ang moh speech?

Gwee disagrees: “Singlish is not just words, it’s also syntax.”

He says that a classic error when writing with the former attitude is the placement of commas before exclamatives like lah or lor.

“When you put that [comma], you are suggesting that lah is an exclamation, an idiosyncrasy of speech that is independent of the sentence … It’s wrong! The lah actually modifies the whole sentence … so to put a comma there is not right. You’re trying to suggest you can make sense of the sentence without that particle, which is not true.”

If Singlish were really just a matter of tacking on some meaningless words, anyone would be able to read it. Gwee explains that he’s seen many people who struggle with Singlish, especially if they are not familiar with its unique structure. That’s why writing more Singlish is so important.

“The point is to move them away from this [view], show them that Singlish is more developed than … just a pidgin language, just [for] people with limited English.”

Gwee says that he enjoys reading Singlish from older books because the similarities with modern Singlish are apparent, but one can also ‘read the differences’.

“The words, the way of speech; it changes, with time … [But] there’s something that still holds, and it will be interesting to see whether we carry on like that.”

For example, the word ‘revert’, used to mean ‘reply’, was once considered erroneous in standard English. If the OED is consulted today, however, using ‘revert’ in this context is noted as a correct use of the word, originating from English spoken in India.

“They are very alert to new words that are being used in different places, and they try to absorb it into the OED. Purists are horrified,” he remarks, with not a little Gwee-ish glee.

English has prevailed as the global language precisely because it absorbs rather than rejects whatever it comes into contact with—a trait it shares with Singlish. Singlish, however, is much more advanced in this respect, co-opting not only the words but also the structure of its influences.

“You can see Singlish as a microcosm of what a future, inclusive language would be,” says Gwee.

In fact, we may be approaching a future in which standard English, as it’s currently understood by purists, is struggling to keep up with Singlish.

“In several hundred years,” says Gwee, “English … the global language … is not going to sound like how it sounds now, just like how it didn’t sound this way a century ago. For English to survive, it has to become more like Singlish, and given its history, it will.”

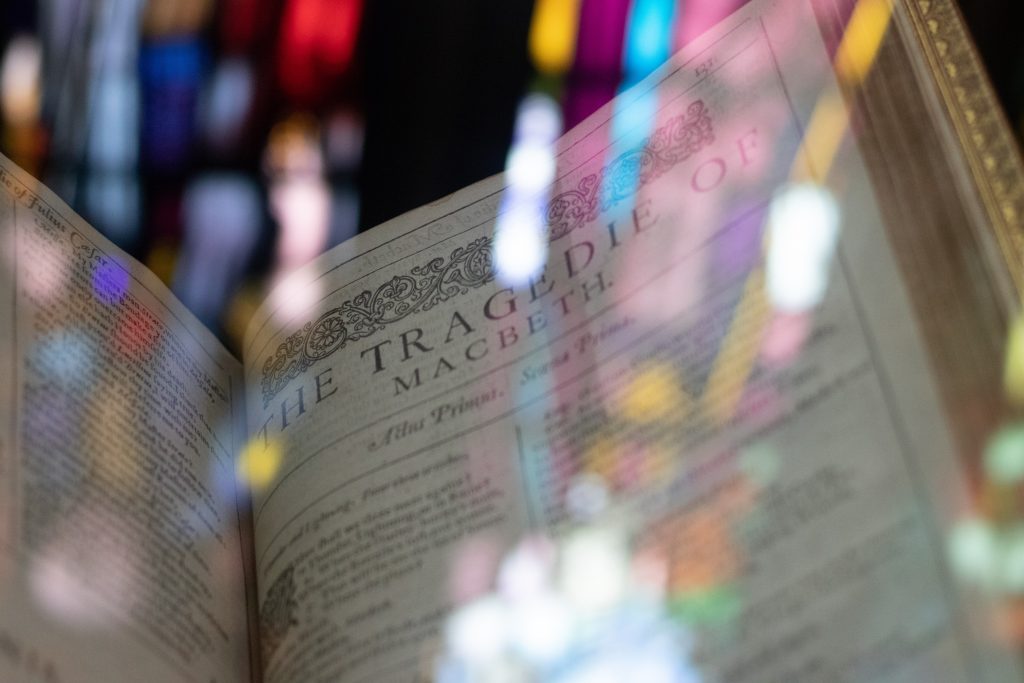

Eventually, even Ponti, with all its local flavour, will be read by Singaporeans the same way Britons read Shakespeare—gold, but old, and relatively unintelligible to boot.

“At some point,” Gwee says, “Singlish and English will merge. The future is English, but the future is really Singlish; or Singlish as a big part of English.”

“Chinese are the majority. Increasingly if you notice, Singlish is getting more and more Hokkien words, and people are forgetting that there are actually equivalents in Malay that we previously used to speak, then we stopped using … I don’t think that’s a good thing. It makes Singlish into something … less diverse.”

“We must not lose the reality of speakers. [Singlish] … is a way for us to remember that we are living in a diverse society,” says Gwee.

It’s a stark contrast from what the government considers diversity—clearly outlined racial boundaries and a social policy to match. Singlish, as it organically meshes its various source languages together, is both a symbol of and a medium for the deeper diversity that exists in Singapore; an inextricable cross-cultural weave.

You can pick out the threads, trace the colours, but it’s only when you take a step back that you can see the full picture. Singlish is the Singaporean identity made manifest, an earthly answer to that existential question: who are we?

Gwee is not just pushing diversity for diversity’s sake, however. Remembering Singlish’s multicultural roots does much to enrich the quality and depth of the language.

“I don’t think we should dis-educate ourselves, devolve that knowledge, or forget it; all these words that we used to have … Look at ‘buay tahan’ versus ‘tak boleh tahan’ (buay is Hokkien for cannot, tak boleh is Malay for the same). They are synonyms, but … one means something slightly different than the other.”

Developing the shades of meaning and the emotional range of Singlish is the first step in advancing the language. The second: widening the range of environments and contexts in which it is used.

Gwee explains that, to many Singaporeans, Singlish is perceived as ‘common speech’; used to order food, or in a joking conversation, but not in thoughtful, intellectual dialogue.

This was what motivated him to write Spiaking Singlish, a non-fiction guide to the language, written entirely in Singlish. While the book is very funny, it’s not all comedy; that was where the challenge lay in writing it. In trying to find a more serious tone for Singlish, Gwee feels that he was in his own way trying to introduce the language to a more profound plane of discourse.

While not all artists share his sentiments on the importance writing in Singlish, Gwee explains the significance of seeing your native tongue represented: “It’s the affirmation of a certain ‘aspect’ of yourself that you are taught not to give too much weight to.”

Perhaps this unidentifiable, amorphous ‘aspect’ is what makes us uniquely Singaporean, and all the Bicentennial messaging or CMIO-demarcations in the world can’t do a thing about it.

We are not four separate slices of a pie chart, we are a complete whole; our language is not a cleanly separated and controlled school program, but a coffee-shop potpourri of varied speech.

Singlish, weaving between languages, cultures, and tradition, dodging the hooks and jabs of the Powers That Be, is about denying authority, not conforming to it. When the institutional resistance, demonisation, and stigma fade, Singlish will be the last fighter standing, because it holds the key to our past—and may unlock our future.