All images by Khaliq Masuri

1. Going on an overseas trip with your child to reward him or her for working hard during the academic year

2. Doing a massive spring cleaning and getting rid of the 7000 assessment books your forced your child to complete.

If you fall under the second category, the odds are that you’ve contributed to this insanity:

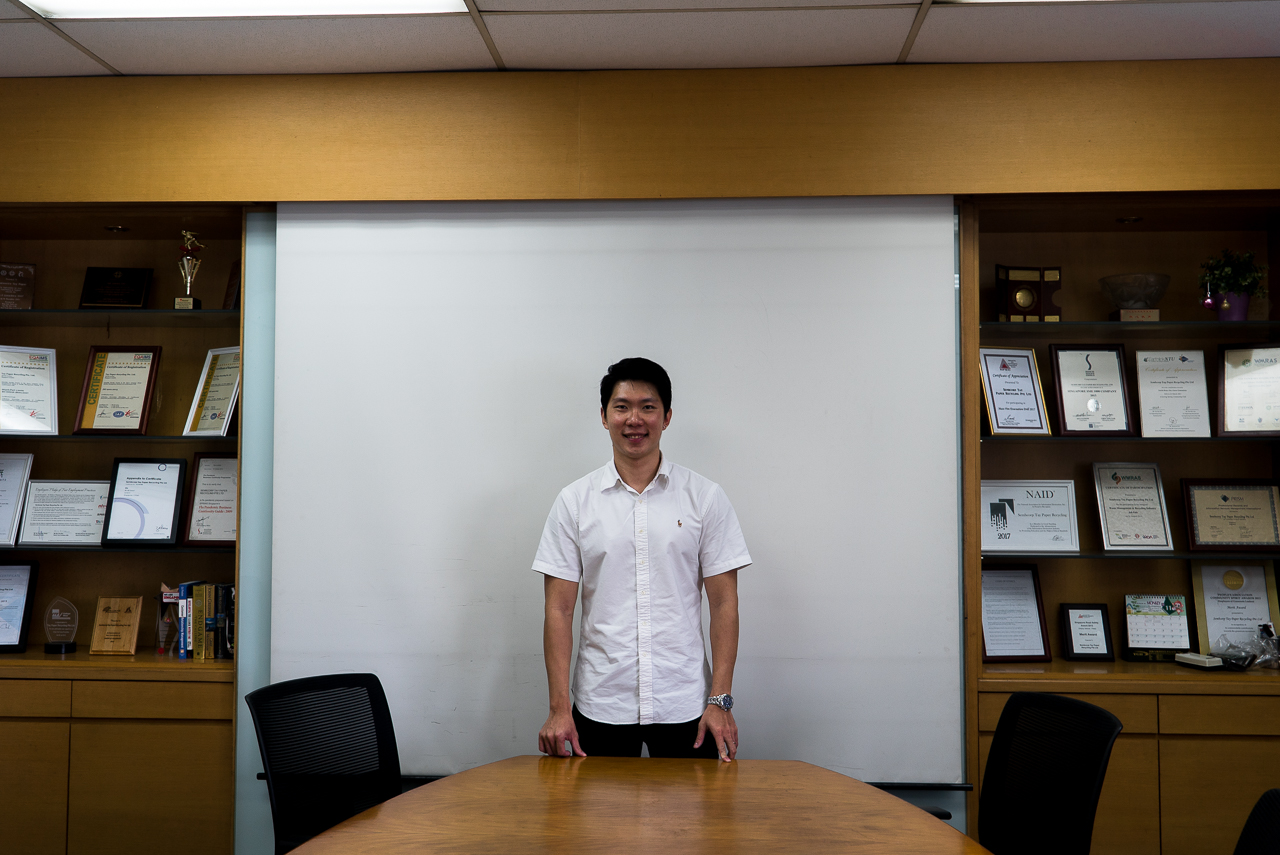

Tay Paper is one of the market leaders in the recycling sector, and they have almost 30 years of experience, having incorporated the company in 1989. Prior to this, they had already been in the recycling business for twenty years.

Andrew Tay, head of Business Development, is in charge of the privately owned company which exports about 4000 tonnes of paper every month. They have come a long way since his grandfather was a humble karang guni man.

As part of this operation, vans from Tay Paper visit companies with mobile shredders, shredding documents in the presence of clients. These documents can often weigh a few hundred kilograms, especially in industries that are heavy on paper usage. Most of their regular clients include auditing firms, banks, and law firms.

“Most of the bigger companies come to us weekly or bi-weekly, but some come to us for their annual spring cleaning.”

This entire process takes 15-20 minutes, and after the shredding is complete, a certificate is presented to the client, and an efficiency report is sent to them to let them know how much paper or how many trees they saved.

“Companies like to put these green features into their financial reports as part of their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility),” Andrew tells me.

