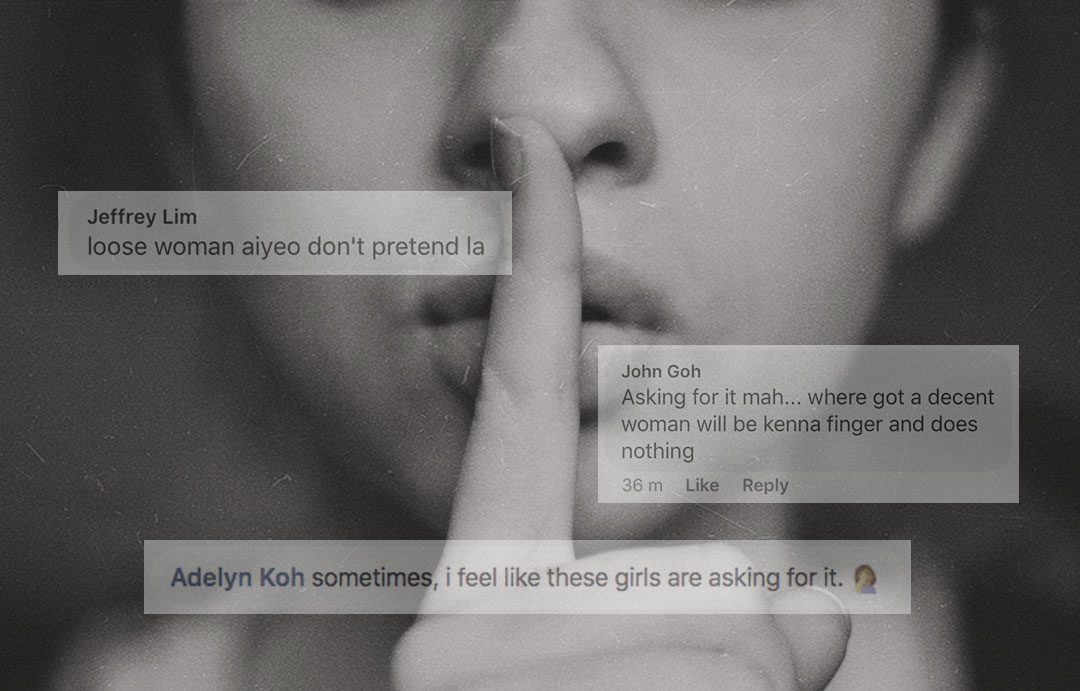

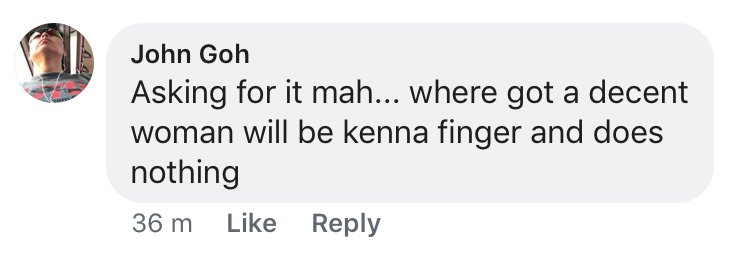

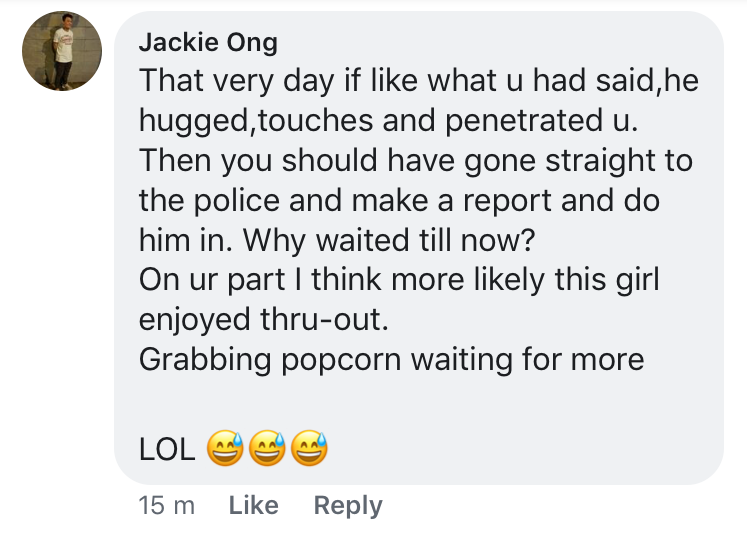

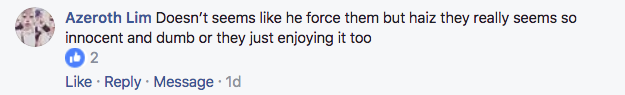

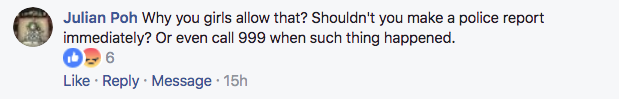

When our Eden Ang story broke on Monday, 26 February, many of the reactions placed blame on the women mentioned in our story, especially Dawn, for landing themselves in their respective circumstances. Apparently, the women had “no one to blame but themselves”.

