All photography by Marisse Caine for Rice Media

After a heavy rain, the forest lights up with foxfire.

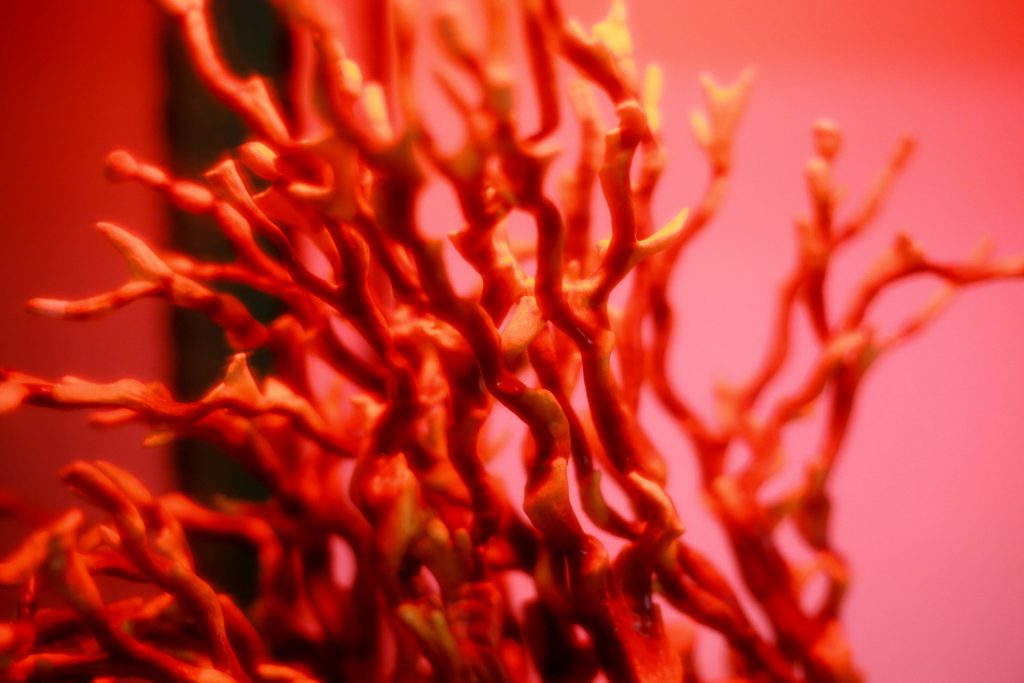

From the hillsides of Bukit Batok to the green lung of Macritchie, clusters of bioluminescent mushrooms appear seemingly from out of nowhere and all at once, like psychedelic beacons in the darkness. This phantom light draws in the critters and insects of the forest, which helps the mushroom to cast its spores across Singapore like an invisible spell.

For the average city-dweller, the mushroom feels rather alien and unnatural. It is by turns attractive and disgusting; beautiful, yet vaguely unsettling. We fear it for its poison even as many fungi like lingzhi are prized in TCM for their rare healing properties. It’s the yeast that raises our bread and the mold that spoils it.

It exists in a liminal space between the living and the dead.

As Nature’s decomposers, mushrooms break things down. They remind us of things we’d prefer not to think about—death, disease and decay—even as they facilitate the most vital parts of life.

So much about the mushroom remains shrouded in mystery. In recent years, scientists have discovered an ‘internet of fungi’, a communication network made up of fungal threads called mycelium that’s buried beneath the soil like fiber-optic cables, connecting the forest together.

Through this network, large trees can donate essential nutrients to younger seedlings in the shade. Plants can warn their neighbours against predators or disease by sending chemical signals through the mycelia.

This network has existed for thousands of years. And even as we clear our forests to make way for development, most Singaporeans remain largely ignorant of the ancient mysteries buried beneath their feet.

Which begs the question: is it the mushroom that is alien or are we as human beings just alienated from Nature?

Have You Met the Mushroom Man?

“For many years in my 20s I was just floating around in life,” says Ng Sze Kiat, 41. “I guess I was looking for something that I could dedicate myself to. Then one day, mushrooms came into the picture and I fell in love.”

This might sound like the opening monologue of a tree-hugging hippie, but a quick tour of Kiat’s lab at the heart of Bukit Merah quickly dispels this notion.

As the one-man R&D team behind Bewilder, the man knows his science. His primary occupation, that of growing mushrooms, is an intense and carefully tuned process.

First, Kiat collects mycelium samples from the wild and clones them in petri dishes in his lab. Once the mycelium starts to run cleanly, the cultures are then used to inoculate a container full of millet, where the web-like mycelium colonises the grain. Finally, the colonies are transferred to even larger bags of sawdust and wood chips, from which mushrooms start to fruit.

This is work that requires precision. One false move could contaminate the entire batch and undo weeks of work. So it’s strange, then, that Kiat would prefer to call himself an artist and his lab, a ‘mushroom design studio.’ Looking around, I can see examples of his artwork: unsettling sculptures of mushrooms growing out of replica human skulls and lamps with protruding mushrooms hanging from the ceiling.

“Growing mushrooms is as much about feel and intuition as getting the measurements right,” Kiat explains. “Fungi are fickle organisms. I know some scientists who can’t fruit mushrooms to save their life—even when they follow a fixed formula. On the other hand, some artists can grow mushrooms with one eye closed.”

