Photography by Liang Jin Tey unless otherwise stated

I’m sitting on a 12-seater speedboat, seawater splashing lightly onto my facemask as the Yamaha outboard motor hurtles us in the direction of Changi Ferry Point Terminal.

About a kilometre before reaching the pier, our boatman slows down and puts the engine on idle. I don’t even shift, budge or ask what’s wrong. After spending five days out at sea, I know that our small watercraft can’t just plough through the series of strong waves that the boatman spotted swelling towards us—we’d all tumble out, or at the very least, get thoroughly soaked. We waited for the waves to pass underneath before making our way to the mainland.

Admittedly, there had been a slight sense of romanticism and a considerable chunk of cheekiness when I pitched this assignment. What a fish out of water tale it’d be, I laughed (no-one else did). Joke’s on me, though — I was booted out of the office to spend a week at a modern floating fish farm. Return with a first-hand account of the farm-to-table process, they said.

I now know that it takes about eight months for Asian sea bass to grow from tiny fry to an adult that’s ready for harvesting. I now know that even if you grip an adult Asian sea bass tightly, it could still wriggle out of and/or pierce through your gloves with its sharp gill plates and spiny top fins. I now know that there’s a particular artery nestled within its gills that you need to sever and bleed out—this kills the fish quickly and produces tastier blood-free fillets. I now know the optimal storage temperature of frozen fish (about -19°C).

I also know that the smell of fish on your hands doesn’t go away for at least three days.

These lessons were gleaned from a stint on a floating fish farm located two kilometres off Changi Point Ferry Terminal. More specifically: I voluntarily worked as a farmhand on board the Eco-Ark, a rectangular floating platform that arrived in Singapore waters in October 2019. Location-wise, it’s taking up 1,400 sqm of sea-space near Pulau Ubin’s coast – about a quarter of the size of a football field.

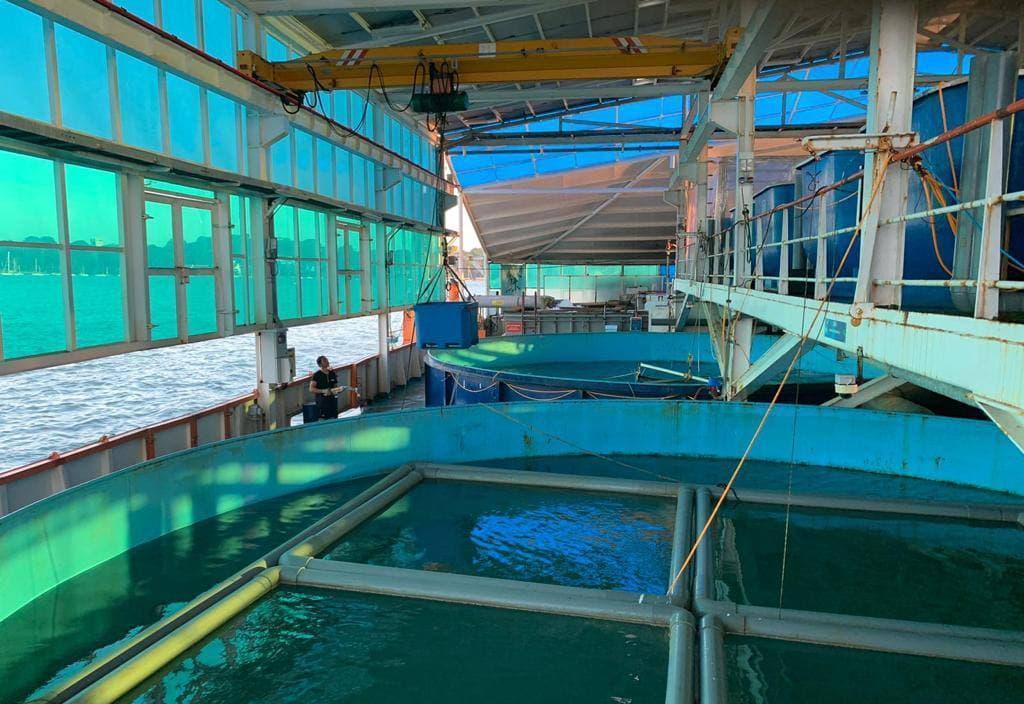

Accessible only by direct ferry, this was where I spent my 9-to-6 job placement for five days. Think of the facility as a high-tech farm that produces hybrid groupers, Asian sea bass and red snappers. The high-tech parts are primarily located at the front of the Eco-Ark, where industrial-sized pumps draw in seawater and filter and remove solid waste. The facility also generates its own ozone — a gas that smells like thunderstorms — to sterilise the seawater.