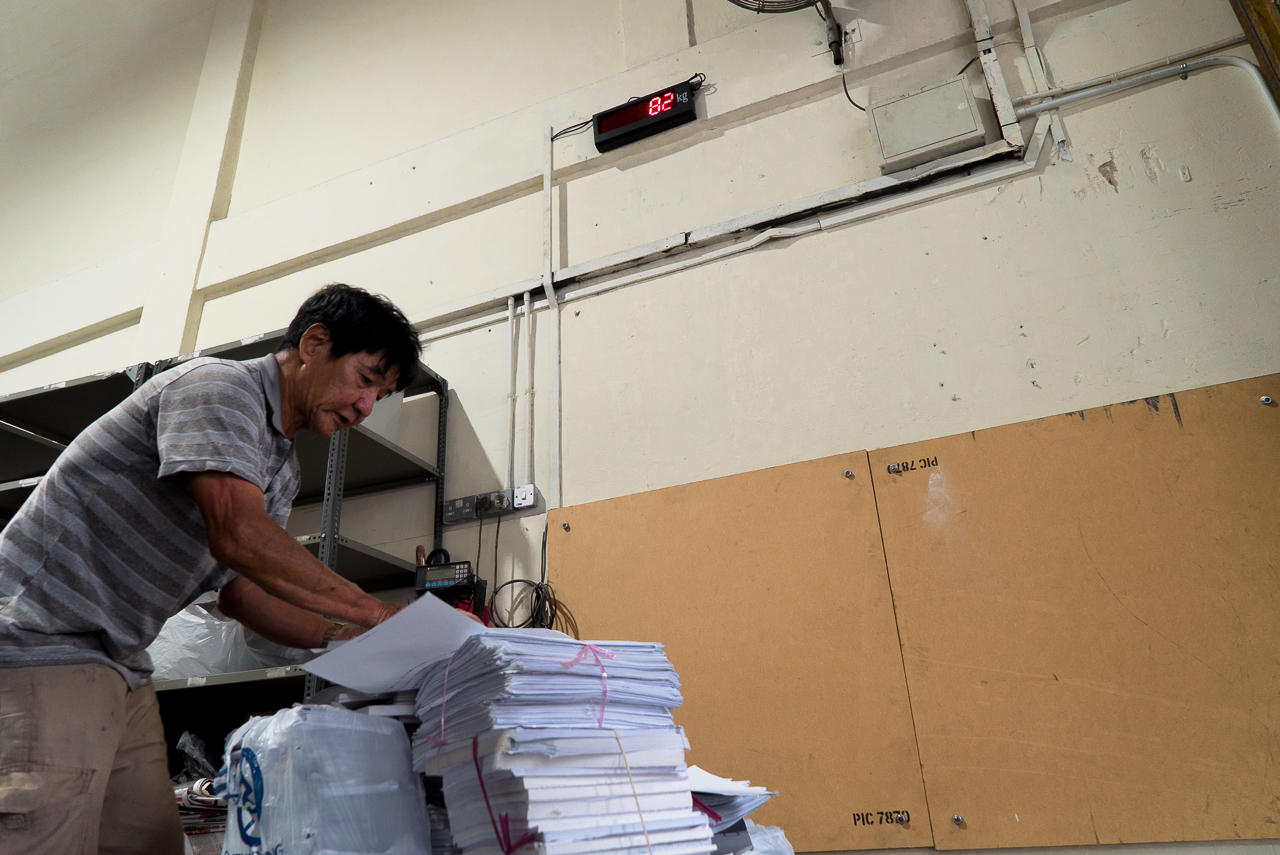

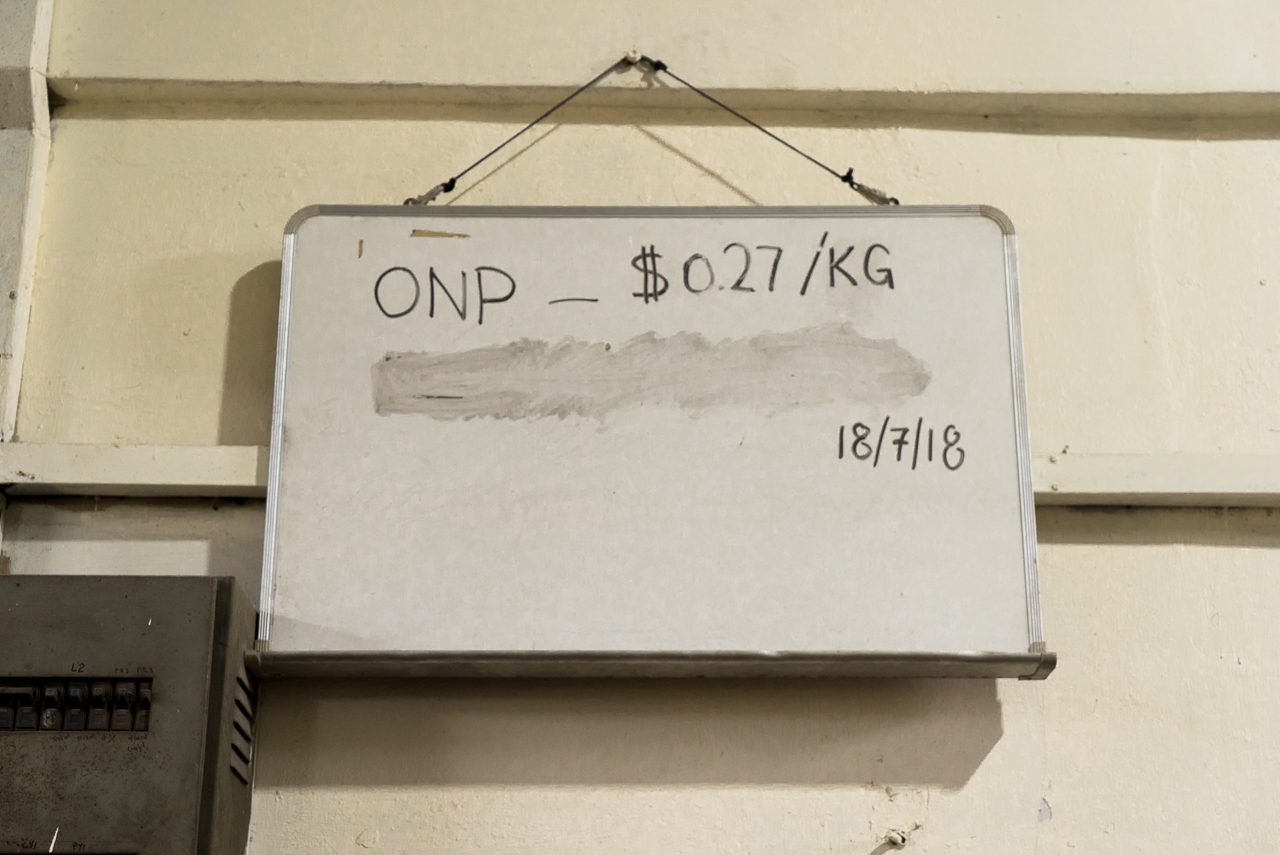

Aside from these companies, Tay Paper also relies on the everyday karang guni man for their supply of paper-based recyclables such as cardboard, old newspapers, and regular paper.

Each day, up to 3 tonnes is collected.

“Some of these aunties are over 80 years old, but they can collect almost 200 kg of cardboard everyday, push it on their carts all the way here and sell it to us,” Kenneth, Sales Manager at Tay Paper, tells me.

It is not an easy life, but for collecting cardboard from 4am till 9am, these women can sometimes make around $50 or $60 each day. And they do this everyday, without fail.

Traditional Karang Gunis like 65-year old Mr Tan are able to bring in more because he has a truck to drive around and carry his load. However, this is a double-edged sword as the miscellaneous costs associated with owning and driving a vehicle in Singapore can add up, taking away from his humble earnings.

“There was a shipment of recyclable paper which had Milo powder in it today,” Dominic explained. According to him, a different smell permeates the paper mill each day, and it ranges from good to bad.

“Sometimes, we get cardboard from the wet market, then the whole place will end up smelling like fish. Then during Chinese New Year, the whole place will smell like mandarin oranges, cause that is the time when we will get all the boxes that hold the oranges,” he adds.

I know. Before I went to the mill, I too assumed that there was only one kind of paper.

“It is practically a vacuum inside. There is no light and because it cannot be reopened, you hear those stories about illegal immigrants hiding in containers to get somewhere. But because there is no air, some of them are dead by the time the ship reaches the port,” Dominic quips.

During the tour, I ask Dominic if he thinks Singaporeans do enough to recycle.

“If you go to places like Japan and Taiwan, people carry plastic bags around just so they can throw their rubbish, which is why you hardly see dust bins around.”

He continues, “When I was in Japan, I noticed that even at home, everyone separated their recyclables by the category, meaning the plastics went in one bag while paper went in the other. Here, everything is just thrown into one, which means that the additional step of sorting has to be taken.”

In Singapore at least, there is definitely room for better infrastructure and the cultural shifts needed to ensure that recycling becomes a more seamless process. Yet I can’t help but wonder about the livelihoods of people like Mr Tan and the old women whose lives depend on the cardboard they collect every single day.

If we truly excelled at recycling, what would happen to them?

Perhaps there is a reason why things work the way they do, and some things might be better left untouched.

ps: In case you were wondering, yes, I saved that LKY book.