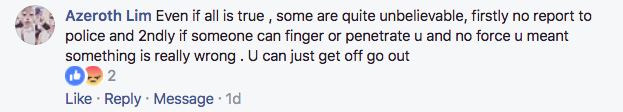

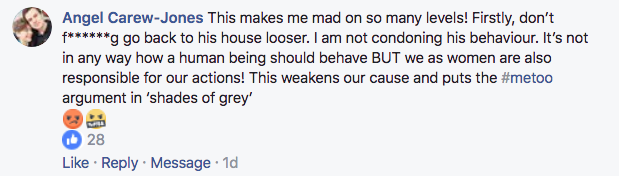

With Dawn, many questioned why she had allegedly continued to go back to Eden’s house time and again, even though she felt uncomfortable the first time. It was like “putting your head in the lion’s mouth hoping it won’t snap shut”, as one analogy described.

One of the commenters, Angel Carew-Jones, who appears to be a woman, said, “Firstly, don’t f*****g go back to his house looser [sic]. I am not condoning his behaviour. It’s not in any way how a human being should behave BUT we as women are also responsible for our actions! This weakens our cause and puts the #metoo argument in ‘shades of grey’.”

The reactions from the public reflect that we are neither mature enough to handle discourse that deals with grey areas, nor empathetic enough to imagine ourselves in situations we cannot fathom having to go through ourselves.

While many have argued that women have a right to say ‘no’, or to report any non-consensual activity, this reasoning neglects the personal guilt and shame women often experience.

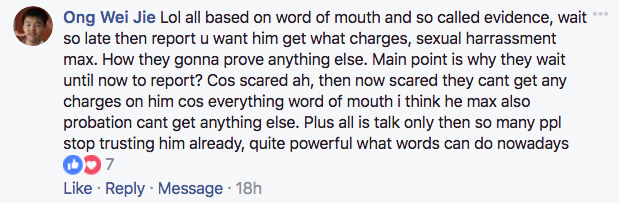

For example, reporting sexual harassment and/or assault is a complex process that doesn’t simply involve walking into a police station and signing a form. It requires survivors to relive their trauma over and over again in station interviews, and possibly even in court, with no guarantee that justice will be served.

On top of that, survivors are also heavily scrutinised by the court of public opinion, should they choose to bravely come forward on social media. This just makes it difficult to carry on with any semblance of a normal life.

As a result, many convince themselves that what happened was their fault, and that they may have inadvertently given consent. Women in general internalise the notion that their experiences would not be valid, and reason that it’d be better to stay silent than to speak up and get judged for doing the ‘right’ thing.

While many survivors do believe that they could have done something to prevent their situation from happening, it’s important to understand the main reason they don’t. When faced with perceived danger, it’s easier to act like nothing’s wrong to remain on the perpetrator’s good side. Instead of fighting, staying (and in some cases, going back to the perpetrator) is a mode of survival for these women.

So it’s easy to say these women should be courageous, that they should not have been so stupid to return to the house of someone who has already hurt them, and that they should have reported their harassment and/or assault immediately.

But true fear is all-consuming and paralysing, blinding one to alternative options. Often, men use their power to prey upon vulnerable women, who relent out of fear for what could happen to their lives, should they refuse to comply. These include instances of emotional manipulation, grooming, and even outright coercion.

These situations require men to listen, and resist making the situation about themselves.

Likewise, these situations also implore women who have never been in similar ones, because they’re somehow always able to say no or never feel forced, to listen to fellow women. Just because one has no problem with expressing consent doesn’t mean everyone else is the same.

For many people who are unwilling or unable to empathise, their reference point becomes what they think they would have done in that situation. So when they picture themselves in the position that the women were in, they imagine that they would have just walked away. In their own minds, they are terrified by the idea that they could be powerless.

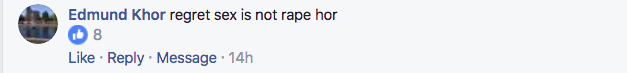

But let’s be clear about one thing: things can happen without explicit and full consent being given and/or understood prior. When one party wants something more than another, they’re usually more focused on getting it than ensuring the other party wants it the same.

Another rule to understand is that any party engaged in a consensual sexual activity is allowed to change their mind at any time. To choose not to listen to this refusal is to commit sexual assault or harassment.

In any case, the core issue has always been this: no matter how unwise or unclear one’s actions, no one deserves or “asks” to be sexually harassed and/or assaulted. A woman chooses to go to someone’s house; she does not choose to be raped.

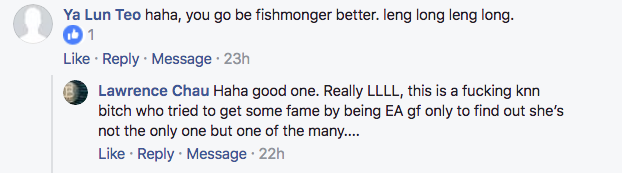

Unhelpful and unsympathetic reactions only aggravate the situation, by reinforcing victims’ self-blame and making them regret their decision to speak up, simultaneously compelling future victims to stay silent.