The resulting filtered sterilised seawater only then enters the culture tanks for Eco-Ark’s fish to live in, explained Lai Yongyi, the farm operations manager (and my temporary boss). The usually soft-spoken man, lean but sinewy from over 15 years of fish farming experience, had to speak much louder over the motorised din of the massive spinning pumps. Considering the sensitive moving parts and the crucial role in the entire operation, I’m not allowed to linger around here. Nobody is, unless they’re maintaining the pumps.

I soon got used to tuning the noise out after a couple of days on board the Eco-Ark. Worries of acquiring a harsh suntan and shaky sea legs dissipated just as quickly. The platform is entirely covered, shielded from the elements that would have rapidly baked and soaked all of us.

Solar panels line the roof, producing self-sustainable electricity to run the whole shebang. The floating platform’s foundation is spudded into the sea bed, so we’re not wobbling around. Even for a landlubber like me, the rocking sensation is just about slight.

The farm found its footing during a turbulent time. February 2020 saw the company, Aquaculture Centre of Excellence (ACE), make its first-ever harvest of fish on the Eco-Ark right before the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Much later on in November, the facility added a nursery and a post-harvesting unit, establishing a complete fish farming ecosystem. Essentially, a fish will undergo its entire life cycle from larvae to adult on the Eco-Ark before it gets harvested, killed, gutted, cleaned and packed for sale.

ACE CEO Leow Ban Tat is a firm believer in having tight control over the whole farm-to-table process. He’s happy to tout that ACE is the only company in Singapore to process its own fish—other farms outsource the processing services to a third party. More control over the whole process would mean that ACE could ensure the quality of fish stays tip-top, from the moment the fish wriggles out of its egg sac to the moment it gets sealed in vacuum packaging.

My journey from bungling writer to fumbling farmer began in Eco-Ark’s hatchery, a small, sealed-off section on the upper deck. It’s terribly humid, snug and sticky inside, but that’s by design, said Mr Lai. The environment must be kept at a constant warm temperature to ensure optimal survival conditions for the wee fish babies swimming about in the hatchery’s eight huge tubs. It gets cold out at sea at night.

Spawned from eggs purchased from the Singapore Food Agency (and neighbouring farming partners), the newly hatched young fish are minuscule, barely the size of a fingernail. Tossing tiny granules of feed over the surface of the water, Mr Lai tells me that there are up to 40,000 fish in each tub. He chuckled at my astonishment, explaining that not all of them will survive. But the survival rate here is a heck of a lot better odds than fish out in the wild.

I had the task of grading the baby fishes. This involved separating them according to sizes, splitting the big ones from the small ones to prevent the former from gobbling up the latter. Cannibalism is rampant, even among fish as young as these. But considering the tens of thousands of fish in one tank alone, how does one even begin to set the sizes apart? We used a highly advanced fish grading tool that people in the culinary circle would refer to as… a colander.

“Gentle, gentle,” cautioned Mr Lai as I swished the metal sieve around in the water to get the smaller fries to swim out of the 1.2-inch holes. Clockwise, anti-clockwise, up, down. Slowly, the tiny, fragile critters that were small enough to squeeze out of the perforations wriggled free into the waters. We released the remaining big lads into a different tub, where they can’t commit fratricide on the weaker siblings.

Meanwhile, Aung Kyaw Min — an ever-smiling farm assistant with abs for days — was occupied with scrubbing an empty nursery tub. Hygiene is crucial at this stage of the fish’s lives, said Mr Lai. The tubs and filters need to be cleaned of all the gunk once every three days, and with 40,000 fishes excreting waste in each one, you can imagine the accumulated filth.

