A few years ago, I owned a pair of black monk straps from Topshop. I still think about them with a fondness typically reserved for a loved one who has passed on.

Not to be melodramatic, but no other pair of shoes has been able to compete with its sheer comfort and sleek design, and neither has any taken its place in my heart. I paired those shoes with every outfit, wearing them everywhere for about a year, until the soles wore thin. Finally, a growing hole in my right sole prompted a trip to the cobbler.

To date, I still distinctly remember the elderly cobbler regarding me with curiosity reserved for the most incredulous situations. Gingerly pulling my tattered shoes out of the paper bag, he remarked, “Girl ah, just buy new shoes lah. This one cost more to repair.”

Then he went back to shining the shoes he was working on, leaving me grasping at him to reconsider his decision.

There I stood, a grown woman in her mid-20s then, on the verge of tears in a freaking shopping mall. All because I couldn’t get my favourite pair of shoes repaired.

“But, but, uncle, I don’t mind paying! Can you try?”

“Not worth it lah.”

He promptly waved me away, dismissing both my profound sentimental attachment and the impracticality of repairing a broken item.

Trust me when I say this: I’d never known heartache or resentment until that moment. I knew then that these were not shoes I would find again.

Eventually, I did what every Singaporean usually does with old or broken items, sentimental value be damned. I threw them away.

This behaviour repeated like clockwork until I became too horrified to continue looking. It may be unreasonable to expect everyone to be conscious of their behaviour all the time, but surely using more than one plastic plate per person for a single meal isn’t just excessive—it’s outright unnecessary.

Yet this ‘throwaway’ culture, especially noticeable in our consumption of single-use plastics, is nothing new. And if the story of my shoes was any indication, our tendencies to dispose anything that no longer serves its purpose seems to translate into other items in our lives.

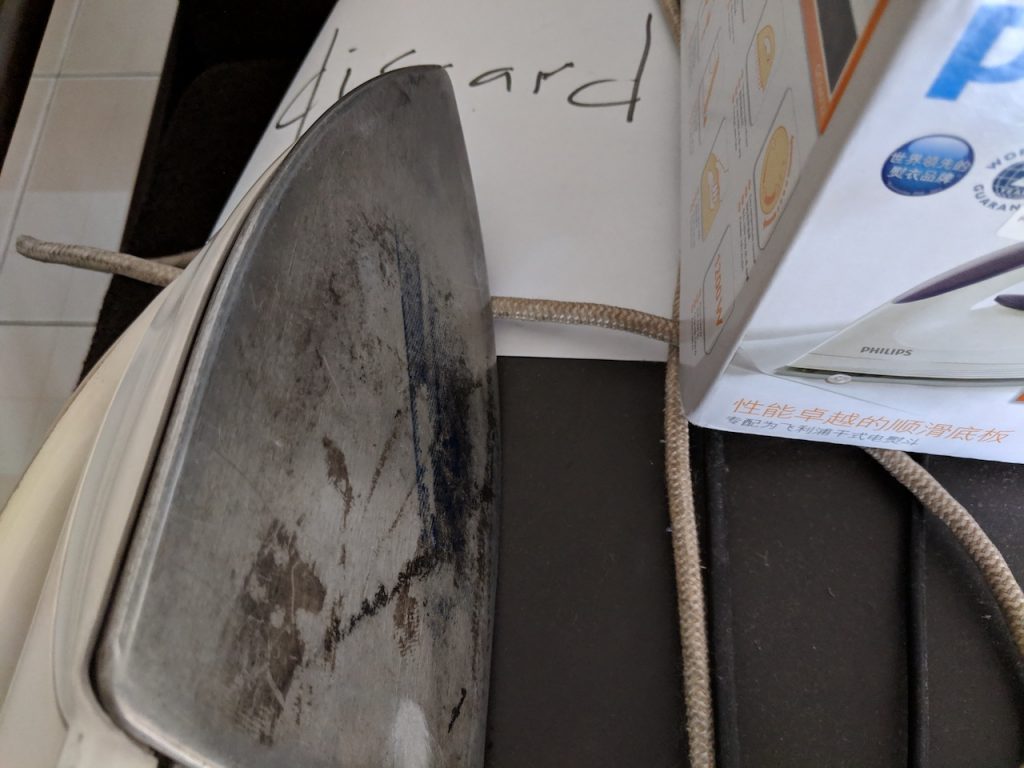

So when I chance upon Repair Kopitiam, an initiative conceived to combat Singapore’s buy-and-throw away culture, and get people to consider repairing first before throwing away their broken items, I decide to find out where the lack of a ‘repair mindset’ in Singaporeans stems from.