This kind of intuition has been honed through over a decade of experience. Before starting Bewilder, Kiat worked on a local farm, where he cultivated mushrooms from waste substrates by converting two disused toilets into his personal R&D lab.

“I moved into the men’s toilet and covered the entire room with duct tape and plastic sheets,” he recalls wistfully. “The samples I kept in the urinal. It was terrible because there was no ventilation in there. I had to step out every half hour just to get fresh air.”

These years of experimentation and play have made Kiat who he is today. Three years ago, the farm shut down and all of his cultures—a two-door fridge filled with them—were thrown away, leaving him to start from scratch again. For many, this would be a failure, but to Kiat, it held the promise of a blank canvas. Now in his early 40s, he no longer feels insecure about calling himself an artist.

“Looking back, I wouldn’t exactly call it an illustrious career,” says Kiat. “I guess I always had a rebellious streak. A bit stubborn. I don’t really fit the mold of your typical Singaporean.”

Despite his personal passion, mushrooms are only a means to an end. Kiat’s primary goal is to educate the Singaporean public on the environment. As a business, Bewilder is structured like the mushrooms he grows: there’s an education component, where Kiat holds mushroom workshops with the public. The second spore is the R&D that goes into creating sustainable materials using fungi, a technology that could one day replace materials like styrofoam. Finally, there’s the F&B component, where he plans to supply top-quality mushrooms to high-end restaurants.

“Right now I’m in the colonising period,” says Kiat. “On one hand, it’s tough to do this because no one else in Singapore does it. It’s just me. But that’s cool. I get to play around. I get to shake things up. People in Singapore aren’t used to seeing this kind of stuff, so straight away, it attracts attention.”

Ultimately, Kiat wants people to be more eco-literate at a younger age, to understand that we are all part of something that’s bigger than ourselves.

How Singaporeans Treat Nature

A tree falling in the forest is a momentous event.

It provides much needed sunlight for saplings on the forest floor to grow. The trunk of the fallen tree becomes home to insects and fungi. As the tree decomposes, it becomes fertile soil for the next generation of life.

But in Singapore, who shows up first? The saplings and fungi? Or does NParks show up with a team to remove this ‘dangerous obstacle’?

“Singapore sells a pretty picture of green spaces and people living in harmony with nature,” said Kiat.

“A part of this is true. We’ve done a great job at putting greenery all around us. But do we really live in it? I don’t think so. When you look at parents and their kids at our crowded parks, it’s almost as if they don’t know how to interact freely with the natural world.”

Garden City is both window-dressing and a clever marketing campaign for tourists. In reality, when a tree grows out of line in Singapore, we trim it. When there’s a hole, we fill it. Every bump in the road is smoothed over. Every risk and uncertainty is made more predictable.

We plant non-native trees along the roadside and are surprised when the roots don’t run deep and end up falling over.

But it wasn’t always this way. Singaporeans are just two generations removed from people who still know the names and uses of certain native plants and fungi. These traditions are kept alive in the makciks who still forage on Pulau Ubin today, and the villagers in remote corners of Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, these are largely oral traditions. They are not documented anywhere. In another generation, Singaporeans will become tourists in their own land.

“That’s what I feel angry about. In Singapore, it’s all about producing results,” says Kiat. “What’s the yield of this land? How much money can this make? When will it be ready to be consumed?“

“But hey, slow down, you know? Let’s try to understand the land we live on first, instead of thinking that we already know everything. That it’s all just there for our benefit. It’s so arrogant to think that way!”

If there’s one silver lining to this pandemic, it’s the kick in everyone’s ass. We’ve been forced to slow down and confront the sometimes uncomfortable things about ourselves. It’s making us question the important things in life.

“Don’t get me wrong,” says Kiat. “Making money is important but it’s not the most important thing in the world.”

“Ultimately, we as human beings are the biggest problems on the planet. We are the cancer. So we need to find ways to keep ourselves in check.”

“Besides that, I don’t have any easy answers.”

Please, Accept the Mystery

“I fell in love with mushrooms because they both scare and excite me,” says Kiat.

”When a fungi sample gets contaminated in my lab, it freaks me out too, okay? There are some molds that are so vile and toxic it’s almost too repulsive when you’re confronted with it. But at the same time it’s a push and pull thing. Why am I so repulsed by something so natural? It makes me want to understand it even more. That’s the contradiction. Everything in life is ultimately that lah.”

This attitude of curiosity and exploration feels out of place here.

There’s this tendency in Singapore to put people and things into boxes. You’re an artist. She’s a scientist. You belong in this box. She belongs in hers. This is the yield the land can generate and this is the economic value you can create. The line ends here. No trespassing.

We rush to make ourselves useful without taking the time to truly come to terms with who we are and what we actually want.

As a result, Singapore’s brand of resilience is a fragile and stage-managed one. The constant interference with Nature and in people’s lives stunts their ability to innovate and adapt. It creates comfort without intimacy, safety without connection.

The roots run too shallow and the soil lacks the essential nutrients of life.

We’ve become disconnected from the land we live in and our memory and knowledge of it is fading faster than the forests are disappearing.

But if Covid has taught us anything, it’s that there’s no hiding from the uncertainty of the world. As the saying goes, life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.

There’s also no running away from ourselves.

“This is the way I see the world,” says Kiat. “There’s good stuff and bad stuff in it, but there’s no true good or evil. It’s all just one big mishmash of everything that’s constantly moving and changing.”

As human beings, we have to remember that we’re part of this evolving mystery too.

Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.