Photography by Thaddeus J Loh.

As a child, Maria “Masha” Isaeva was plagued with skin rashes. They were so bad her skin would become flakey, red, and itchy to the point that she couldn’t sleep. Her doctors told her she couldn’t eat anything but potatoes—anything else would cause an allergic reaction. By the time she was 12, she was so underweight that her apartment elevator wouldn’t detect her presence when she was alone in the lift, making her unable to travel in it.

Desperate for a resolution, her mother booked them a flight from Vladivostok, their hometown, to Singapore, where Masha’s Japanese stepfather was residing (she refers to him as her Otousan, which means father).

Soon, with the help of Singaporean doctors and the tropical climate, her body changed. The red rashes on her skin started fading away, and she was allowed to eat an assortment of food for the first time—like strawberries, chocolate, and anything containing milk. She would rarely ever get flare-ups again—until recently.

Red patches have reappeared on her skin. The cause? The stress of moving from Singapore in a matter of days. After 17 years, Masha’s visa is still tied to her employment. And when most of the foreigners in her company were trimmed, she decided to leave—following the exodus of almost 200,000 other foreigners who left in 2020 alone.

10 days To Go (From Masha’s Diary)

I have made a list in a day of who I can meet for the last time

in my last 10 days in Singapore.

It’s funny having to squeeze years of memories with people

into hourly interactions.

21 May 2021

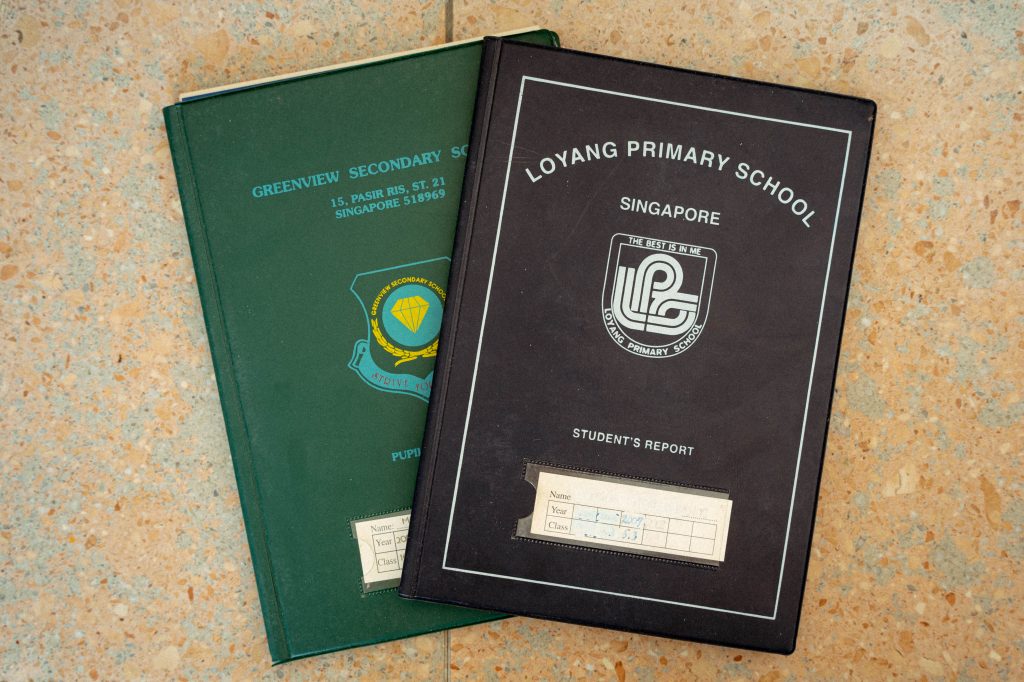

Living in Pasir Ris, Masha was assigned to Loyang Primary School from MOE, where she attended before moving on to Greenview Secondary. Integration in school was not easy at first—between the language barrier and looking obviously foreign, she was often excluded.

While she soon managed to make close friendships, it was her teachers who never warmed up to her. Soon after joining, Masha tried to join the National Police Cadet Corps (NPCC) as a CCA. She joined because she “likes discipline,” and because it was a good opportunity to learn Malay.

But when it was time for all the enrolled students to collect their uniforms, Masha’s was the only one not there. Instead of picking up the attire, she was taken into a room where she was interrogated. “They asked me, a 12-year-old, what my intentions were with joining NPCC,” she recalled. “They asked me if I intended to send my uniform abroad, and they asked me to promise not to export it.”

The conversation ended with an agreement that her uniform would be ordered in, but by National Day, it was still nowhere to be seen. “Just march without a uniform,” they told her. Unsettled, Masha dropped out.