Speaking with their co-founder, Farah, she explains that many Singaporeans she’s met have in fact been “accepting and appreciating the idea of repair”.

Because the barrier to repairing is pretty low, Repair Kopitiam believes this is one of the best ways to tackle waste issues in Singapore, particularly because the action of repairing is intuitive and does not require one to have a ‘green’ mindset. Because repairing usually doesn’t require a mammoth effort, it also teaches individuals that tiny actions can make a difference.

Farah walks the talk by sharing how she recently repaired her frayed shirt cuffs. Like her, anyone who’s successfully repaired or restored something of sentimental value can attest to the sheer joy of rediscovering a second life for a beloved item thought to be gone for good.

However, Anne posits that many Singaporeans adopt the ‘buy and throw’ mentality because of our online shopping habits. We don’t really ‘see’ our purchases as we’re clicking and buying, so we don’t feel like our money is spent. After awhile, mindless consumerism becomes second nature.

But as much as she’s inclined to repair old items, Anne admits she’s also been penny wise, pound foolish when it came to repairing her old laptop. She remembers spending almost the same amount to fix it as it would cost to get a new model.

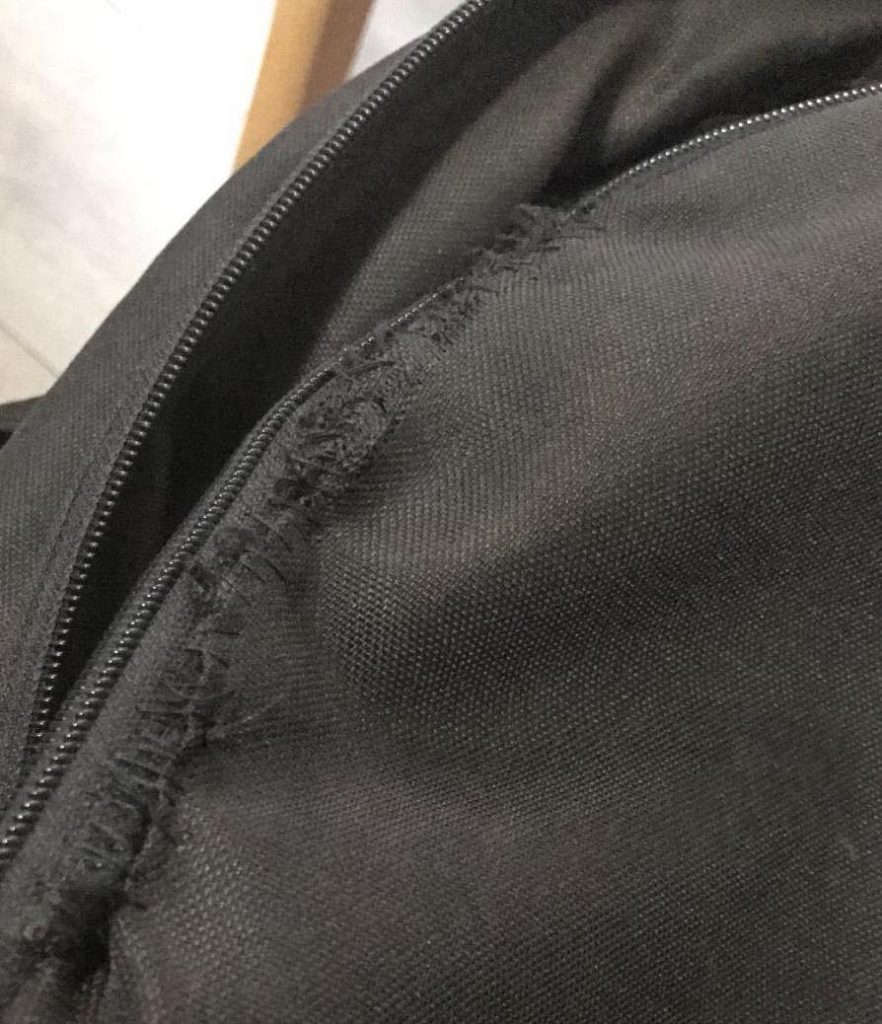

Another friend, Pamela, recently repaired a faulty Decathlon backpack that would only cost her less than $4 to get from the store. Nonetheless, the 23-year-old took a needle and thread to patch the hole in her bag, so she wouldn’t end up buying a new, unnecessary one to add to her clutter and waste.

“My bag is black, so the seam isn’t very noticeable. I was able to give a ‘spoiled’ item new life by spending zero dollars and 10 minutes repairing it.”

Pamela’s thriftiness even extends to technology. When she recently needed a new MacBook charger, which would cost $108, she tried seeking the help of a repairman and even looked for someone with a spare charger lying around.

As for her MacBook Pro, which has gotten sluggish after five years, she’s happy to “upgrade the drive for less money” than it would cost to buy a new laptop. Even so, it strikes me that most people would choose to save themselves the hassle of spending a few hundreds on such a potentially futile endeavour.

“I remember my favourite pair of sandals were a bit worn out, so I bought super glue to glue the cracks in the sole. Recently when I wanted to replace the bottom sole and the top straps, I realised the strap was beyond repair. Still, I did everything I could to keep them because the design is so lovely,” she shares.

Even though Jane already has a replacement, she still hoards the old pair in her shoe rack for—you guessed it—sentimental value.