Then I recalled the Harvey Weinstein case. Admittedly, this happened in the US, but the women who spoke up against Weinstein, a powerful Hollywood mogul, also cited being terrified of losing their jobs, reputation, and in some cases, their lives. Their fear echoed that of friends and acquaintances of mine who have been sexually harassed and/or assaulted.

In other words, the culture of fear around speaking up about sexual harassment and/or assault is the same around the world. Hence I thought there might be value in pursuing this story to see what I could find.

That said, reactions to our first part of the Eden Ang story have not been the only frustrating thing about this entire process.

I forgot this was Singapore, where social circles run small and courage even smaller. Not only is the whistleblowing culture frowned upon in Asian societies, almost everyone (both men and women) I approached was afraid of damaging their own reputation by speaking out.

Most noticeably, however, were those in positions of power within the entertainment industry who were seemingly complicit in the culture of sexual harassment. They clearly had influence, yet chose to remain silent, because they were more interested in protecting their interests.

They were so terrified of being named or even remotely tied to this story that they touted apparent non-disclosure agreements they had signed as a reason to maintain their distance. While insisting that they cared for these girls and wanted to ‘expose’ the dirty deeds in the industry, they also made it clear they did not want their names associated with the entire process.

Behaviour like this can be deeply counterproductive for journalists. I was regularly frustrated by their simultaneous desire to help and their exaggerated paranoia of what could happen to their own lives.

With this story, there were girls keen to share their allegations publicly, but only under the cloak of anonymity. Anonymity is tricky: many argue that anonymous sources negate the credibility that is crucial in any robust journalistic endeavour.

Furthermore, a source’s need for anonymity might affect the level of trust between them and the journalist.

I would ask survivors if Eden had any ‘dirt’ on them that he could leverage as a reason for them to ‘ruin’ him. I had to put their allegations through rigorous, yet sensitive and tactful, questioning that I’m well-aware might have forced them to revisit a traumatic past.

In them, I also recognised the universal behaviour of women downplaying our own feelings or experiences, and occasionally even convincing ourselves we don’t deserve to feel the way we do, when we feel ‘threatened’ by a man’s social influence. (You don’t have to be a victim of sexual harassment and/or assault to know how this feels.)

Nonetheless, I was determined not to take away these women’s right to tell their stories. I constantly made sure they felt comfortable sharing these allegations, and informed them that they could withdraw participation at any moment. I wanted these survivors to come out in their own time, if at all.

It didn’t help that just at the end of 2017, two New York Times reporters, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, broke the Harvey Weinstein scandal. Shortly after, Ronan Farrow reported on Harvey Weinstein’s army of spies for The New Yorker. These two monumental reports significantly changed the conversation around sexual harassment and/or assault and set an unspoken standard for all future articles calling out similar instances.

The pressure, both external and self-inflicted, was suffocating.

And yet, after Facebook user Kuroe Kun first wrote the Facebook post about her friend allegedly being sexually harassed by Eden, I realised no one had apparently attempted to dig deeper to put together a full story.

What bothered me even more was the tendency for those who defended Eden not to believe Lilith (Kuroe Kun’s initially anonymous friend and the first survivor who came forward) and to insist that the alleged harassment was her fault.

As a society, we are now in a time when we’re obligated to support women. If we are committed to making this world safer for women (including our friends, family, and children), then our first response to women sharing testimonies of sexual harassment and/or assault cannot be skepticism.

That’s not to say we immediately side with them, but it does mean our first instinct isn’t to dismiss or ridicule their allegations.

No doubt, all of this is nothing compared to the loneliness actual survivors face. The responsibility on a journalist is further exacerbated by the need to do right by the survivors.

I don’t claim to speak on behalf of journalists, even those who share the misfortune of reporting on alleged sexual harassment and/or assault. But gratitude or appreciation is unnecessary.

Instead, it would be nice if we could, first and foremost, stop branding these women as victims. Call them survivors. Even better, I never want anyone to have to write another article like this.

I hope for people to fundamentally get rid of the mentality in their own lives that enables the culture of shame and fear around speaking up about sexual harassment and/or assault, as well as unlearn the harmful behaviours that normalise sexual harassment and/or assault in the first place. I would like survivors to feel comfortable coming forward in the future without fear for their lives, and for society to give them a fair hearing when they do.

I want us to be appalled and disgusted that sexual harassment and/or assault still happens without severe consequence in a supposedly first-world country.

And I want this anger to mean we never stop working towards significant, tangible, and lasting change.

Some of the opinions in this piece were based on the thoughtful comments of these readers on our Facebook post: Harry Sa, Huiwen Yeo, Sharul Channa, Visakan Veerasamy, and Kenneth Chen.

If you have experienced any form of sexual assault or harassment, please contact AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre at 6779 0282 or email them at sacc@aware.org.sg. More information can be found here.

Have something to say about this story? Drop our writer a note at grace@ricemedia.co.