Deftly, the 26-year-old swivels round and grins, one hand expertly guiding the right wheel of her wheelchair while the other rests in her lap.

“Why you so slow?” she responds playfully, effortlessly wheeling herself over, “Your wheels getting stuck is it?”

Just 5 minutes before this, in the open piazza outside the mall, the three of us had attempted in typical Singaporean fashion to decide what to have for dinner. Apart from the fact that both Amanda and Judy are in wheelchairs, we looked just like any other group of friends—all equally indecisive and reluctant to take responsibility for the group’s diet.

“I’ve never been here before,” I say. Which is true, and while also an obvious cop out, I’m trying not to be insensitive because I don’t know if there are particular restaurants they prefer for their accessibility.

Sensing my hesitation, Judy says, “Ok, you want to see how we decide what to eat right? Let’s go take a look.”

Following that, like many an aimless family, we go on a tour of the ground floor, discussing whether we feel like Thai food or chicken rice.

Eventually, we settle for chicken rice, after which we spend about 2 minutes choosing a table and rearranging chairs. When I return after ordering, Judy tells me, “Actually right, you should have let us order. Then you can see how we go about settling our food.”

“Not that there’s anything special about how we do it lah,” she adds, as I awkwardly mumble something about how I was just trying to be helpful.

Out of convenience, were there particular foods or dishes they ate a lot more of as compared to others? Did they have to take many different things into account when planning meals? What was something they had always wanted to cook, but were unable to because of their disabilities?

Eventually, I find out that like many other Singaporeans, they’re fortunate enough to have parents who cook for them. This, on most days, settles dinner.

Judy, who works for the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDAS), regularly eats out for lunch in the Bishan area, where MDAS is headquartered. Because they work with individuals with muscular dystrophy, she usually accompanies members, who attend regular programmes at MDAS, to buy lunch.

As for Amanda, who works in banking in the CBD, lunch is broccoli with chicken about twice a week. On other days, she gets her colleagues to ‘da bao’ for her.

When we swing by the supermarket, she lists some other things she likes: bananas, cherry tomatoes, and potatoes.

She’s careful to emphasise that she doesn’t eat this way because of her disabilities. Sure, the food is easy to prepare; she also avoids eating out during lunch because the CBD at lunch hour is basically the movie Jumanji, which any regular human being can relate to. Instead, she eats like this because she enjoys it.

But when the conversation turns to whether she has thought about how she’ll settle her meals in the event that she moves out, Judy says to her, “I don’t think you will ever move out.”

“What, why?” Amanda counters, not quite offended but nonetheless a little defensive.

“What makes you say that?”

Judy replies, “I think you’re too comfortable where you are.”

Yet when Amanda concedes, “Yeah, I think you’re right,” she doesn’t sound like someone whose physical limitations dictate her lifestyle. Rather, she sounds just like any other millennial who’s gotten a little too used to living at home.

From those who never lift a finger to help with laundry to those who don’t contribute to household expenses, she echoes the sentiments of many of my friends—especially those in their late 20s and early 30s who still live with their parents.

Later, she adds, “It’s not that I don’t want to cook, it’s just that my kitchen is not designed in such a way that’s accessible for me. Baking and all that is fine. But if I want to reach the stove, then that’s a problem.”

Inadvertently I find myself saying to Judy, “Actually, it sounds like you guys settle your meals pretty much like the rest of us do.”

“You know why?” she responds, “That’s because we do eat the same way. We’re just like normal people.”

“If there’s a place with steps or what, it helps if there’s someone who can carry me. If I need help with anything, at least there’s someone around.”

In a Straits Times article from last month, Judy took a fellow wheelchair user, who was visiting from Thailand, on a tour of Singapore’s Central Business District. The article details the challenges they face: from detours to turning back after encountering staircases without ramps, one can almost sense their frustration as they engage in what Judy calls “an adventure in getting lost”.

At the same time, Judy makes it clear to me that she considers both her and Amanda lucky because they’re both working, can afford to eat out on a regular basis, and “money is not a concern”. On top of her day job, Judy works as an accessibility consultant; she also drives, which means she can pretty much go anywhere she wants.

Yet there are also many others who lead dramatically different lives, she tells me. They aren’t able to find work, and they don’t have family members who can help them out.

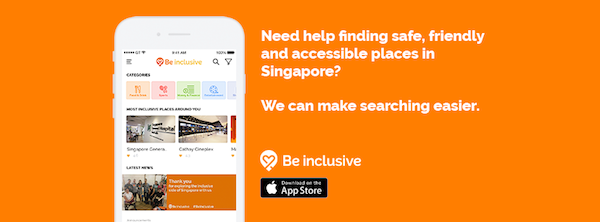

In a blog post by Be Inclusive, an app and platform that aspires to shape more inclusive cities, it is described how even “disabled-friendly” features like tables with no chairs can isolate those with disabilities—they end up forced to sit alone or with other wheelchair users, and their able-bodied companions have to sit elsewhere.

This is obviously not intentional, but one can’t deny that it’s a feature that lacks sufficient empathy.

So the point isn’t really to give these individuals food, or even money to make their lives easier. Rather, it’s about getting to a place where we instinctively take into account the needs of diverse individuals. When including everyone becomes second nature, that’s when everyone benefits, whether socially, professionally, or simply in terms of convenience.