On the other hand, 61-year-old Joseph informs me that he used to pick up items that his neighbours left at the void deck of his HDB flat, because they were “still good and they were free”.

He jokes, “I’m not very Chinese, I guess. Most are superstitious about using things that others owned.”

Joseph is so thrifty that he’d try to patch his old clothes himself; if his workmanship makes the clothes look worse, he’d keep the shirts for home use. In fact, most of his work shirts are gifts from friends.

Besides clothes, he has also recently repaired his rice cooker by using his hand to “trip the control to get it to still cook” after the control cover got dislodged. Even the standing fan in his room received an overhaul after he managed to find a blade at the void deck to replace one of the faulty ones, since the brand didn’t sell spare parts.

Both Jane and Joseph can’t remember a time when they didn’t practise environmentally friendly measures, from lining the rubbish bins with newspapers to opting for actual plates over single-use plastic plates at barbecues. Yet their actions have always felt so natural that they don’t consciously drill an eco-friendly lifestyle into their own families.

They simply hope that their children have learnt how to be better citizens and human beings by observing their parents.

Rather, most things that need replacing are affordable and readily available at the click of a button, so it’s hard to understand both the concept of scarcity and the larger impact our consumption habits have on the planet. This inevitably enables mindless consumption of single-use plastics and the disposal of old or broken items that could still be spruced up.

If repairing were indeed the gateway to adopting more mindful usage of single-use plastics and other harmful material, then it might be an uphill battle. After all, I doubt that pragmatic Singaporeans have the time or patience to make repairing a habit.

Thus far, I’m all for Pamela’s solution to getting people onboard a ‘zero waste lifestyle’, where she believes even small, individual actions add up to creating a sustainable future for Singapore.

She explains, “I think having zero waste or being eco-friendly should actually be driven by private interest. Reducing waste should also help my health, allow me to live better, and save me money. Hopefully this helps people appreciate ‘eco-acts’ better and find their own intrinsic motivation to act better.”

In the end, the way we choose to live impacts our planet, which in turn comes back to affect our life. Everything comes full circle.

Just like how this year, I met someone who owned two pairs of the exact monk straps I had thrown away years ago. When I asked her why she bought two at the start, she said she loved them so much, so she wanted a backup pair in case she couldn’t find anyone to fix the pair that would be the first to fall apart.

Pledge your commitment to #RecycleMoreWasteLess here.