I now know as well that when fish make it past the fry stage by developing scales and fins, they’re called juveniles. Nothing to do with delinquency though, that’s just the correct term. Once they’re about the length of a finger, the fishes graduate to the larger tanks in the nursery in the open air, no longer in musty conditions. Here was where they’d stay for months before getting transferred to the four gigantic main tanks sitting in the main deck below the nursery to grow to adulthood.

“You wouldn’t want to swim in there, man,” Ben Pang pointed at the massive, swirling tanks below.

Ben, a strapping bespectacled fellow farmhand, was just as new to the Eco-Ark as I was—the 24-year-old student had started his ACE internship a week before. It was part of his search for work experience related to his Bachelor of Science degree at James Cook University, where he’s the only student in his batch majoring in aquaculture technology. I had thought that he was a fish farming veteran the first day I came on board—he was completely covered in fish blood and scales when we first shook hands.

“Why not?”

“See all that foam and black clots?” Ben pointed at the dark, bubbly sludge spinning in the middle of the tank. “That’s from all their poop and pee.”

Though the youngest personnel on the Eco-Ark, Ben turned out to be pretty damn knowledgeable about the fish farm’s inner workings and processes and the fish that populate it.

“I guess fish saved my life,” he pondered out loud during one of our lunch breaks on an empty bumboat facing Pulau Ubin.

Having suffered from depression since he was 12-years-old, what helped keep him alive were his pet fishes: feeding them and maintaining his aquarium centred him to the path towards recovery.

It was his interest in fishing and marine life that eventually drove him to study aquaculture.

“After reflecting on it, I thought that I might as well make something out of my interest,” Ben offered. He found some additional merits to the first-hand experience working at the farm: he lost about 4kg after his first week at Eco-Ark.

Which reminds me. Despite the facility being a relatively high-tech one — with monitors to measure oxygen, ammonia and temperature in the tanks, as well as automatic feed distributors — modern fish farming still requires a decent chunk of manual labour.

Case in point: fish harvesting. ACE had just acquired a dazzling piece of industrial engineering called a fish pump, capable of sucking up live fish from one tank and transferring them into another. Essentially, the Asian sea bass gets sucked into the fish pump and gets catapulted out from the exit trough, confused but unharmed.

“It’s beautiful,” Mr Lai said out loud to no one in particular, as he watched the fishes shoot out of the tube.

The four main tanks holding the farm’s adult Asian sea bass and grouper fish go deep. Way deep. One would have to go down below decks to get a glimpse of the fishes through a glass window. Watching the fish popping in and out of view, Ben described how each of the tanks has been specially designed to maintain a continuous vortex to mimic sea currents instead of letting the water stay stagnant. Asian sea bass tends to swim against currents, and the constant exercise would mean that the fish would grow leaner and longer, which makes for nutritious meat.

Nick Goh, the senior aquaculturist on hand at Eco-Ark, added that the clean filtered seawater would mean that they could keep everything organic. No antibiotics needed to be fed for the fish to fight off infections. No vaccinations required during the juvenile stage. And certainly no growth hormones involved.

It’s difficult to pin down the 27-year-old aquaculture major to any one spot. His daily workflow sees him zipping to and fro different sections across the entire facility, checking on fish health and production rates.

On the fourth day, however, he needed Ben and I to enter one of the tanks and drive the hundreds of fish into a net for easier harvesting. But first, we had to pump out the water and climb down the ladder.

I didn’t even have to time be afraid of heights. Or perhaps it helped that I didn’t look down during the descent, with only a rope to hold on to. While I managed to drop to the bottom just fine (after minutes of awkward clambering), I realised that I really shouldn’t get any of the remaining waste-filled water anywhere near my eyes and mouth. I was waist-deep in the water, struggling to move among the swarm of sea bass darting around and in between my legs.

Together with three more farmhands, we managed to secure all the fish into a single net. Pro tip: wear some sturdy gloves if you ever find yourself hauling up a net filled with lots of fish one day. You don’t want to get cuts and bruises from the wet nylon and the struggling fishes.

Speaking of gloves, you’ll need them if you, like me, need to kill and bleed out 50 wriggling sea bass at one go.