“I told them I wasn’t going to go forth with marching on the day itself as the only person without the uniform, it’s embarrassing.”

Over her 17 years here, the system has reminded Masha time and time again that she is a foreigner. Often, when flying back from abroad when travelling, she would get questioned by authorities. “You’re too young to be working here alone, we need to check your documents,” officers would tell her. Similar to Masha, I have heard from many Russian women that they are often questioned about being escorts or prostitutes in airports across the globe.

Now again she is reminded of her standing, as she waits for the result of her 10th PR application—the previous nine of which were rejected.

9 Days

Time has a very powerful way of filtering out chaos

The noise of people you thought saw you are now silent

The people whose intentions had been a grey area

have a fixed colour palette now.

This day will become a blur too, and moving

will allow me to see things from a broader perspective,

from a lens of a person who is not weighed down

by a giant adolescent diaper.

Those who do not become a blur, will be immortalised

Are there more reasons to leave than to stay now?

22 May 2021

The last time I saw Masha before this interview was over a year ago. She told me how when we last met, I asked her a question that has remained etched in her mind ever since.

What keeps you here?

When we met again, she knew the answer, one she had thought about continuously. It’s the relationships with people.

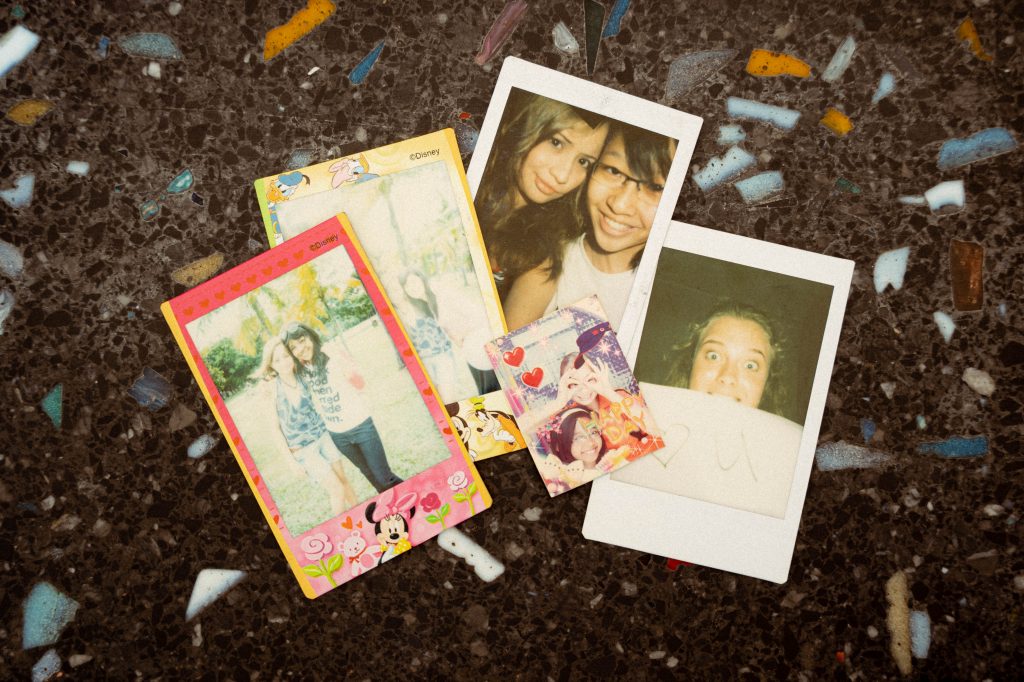

“My first love happened here. My first graduation and job too,” she said. “I watched my boyfriend go through NS while I got my diploma. I went to the funerals of my friend’s mothers. My own mother’s church friends became my second family when she left.”

“Over time, my friends have become my everything here. When I’m sick, they are the ones who send porridge to my house and bring me groceries.”

While heartwarming to hear, all of that is not recognised on paper. But while her documents say she is an immigrant, it takes barely more than 10 minutes with her to realise she is far from one. Her accent sways from intense Singlish to generic English. If you talk to her about her career as an Art Director, she can easily go on about the plans she had for Singapore’s creative community. These were so consolidated she even applied for PR via a National Arts Council scheme that rewards talents who intend to make long-term contributions to the local scene—but this attempt also failed.

6 Days

What am I feeling now? The word for this sits between the pages

of a foreign vocabulary I am yet to discover.

Like when you visit a new place for the first time, and you experience loss,

disorientation and floatiness for the first couple of days

Places I used to frequent as a student,

the parks where we would have family BBQs

or the traffic lights I would cross for daily business lunches

have become unfamiliar. It’s very uncanny.

I feel like my mind has already detached itself

from this town while my body has not.

My mind is floating somewhere,

I will find out soon when I land.

25 May

So where are you from? I asked Masha.

“I’m a citizen of the world!” she laughs with a grin on her face. “Say that.”

The second time I asked, she said she only knows that Singapore is home.

“I feel the most stable here. I feel like I belong but literally, I don’t. I thought about that over Hari Raya. My childhood friends invite me to their homes every year. I’ve seen their siblings grow up and their parents grow old, but unlike them, I don’t know if i’ll be there next year.”

While these memories float around vividly in Masha’s mind, they only exist there. There’s no tangible proof of them being there—and she knows it.

“I’m not investing in and buying property, and I’m not in cancer research or finance,” she said. “And I really like that the government is putting locals first. Every country should do that.”

But why is Masha not a local? She will never know—PR application rejections don’t come with reasoning.

Singapore has a relatively high number of foreigners living in the country, but what kind of immigrants are preferred remains unknown. On one hand, there are immigrants like Masha who are essentially locals—their relationships and lifestyle are built side by side with their Singaporean peers.

Then there are immigrants who come in with job expertise or financial prowess—your researchers, finance moguls, and shipbrokers, among many others. Naturally, the government may prefer these individuals for the knowledge and experience they bring with them.

But the same week that Masha leaves, Bloomberg announces that Singapore is the new preferred destination for the region’s ultra-rich and their families. This contrast begs one question: what will the future of integration between foreigners and locals look like?

What happens when deeply rooted foreigners are forced out, but schemes like the Global Investors Program give the ultra-rich a fast track to gaining Permanent Residency (PR)?

It is only understandable that the government would want to attract investment and talent to the country, but to what extent can these immigrants integrate into society?

Last year, a survey found that more than 6 in 10 Singaporeans felt that foreigners were not doing enough to integrate. But as the Bloomberg article highlights, the newly settled rich are currently scrambling for luxury property, sports cars, and golf club memberships—is this where bonds with everyday Singaporeans are fostered? They would need to go far beyond their comfort zones if they intend to integrate into Singapore society.

For Masha, someone who has been through the same system as the average Singaporean kid, these headlines could be a source of resentment. But Masha says she is leaving with a free heart.

“I’m not angry or sad, I’m just at a state where I’m trying to draw conclusions. After having been through so much here, there’s so much emotional baggage to sort through.”

5 days

The most interesting part of my journey will start

when I leave Singapore

People will want to know where I come from,

about my childhood, and why I’m not living there anymore after 17 years

When you’re done chewing your gum, do you spit it out?

26 May 2021

Recently I interviewed Jane, a Singaporean woman who left her insurance career, car, condo, and marriage to live a digital nomad life in Europe. One of the biggest realisations she had was that all her old dreams and aspirations were in fact not hers, but those absorbed from the society around her.

When she came to visit Singapore after a year, the joy of seeing her old family and friends was trumped by sadness, a sense of feeling out of place.

“I love Singapore, and I love my country, but if I can’t feel at home there, then where can I feel at home? I felt sad because I knew I would no longer be able to fit in,” Jane said.

When I asked Masha what the scariest part of leaving was, she said something similar. It wasn’t leaving behind people or memories, as these can always be revisited. The scariest part was leaving behind a mindset, a way of living life she may soon outgrow. You can come back to people, but you can’t revisit a life you have evolved from.

“I know once I’m out of this bubble my life will change 360,” she stipulated. “After seeing more of what life has to offer, I may not want to return, and I’m afraid of that feeling.”

“That part is scary because that means I’ll have to put this huge chunk of my life—17 years—behind for good.”

And how will Masha explain those years to new people she will meet? How do you explain to someone that you are Russian, but you feel more Singaporean, even though you can’t legally call yourself that, or live there?

Until this day, her sense of identity has been heavily tied to being in Singapore physically. But once she steps foot on that plane, 17 years of life will have only existed in her memories and of those around her. How does one reconcile that?

2 Days

“Why today so tired?” said Aunty Winnie from Cheers, who probably knows more about my everyday than the person next to me at work

Aunty Winnie works at West Coast Plaza Cheers. When she found out I was leaving, she said “can give me something from Russia one? Souvenir?”

I told her I don’t have anything from Russia as I grew up here, but I will try to think of something

“Never mind just pass me something before you leave”

I didn’t manage to catch her as she was off shift, so I passed her a letter and handmade bracelet through a colleague

“Hey i know you r leaving Singapore this week, i’m so exhausted, can I just send courier to pass me back the powerbank?”

A text from my ex-colleague and friend who’s known me for 5 years. He was like a brother to me

28 May 2021