There was a day when we hauled up over 327 kilograms of fish for harvesting, and all of them needed to be bled out quickly. It was here that I learned promptly that there is no escape from getting fish pee on my clothes during a slaughtering session.

The experience is best described like this: Attempt to pick up fish. Fish wriggles out of my hand and flops back into the tub, sending up muck and blood onto my face. Pick up fish again. Fish shoots a stream of urine at me. Grip the fish harder. Drive shears into its gills. Snip. Check if blood is flowing out. Toss bleeding fish into another tub of ozonated ice water. Repeat.

“If you’re sensitive, it helps if you don’t look at their eyes,” suggested Ben. The other farmhands didn’t even blink—they were snipping and bleeding out the fish (with bare hands) at the rate of 8 fish a minute.

Time is crucial when it comes to freshness. As soon as the fishes are killed, they are immediately sent to the post-harvesting facility — a refrigerated room where rubber boots are essential. The fish processing is handled by two young Vietnamese dudes, both of whom only speak a smattering of English.

One person descales and guts the fish, while the other power-washes the fish down and tosses it in iced water. Typically they’d do the vacuum packing as well, but since Ben and I were on hand, we would handle it.

We would stuff the fishes in special plastic bags and use the industrial vacuum sealing machines to pack each of them nice and tight. Vacuum packing the fish prevents them from spoiling easily too, with none of that fishy smell. All of them would be separated by weight class before going straight into cold storage or delivered chilled to ACE’s customers.

It’s mainly business-to-business sales for the company right now, says Joie Lee, the General Manager for ACE’s business development side of things. The bulk of customers are made up of wholesalers, resellers and restaurants. Interestingly enough, local Thai restaurants really love getting supplies from Eco-Ark—the locally farmed sea bass make for great Thai-style steamed fish with chilli, lime and garlic. According to her, the luxe kitchens of W Hotel and Tung Lok Restaurant are supplied with fresh Eco-Ark fish as well.

Of course, the company would love to have regular folks buying their fish direct from ACE. Joie shared that on top of their own online fish market, the freshly-farmed fish is also available for purchase from Redmart.

This, on top of upcoming plans to sell their produce at NTUC FairPrice. Making their locally-farmed fish available for purchase is one thing, but getting locals to buy them is another. Joie admitted that the fish from Eco-Ark are priced a tad bit higher than imported ones.

“We need to put ourselves in the customer’s shoes and figure out why they would want to pay a little bit more,” she explained. “In the end, it’s all about just how fresh and safe our produce can be.”

Joie points out that the distance and time taken from Eco-Ark to mainland Singapore is much shorter than the stretch between overseas farms and markets here. With all the transportation, clearance at customs, and finally reaching distributors, it would take much longer for imported fish to make it from farm to table.

She rightfully points out that I should already know after working on the Eco-Ark for a week that sheer freshness is the key differentiation point.

And it truly is. I have killed a batch of 30 fishes at one go. I have seen them degutted and cleaned within an hour. I have personally vacuum-packed each of them. I have stored them in a styrofoam box filled with shaved ice-flakes. I have carried that same box on a ferry and transferred it onto a waiting freezer truck. I have seen the truck head off to a hotel, where its kitchen awaits the fresh catch. I have cooked a locally-farmed sea bass direct from the farm. And I know now that it tastes exceptional.

But would I consider leaving it all behind and become a full-fledged farmer? Perhaps. Millennial burnout is absolutely real. I can’t really remember the last time my brain wasn’t hyper-alert about to-do lists, deadlines, emails and other errands. For those five days on the fish farm, though? Things did get physically taxing at times, but at least chronic stress wasn’t around. Getting away from the city’s hustle and bustle does wonders for the soul, too, as Ben would attest. It’s a legitimately viable career option for millennials, is all I’m saying.

Idyllic views of the Pulau Ubin coastline helped, of course. As we watched the sun set on the horizon at the end of a solid day’s work, Nick expressed his hope that more people his age would want to join the aquaculture industry.

“We need more young blood,” he says. “We need people to continue ensuring our oceans stay sustainable and our people stay fed.”

This article is brought to you by Singapore Food Agency.

If you haven’t already, keep up with us on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.

Think you could survive a week as a fish farmer too? Fish for compliments at community@ricemedia.co.